Analysis

New GAVEL Calculator Demystifies Auction Prices and Premiums

Here's a helpful guide to auction premiums and hammer prices.

Here's a helpful guide to auction premiums and hammer prices.

Eileen Kinsella

Francis Bacon’s triptych “Three Studies of Lucian Freud” sold for a hammer price of $127 million at Christie’s New York in November 2013. The buyer’s premium added another $15.4 million for a final price of $142.4 million.

The hefty premiums that auction houses tack on to public sales is undoubtedly one of the most opaque and confusing aspects of the booming art market. Auction premiums change constantly and are anything but simple, applied as they are on a sliding scale (i.e. 25 percent on the first $100,000, 20 percent on the next $1.9 million, 12 percent on anything above $2 million). They were at the heart of the price fixing scandal that erupted in the late 1990s, which resulted in jail time for former Sotheby’s CEO Alfred Taubman, not to mention hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements and legal bills for both Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

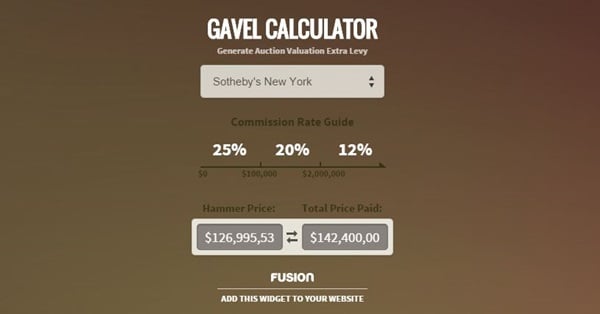

Now financial blogger Felix Salmon has rolled out an innovative and much-needed (not to mention free) new widget to address the premiums problem. Meet GAVEL (embedded below), the acronym for the auction price calculator he dreamed up that is available at Fusion.net, where he is a contributor. Despite its wonky acronym (Generate Auction Valuation Extra Levy) we predict it will be enthusiastically received by anyone who follows auction prices, including collectors who want to have a better idea of how much they’ll be shelling out in premiums before getting caught up in the moment.

As Salmon told artnet News, “You can find calculators on the Internet for just about anything, whether you are working out mortgage amortization or bond yields. You name it, you can calculate it. Because I write about art auctions a lot, it seemed like there was a gaping hole.” Earlier this year he tackled the wild world of sellers’ commissions in a revealing post for Reuters titled “Adventures in art-market commodification, enhanced hammer edition.”

Even more complicated than figuring out how much of a premium gets added to the hammer price is “working backwards to the hammer price.” “You read something in a press release and it’s impossible to find out what the hammer price is. It’s completely impossible so no one ever does it,” says Salmon.

Now it’s GAVEL to the rescue. Not only does the GAVEL calculator compute the premium based on the auction house, currency, and location of the sale, it also allows users to strip out the premium in order to go back and see the original hammer price.

Screenshot of the GAVEL calculator.

It remains to be seen whether or not knowing how much a work will cost with commission—down to the last penny—will have a chilling effect on bidding fever or serve as a deterrent to auction room battles. We asked veteran auctioneer and former Phillips CEO Simon de Pury what he thought of the new widget. De Pury replied: “You always try to work out in your head what the buyer’s premium is while you bid, but GAVEL will certainly help you avoid unpleasant surprises when you receive your invoice.”

The fact that auction house estimates do not include premiums is an issue that comes up over and over again when auction results are tallied and analyzed. New York Times writer Carol Vogel never fails to make this point on every major auction report she files on sales at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips each season.

Some observers argue that final prices are consequently inflated by premiums. Take for instance a work that is estimated at $80,000–100,000, but only gets as high as $70,000 in the bidding and sells anyway. On a hammer basis the work has fallen short of the minimum estimate by $10,000. But when premium is factored in, for instance for a major New York sale at Sotheby’s or Christie’s, the final price with premium for the same sale would be $87,500. In cases where the hammer is nearer to the high end of the estimate, the house can then claim the price exceeded expectations. The counter argument here is that the buyer is paying the entire sum anyway, so the part of the price that is made up by commission is irrelevant to how much he or she is willing to shell out.

Salmon thinks most people, even collectors, don’t realize the gap between what something gets hammered down for and the final price with premium. “When you look at the difference between these two numbers, there is this obvious hole. People don’t realize how much of a kind of tax there is. This makes it a bit more obvious,” says Salmon.

For instance, in 2012 when Edvard Munch’s The Scream, sold at a Sotheby’s New York auction for $119.9 million and briefly held the record for the most expensive work ever sold at auction, unless you were in the auction room when the hammer fell at $107 million, you would have no way of knowing that nearly $13 million of the price was comprised of the premium.

Salmon said the idea for the calculator had been “bubbling” in his head for a while and he finally found a willing development partner in Fusion.