As some of our clients have already learned, the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office has recently embarked on another of its periodic investigations into galleries and private art dealers—and their clients—in connection with possible violations of New York State and City sales tax regulations. (A press spokesperson in the DA’s office declined to comment when artnet News asked them to confirm this.) This short primer is the first of several articles on “Do’s and Don’ts” if you happen to get that dreaded phone call or subpoena from the DA.

But first, some background information. The last time the DA’s Office launched a similar large-scale effort in this area was in 2003. Many prominent galleries and art dealers were ensnared in that investigation, which resulted in numerous felony pleas and over $26 million in fines and tax restitution. To give you a sense of the penalties assessed, according to published reports at the time, Berry-Hill Galleries paid $750,000 in fines; Otto Naumann Ltd. paid $500,000; Bob P. Haboldt & Co. paid $400,000; the Chinese Porcelain Company paid $275,000; Art Advisory Services, Inc. paid $250,000; Macklowe Gallery paid $95,000; and S.J. Shrubsole paid $75,000, to name just a few. All apparently pled guilty to felonies.

There is no indication that the DA’s Office is going to be any less aggressive this time around. In fact, given the super-heated art market and the prominent role of some newly minted global players, the DA may even be looking to cast a wider net in its current investigations.

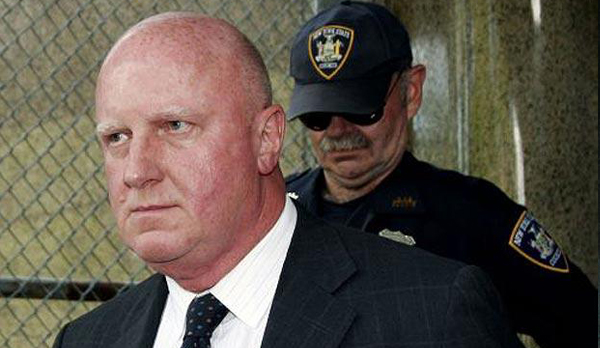

That’s good news for the City’s coffers (and some defense lawyers), but certainly not encouraging for those caught in the DA’s crosshairs. It is important to note, however, that in the past not all sales tax investigations resulted in either a fine or a criminal conviction—as some of our own relieved clients can attest. The difference between a successful outcome for you and a pair of handcuffs (or worse) is being proactive, having a thoughtful response system in place and following good professional advice.

With that in mind, here is what we would suggest if the DA’s investigator knocks on your door:

1. First, don’t panic—but, as importantly, don’t take this lightly. The DA is trying to build a case and will leave no shipping record unturned to uncover any wrongdoing. The subpoena you receive will likely require you to produce tons of correspondence and materials, will entail your spending dozens (if not hundreds) of hours in sifting through records, and will probably cost you tens of thousands of dollars in accounting and legal fees. And that’s a “good case” scenario. We will address “worst case” scenarios (e.g. the “plea bargain”) in a later article. The key here is to get to work on your response without delay. And if you think you may be a witness or a target in the future but haven’t yet been subpoenaed, make certain your records are in order now.

2. If you are approached by phone or in person, adopt a cooperative tone but indicate that you would feel comfortable speaking only with your attorney present. In some cases your lawyer will be able to obtain immunity for your statements but, importantly, you yourself will not be able to do so alone. Remember that the DA’s office and its crackerjack investigators are in the business of building criminal cases. Don’t even think about answering their questions without an experienced attorney by your side.

3. If you do receive a subpoena, take immediate steps to preserve all documents requested. Do not shred papers or delete anything from your system, tempted though you might be to destroy potentially incriminating evidence. Inform everybody in your company of this retention policy. It is very likely that the DA has other means by which to obtain this same information, and if the DA learns that documents or e-mails were previously in your possession and have now been willfully destroyed, you may end up being prosecuted for obstruction. As Martha Stewart learned, the cover-up is often worse than the crime.

4. Keep the circle as small as possible of those individuals who will be entrusted with retrieving and assembling the documents requested. Ideally, there should be one person—referred to as “the custodian of records”—who will be in charge of this task. Bear in mind that the custodian may be called upon to appear before a grand jury, or possibly even to testify at a trial about these documents. Accordingly, you don’t want a disgruntled hourly employee or temp worker in charge of this task.

5. Keep your communications in the workplace about the subpoena to a minimum. If you must discuss this matter amongst your associates in an email or other writing, be sure to copy your attorney. Doing so will generally (but not always) transform that writing into a privileged communication with your lawyer, shielding it from the eyes of law enforcement. And avoid any needlessly self-incriminating “mea culpa” e-mails. It is safest to assume that correspondence regarding the investigation with anyone other than your attorney will be read by the DA’s office and, possibly, used against you in court.

6. Do not discuss the subpoena with anyone outside of your workplace. If other parties are named in the subpoena, do not alert them to the issuance of the subpoena. You never know who may be cooperating with the DA and looking to cut a deal by providing incriminating evidence against you. Anything you say to that person will not be privileged and can be used against you. As anyone who has seen even one episode of “The Sopranos” can attest, when the going gets tough, friends turn on friends and family members turn on family members. Things can quickly turn ugly.

7. If you do come across documents or correspondence that you believe contain information that is of concern, be sure to flag them to your attorney. And keep in mind that not all documents need be disclosed in their entirety; a good attorney should be able to redact information that is beyond the scope of the subpoena, or is privileged, proprietary or irrelevant. You certainly don’t want to involve your clients in the investigation or disclose confidential information unless (and only to the minimum extent) absolutely necessary.

8. Finally, remember that a subpoena is only the first step in what may be a prolonged investigation. Even in the worst case scenario, a resolution could be years away—and strange things can happen during any investigation, both good and bad—which is why it is especially important that as few people as possible learn about the DA’s interest in your business. No one we know wants to be the poster child for sales tax evasion in tomorrow’s New York Post.

Next up: The DA wants to interview you in person. What to do?

Note: Because each situation is unique, nothing in this article is intended to provide the reader with specific legal advice. We would encourage anyone with a specific legal issue to contact his or her attorney directly.

Thomas C. Danziger, Esq. is Managing Partner in the firm of Danziger, Danziger, & Muro, LLP, which specializes in art law. Georges G. Lederman, Esq. spent 10 years in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office before becoming of counsel to Danziger, Danziger & Muro, LLP, where he specializes in white collar crime and art law litigation.

For more artnet News coverage of art law, see On the Case: The Real Deal on Authenticity and Sometimes It’s Not Too Late To Recover Your Art.