Welcome to New Models, a series that highlights galleries innovating beyond the traditional ways of exhibiting and selling art in the primary market. From forward-thinking collaborative initiatives to novel uses of technology, the concepts it unpacks prove that there are more paths to success and sustainability as an art dealer than the default settings.

With galleries currently open and relatively lively in New York again, it can be easy to forget how barren and uncertain the city’s art landscape was in early spring 2020. Even before Governor Andrew Cuomo officially shut down all non-essential businesses in the state on March 20, a huge proportion of dealers had already voluntarily closed shop. Museums went into hibernation too, casting all sides of the New York art ecosystem into darkness. It was unclear whether dealers and artists could sustain their operations on remote sales alone, and no one knew when art lovers would be able to take solace or find escape by actually experiencing art in person again.

It was in this unsettled environment that gallerist Kate Werble confronted a high-stakes question: What could dealers and artists work toward together that wasn’t either a physical show or a digital experience? She realized the ideal answer would fill collectors’ IRL art void while also helping plug the fiscal hole she and her artists were suddenly facing.

Her solution was outside the box: a subscription plan for new, unique works by gallery artists, sold online and fulfilled on a rolling basis. Despite the idea’s unconventionality, Werble told Artnet News that the artists she approached with it “said ‘yes’ immediately.” The sales prospects were important, of course, but so too were the excitement of experimenting and the motivation to show up to the studio and create new work.

“We all wanted to have something to look forward to,” she explains. “The subscription plan was my answer to the digital moment that was happening.”

Seven months later, the concept is going strong even amid a revived gallery landscape—and pushing open the window a little further to an expanded vision of what art dealing could be.

Luke Stettner, To Be Invisible (2020). Courtesy of Kate Werble Gallery, New York.

How Does the Model Work?

Even before the silent spring of 2020, a growing number of sellers beyond the art world had already converted to the wisdom of subscription e-commerce. After all, why force your business to secure an endless string of one-off transactions with an ever-shifting consumer base in an uncertain market if you can lock in recurring revenue with a core group of faithfully committed clients?

According to consulting behemoth McKinsey & Co., top subscription-based retailers have amassed $2.6 billion in sales since 2016 thanks to the appetite for a steady stream of new clothing (Stitch Fix), make-at-home meals (Blue Apron), and male-grooming products (Dollar Shave Club), among others. Guaranteed monthly revenue has become so valuable this year that even traditional-retail giants like Walmart are getting in on the act.

A subscription plan for artworks is certainly different, but some of the same DNA and business logic carries over to the gallery sector.

Here in late October 2020, Werble offers three subscription groups that differ only by the artists involved. Each group includes three works—each by a different artist on the gallery’s roster—for an all-inclusive price of $2,000. (One caveat: delivery outside the US brings additional shipping costs.) The subscription price can be paid in full up front or broken out over four monthly installments of $500. Subscribers receive one piece every five-to-six weeks, with the third and final work promised within four months of subscribing.

Werble told Artnet News that she approached the nine artists now piloting the subscription with her for both logistical and aesthetic reasons. Seven have their studios in New York or the Berkshires, which was a vital consideration back when the global supply chain was in crisis; the other two, multidisciplinary artists Sofía Córdova and Luke Stettner, would contribute unframed photographs that they could print themselves and ship with no need for specialty art handlers. Werble also felt that strong themes connected each trio of artists, partly because they all knew and respected one another’s work, even if they were personally unacquainted.

Scarcity is a critical component of Werble’s subscriptions. Nearly all of the works available in the plans are unique, with the lone exceptions being Córdova’s inky black photos of found or dreamt objects. (Stettner’s grayscale text photos are all unique.) Werble also decided at the outset to offer only 45 subscriptions, meaning 15 for each group. In her mind, the choice differentiated her subscriptions from similar opportunities centered on editions (especially unlimited ones) that emerged during the shutdown.

“Editions are a great way to support institutions and artists, but we wanted this to be… more of a direct line to the artist’s studio,” Werble explains. “They made this for you.”

The result is much closer to commissioning the artists than simply ordering their pre-existing output. This helps foster the type of intimate connection forged between collectors, artists, and dealers during in-person gallery visits—and thus largely lost by the art market during the shutdown, no matter how many online viewing rooms cropped up. The personal touch even deepens on delivery, as Werble herself often drops off completed works with clients (masked up and socially distanced, of course).

