The art world has a money laundering problem. Last summer, a Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations (PSI) report highlighted just how bad the problem is, calling the art industry “the largest, legal unregulated industry in the United States.” Now, the explosion of interest in NFTs could be making matters worse—maybe much worse.

I like to compare buying and selling NFTs to buying and selling high art in a freeport, the tax-free, extra-territorial storage spaces where ultra-rich collectors stash their treasures. In both cases, parties exchange title, while no physical object needs to change hands. The art is the justification for the movement of a large amount of money.

Art’s subjective value and the art world’s obsession with secrecy and anonymity—the fact that you don’t always know who is behind these big deals—makes the art trade a honey pot for launderers.

Here’s the difference: With a freeport, there still has to be some kind of physical object in play, which means paying expensive storage fees and dealing with increasing government scrutiny on the space. In 2019, the European Parliament recommended as “urgent” the phasing out of freeports because of their use in tax avoidance, money laundering, and the secreting away of alternative assets.

Enter NFTs. Almost anyone can mint an NFT, at minimal cost, and they have exploded in popularity far faster than regulators have kept up. With the shocking amounts of money now being paid for NFTs at auction, the space has to be a tempting one for bad actors.

Representation of cryptocurrencies and non-fungible token. (Photo by Jakub Porzycki/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

Trade-Based Money Laundering

The most practical way to launder money with NFTs would be via what is called trade-based money laundering (TBML): deals that appear legit on the face, but are meant to hide the flow of ill-gotten gains.

TBML can take several forms, explains Jesse Spiro, head of policy initiatives at Chainalysis, a blockchain analytics company. The most common is over or under invoicing. “All you ostensibly need is two parties that are willing to engage in a transaction for an NFT to make that work successfully,” he said.

Say you want to receive dirty funds worth $3 million. First, you need to get your hands on an NFT. You can buy one on the cheap, or mint your own for $100 or so.

If you want to establish a price history so things don’t appear quite so obvious, you can “wash-trade,” buying and selling the unique token to yourself a few times—under alias accounts, of course—so that the NFT appears to be worth $4 million. Suspicions that wash trading is rife in the NFT space have been growing, and, as Bloomberg points out, wash trading has long been called “crypto’s open secret.”

Now, you can turn around and sell your NFT to your dirty colleague for $3 million in cryptocurrency—a 25 percent loss! You can then cash out on a banked cryptocurrency exchange. If anyone asks where your funds suddenly came from, you simply tell them you sold a precious NFT.

“If you are offering thirty of something, you can establish a fair market value,” Spiro explains. “But if it is a one-of-one, that’s what makes these illicit trades more complicated—and hard to spot, because the price of an NFT is whatever someone is willing to pay for it.”

Logo for Bitcoin Fog, a service whose founder, Roman Sterlingov, was charged on April 28 with money laundering, operating an unlicensed money transmitting business, and money transmission without a license.

Chain Hopping and Tumblers

The fact that NFTs are most often bought with cryptocurrency adds another layer of obfuscation to the mix. Bitcoin is remarkably traceable, as are most other cryptocurrencies. But there are ways of covering up the trail. One method is with “chain hopping.”

“Exchanges don’t publicly record transactions until you withdraw, and it is hard to link deposits and withdrawals,” explains Nicholas Weaver, a researcher at the International Computer Science Institute in Berkeley, who has been studying bitcoin since 2011. “So go to a dodgy exchange, turn your bitcoin into something else, move it onto another dodgy exchange, turn it back into bitcoin, and now the authorities are blinded as to what happened.”

Another way to dust up the trail is with “tumblers,” services that split your payment into small amounts, mix them with other payments, and send them through hundreds of transactions. In April, the operator of Bitcoin Fog, an OG bitcoin mixing service, was charged with operating one of the longest-running bitcoin money laundering services on the darknet, having allegedly moved $335 million worth of illegal proceeds in its 10-year-lifespan.

Cryptocurrency has had a long-standing problem with money laundering. “Some [cryptocurrencies] even include money laundering as first-class features,” said Weaver, referring to so-called “privacy coins” Monero and Zcash, which are designed to keep transactions anonymous.

It would be illogical to assume that combining two fields that are both associated with money laundering—art and cryptocurrency—didn’t lead to more of the same.

A digital artwork featuring the frontman of the band Scooter is offered on OpenSea. (Photo by Jens Kalaene/picture alliance via Getty Images)

The Role of Platforms

A favored approach to deterring money laundering and sanctions evasion is to collect personal information on the people doing the buying and the selling. Art, historically, has had a loose relationship with such so-called know-your-customer (KYC) rules.

In the U.S., unlike in the E.U., art dealers, galleries, and auction houses are not yet subject to the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA)—our country’s main anti-money laundering law—which requires at-risk industries to do things like verify the identity of their customers, record cash transactions, and report suspicious activities.

NFTs have increasingly begun to trade at top auction houses, like Christies and Sotheby’s. According to the 2020 Senate PSI report, the four major auction houses (Phillips and Bonhams are the other two) already have voluntary anti-money laundering (AML) programs in place. They have likely upgraded their programs following the report, which painted a devastating picture of the art industry, to avoid further risk.