To date, Werble’s calculations are paying off for everyone. Roughly 30 of the 45 available subscriptions were sold as of publication time, pending “a few” confirmations on Group C. The results are all the more encouraging since Werble only officially launched the program about a month ago. (Werble also found early proof of concept when she began “soft selling” the subscriptions to friends and family in the spring, including placing one of each subscription group way back on March 25.)

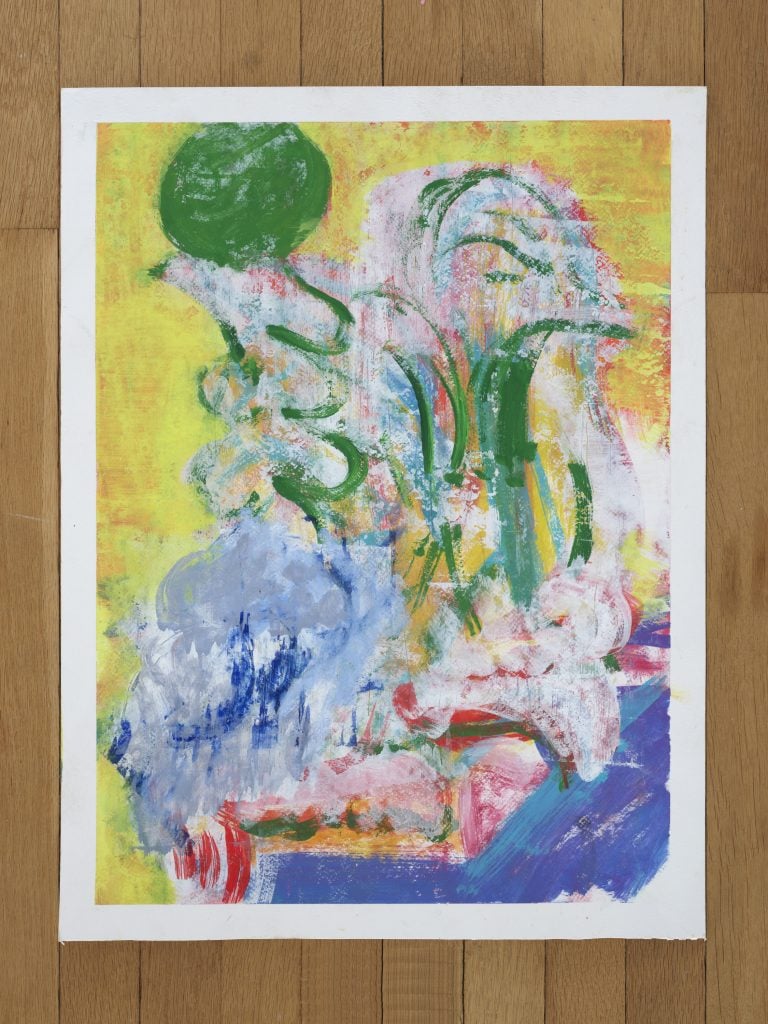

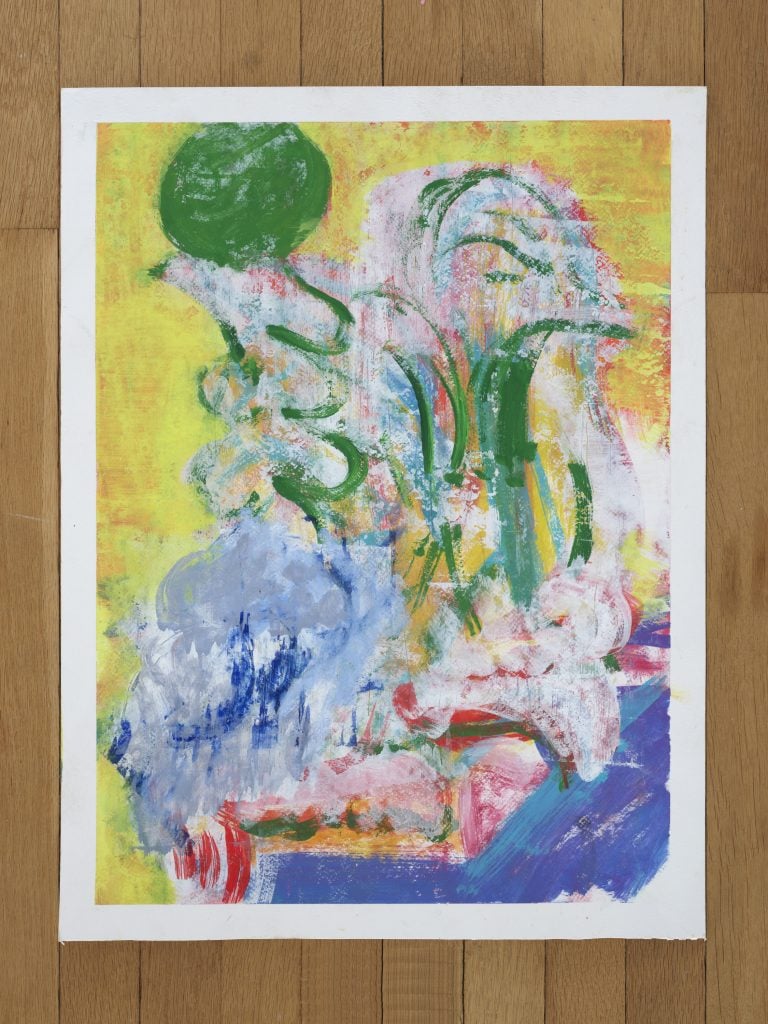

An example of a Michael Berryhill oil-on-paper drawing from the gallery’s Subscription Group B. Courtesy of Kate Werble Gallery, New York.

What Are the Other Benefits?