“Christie’s has a robust global AML program that requires KYC for all of our offerings, and those standards are no different for our NFT sales,” Christie’s told Artnet News. “Our buyers are never anonymous to us, even if they may be anonymous to the public.”

Sotheby’s, which has also auctioned NFTs, did not respond to a request for comment.

Mainly, however, NFTs trade on specialized online marketplaces. Nifty Gateway, one of the more popular NFT auction houses, is owned by the Gemini exchange.

According to a spokesperson: “Nifty Gateway employs a risk-based approach to KYC and identity verification. For example, before they can remove funds from Nifty Gateway, Nifty Gateway users must have undergone KYC checks on a separate platform. We are continually re-evaluating our approach in light of a rapidly growing and changing industry.”

Nifty Gateway is centralized—meaning all its app software resides in a central location, controlled by the company—and it’s one of the few NFT marketplaces that link directly to your bank account. (It even lets you buy NFTs with cash.) Gemini is registered with the U.S. government’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), a bureau within the U.S. Treasury Department, as a money services business, and it’s widely thought of as one of the more regulated platforms.

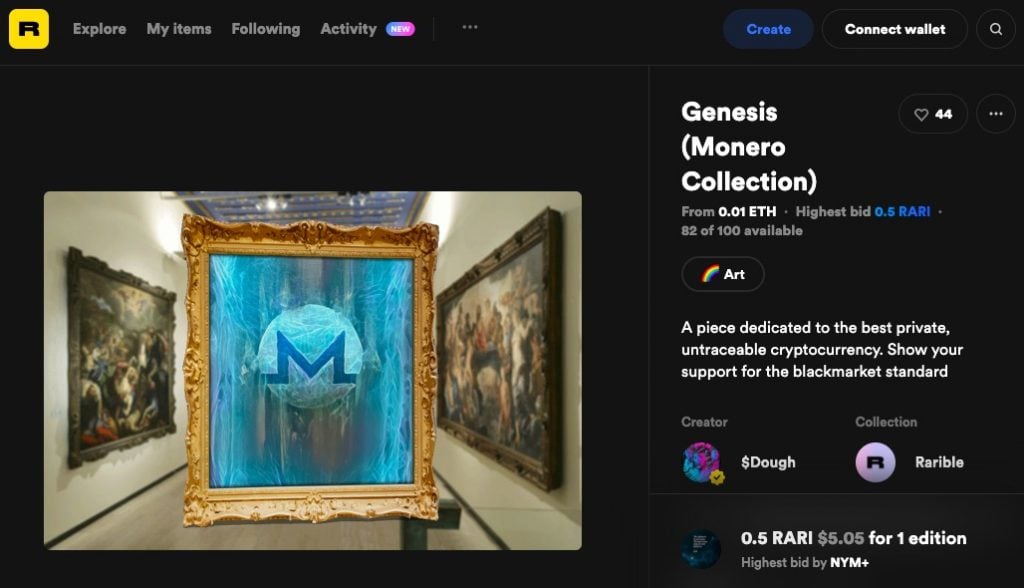

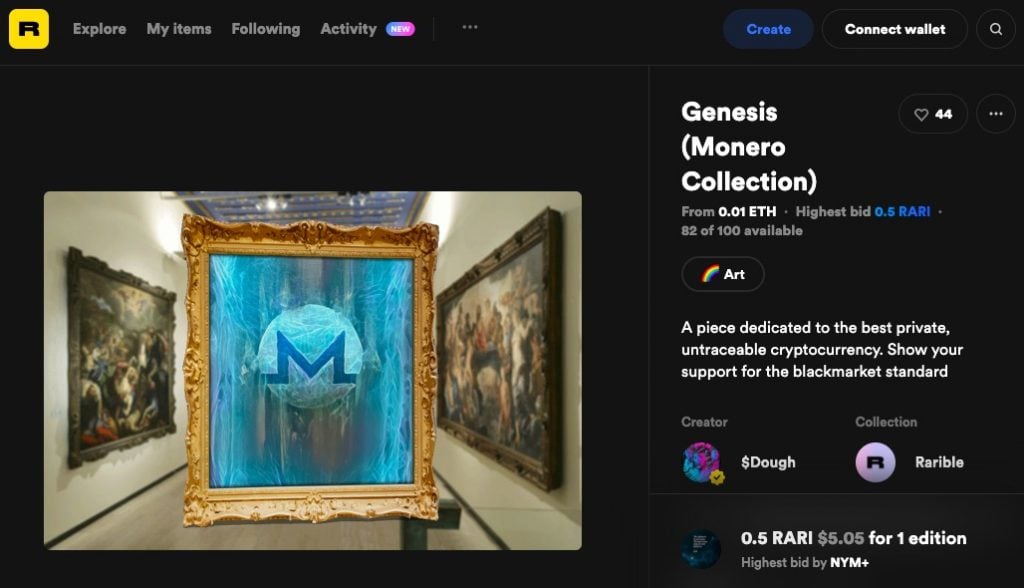

Screenshot of a sale on Rarible for $Dough’s Genesis (Monero Collection), asking buyers to “show your support of the blackmarket standard.”