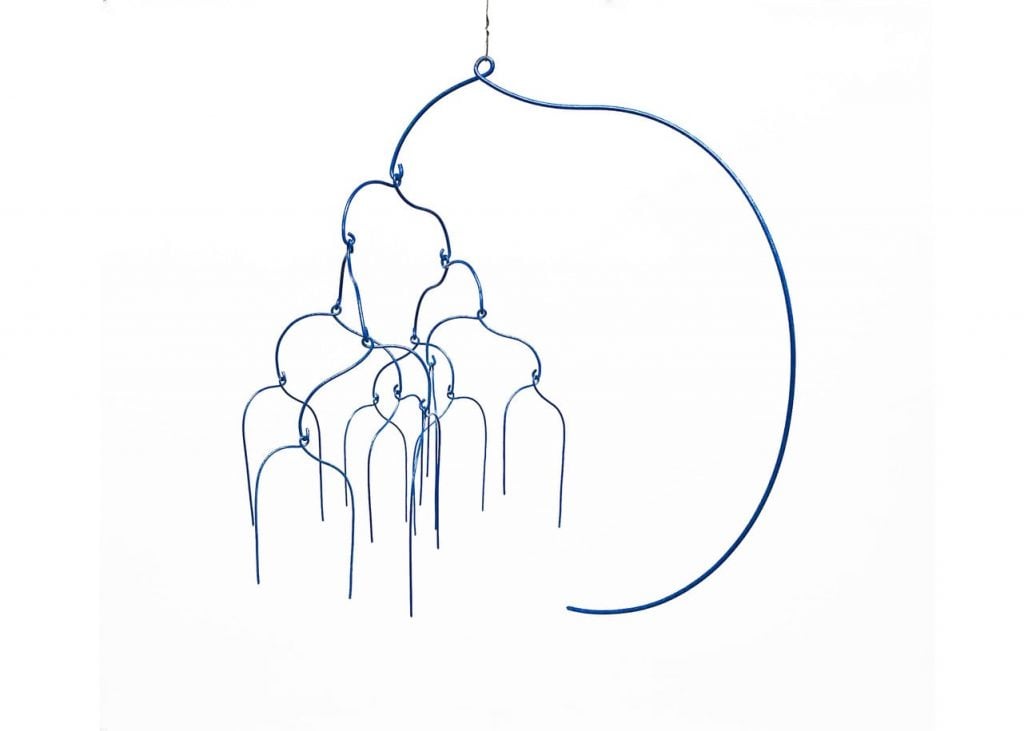

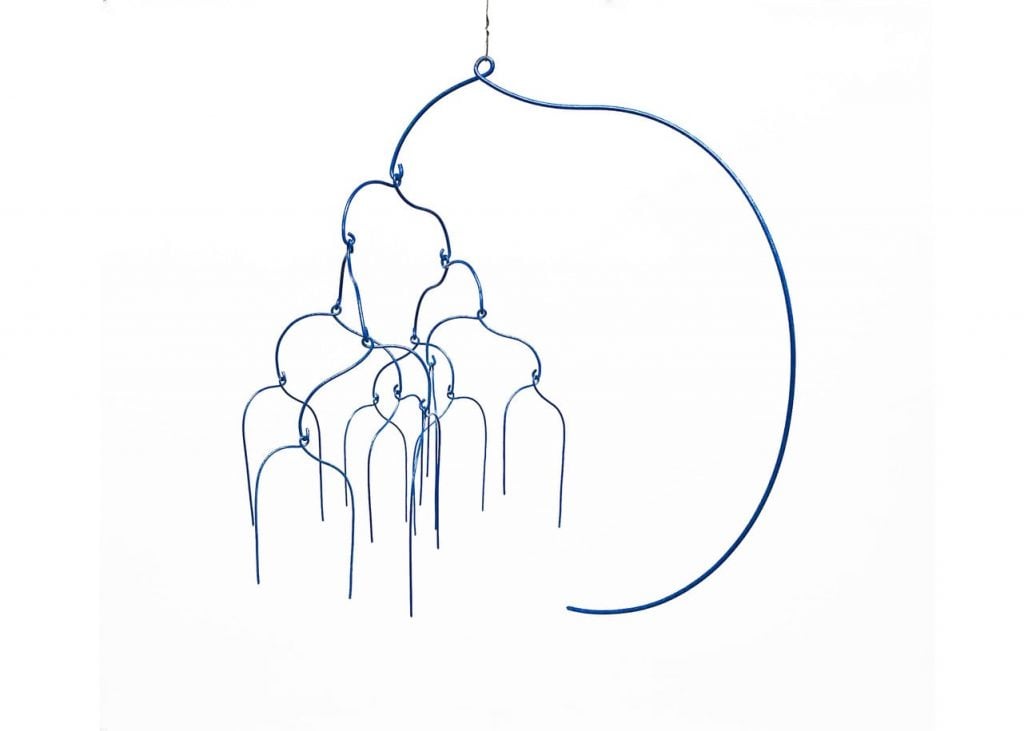

Although New York collectors now have plenty of options for in-person experiences with art, Werble’s subscription model provides value in other ways, too. One of those is monetary. Bought individually, every work available in the current plans would be priced higher than the roughly $667 clients pay for it by subscribing. For example, Werble relays that a single Michael Berryhill oilstick drawing like the kind included in Group B would normally be listed at $2,500, while a Beth Campbell mobile sculpture similar to the ones offered in Group A would be around $1,500.

Why discount the works so substantially, then? The answer is twofold. First, subscription pricing (at least for this pilot group) is a practical legacy of the lockdown. Werble arrived at the $2,000 figure and the 15-subscription cap in March by pro-rating what it would take to cover the participating artists’ studio costs in the event that life and business did not return to normal until July 2020. With so much uncertainty swirling, guaranteed sales revenue was worth a significant break on typical pricing.

The other reason involves a more benign (and arguably, exciting) brand of uncertainty. While the subscription groups indicate the general series or body of work each artist will work within, the specifics of the finalized piece are left up to the studio. A subscriber to Group B, for instance, would count on receiving a Berryhill drawing, but the subject, composition, and color palette would all involve an unknowable amount of variation.

Similarly, clients cannot mix and match artists into custom subscription groups of their own choosing. Again, Werble assembled the specific trios on offer in much the same way she would assemble a group show, synergizing the strengths and perspectives of the different individual creators into a greater whole. Ultimately, that is the mission of any dealer, and it would evaporate if collectors had the liberty to scan the gallery’s roster and pick out whichever three artists looked most appealing, as if they were concocting a lunch at Chipotle.

Beth Campbell, There Is No Such Thing as a Good Decision (Blue) (2020). Courtesy of Kate Werble Gallery, New York.

Summing Up and Looking Ahead

In total, then, Werble’s subscriptions ask potential clients to take a chance on the artists’ decision-making and the gallery’s curation, but they also dangle the carrots of a significantly discounted price and an established track record. Werble contextualizes these aspects of the model by noting that she is “trying to teach people to trust the artists” while simultaneously empowering them to “be surprised and expand their ideas about collecting art.”

The combination should be an especially enticing proposition to collectors in the early stages or with a strong interest in supporting emerging talent. Werble adds that subscribers have consistently felt rewarded for making the leap. “When the work arrives [with the collectors], I get these emails saying, ‘The colors are unbelievable!’ or ‘This is even better than I imagined it would be.’”

Based on the subscriptions’ early success, Werble is already gearing up to expand the model. She will launch a new subscription group in November, with an emphasis on photography and a portion of the gallery’s proceeds earmarked for charity. Over the long term, she intends on adding more subscriptions, including by working with artists who are not necessarily on the gallery’s roster.

However, she has no plans to give up her 12-year-old brick-and-mortar program yet. After moving out of her old space in the West Village in May, she reopened the gallery on East 73rd Street in late September with a new show of works by Berryhill. She has committed to the location until June 2021—enough time, she says, “to experiment with the space.” Given how her subscription experiment is going, it’s a destination worth watching.