However, many other NFT marketplaces, such OpenSea, Rarible, and Foundation, have taken a more relaxed approach to KYC rules. These platforms are “decentralized,” meaning that the back-end code runs on the Ethereum blockchain. (Technically, they are what is known as “dapps,” or decentralized applications.)

These marketplaces typically only ask for personal information when you use them to on-ramp from fiat to crypto. Unlike crypto exchanges, such as Coinbase and Gemini, or an NFT marketplace such as Nifty Gateway, they handle virtual assets in a non-custodial way—meaning they never take ownership of tokens. They simply facilitate peer-to-peer trades, matching buyers and sellers.

“KYC is only required when you buy crypto using OpenSea,” Alex Atallah, co-founder of the platform, told Artnet News. (In that case, KYC is handled through Moonpay, a fiat on-ramp that lets you buy cryptocurrency with your credit card.) As he explains it, if you transfer your own crypto onto the platform and buy NFTs with it, OpenSea doesn’t ask who you are. Nor does it ask who you are if you sell your NFT for crypto and move your funds off the platform.

The Capitol building as the Senate resumes debate on the National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) on December 31, 2020 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Joshua Roberts/Getty Images)

Regulators Catch Up

Regulatory changes are coming for the art market—and probably NFTs as well. Since NFTs don’t really qualify as cryptocurrencies (they aren’t “fungible,” meaning you can’t swap out one for another, as you can with bitcoin), some believe they are likely to be swept up into any laws that cover the art trade.

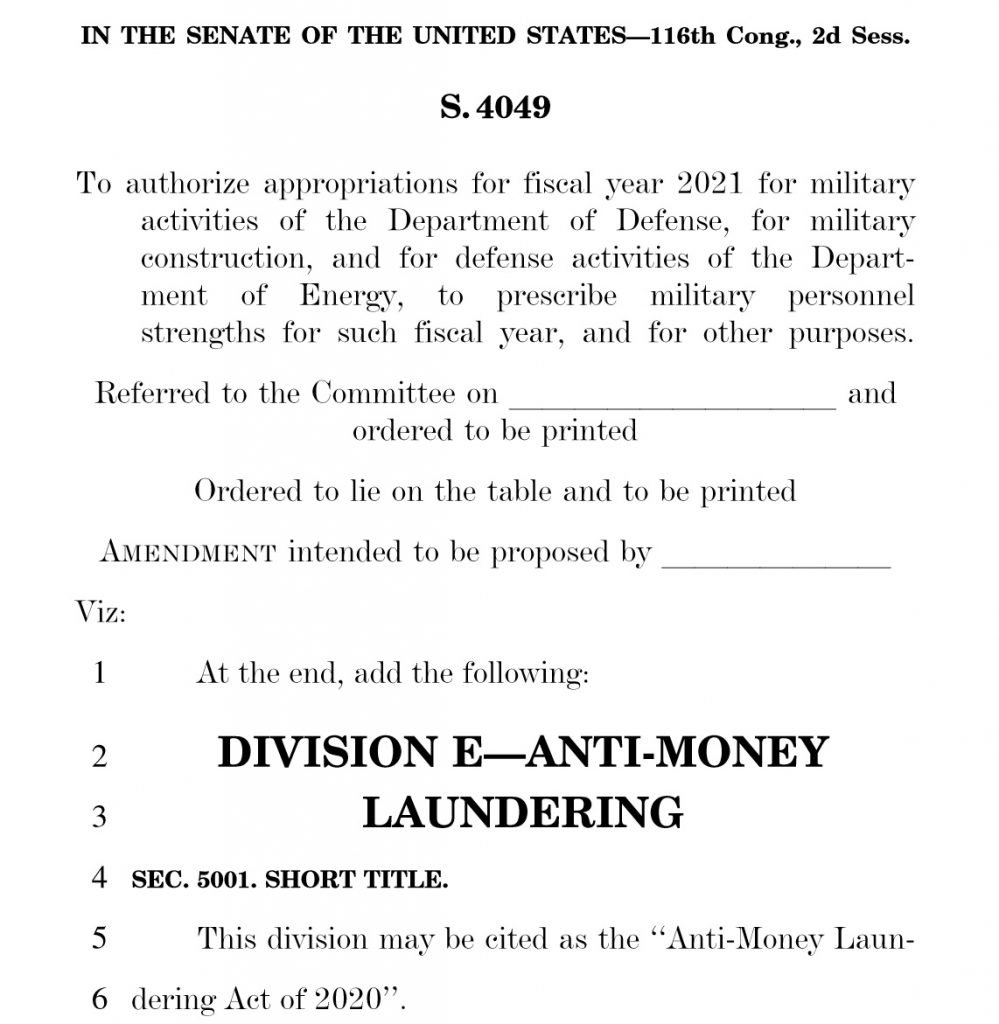

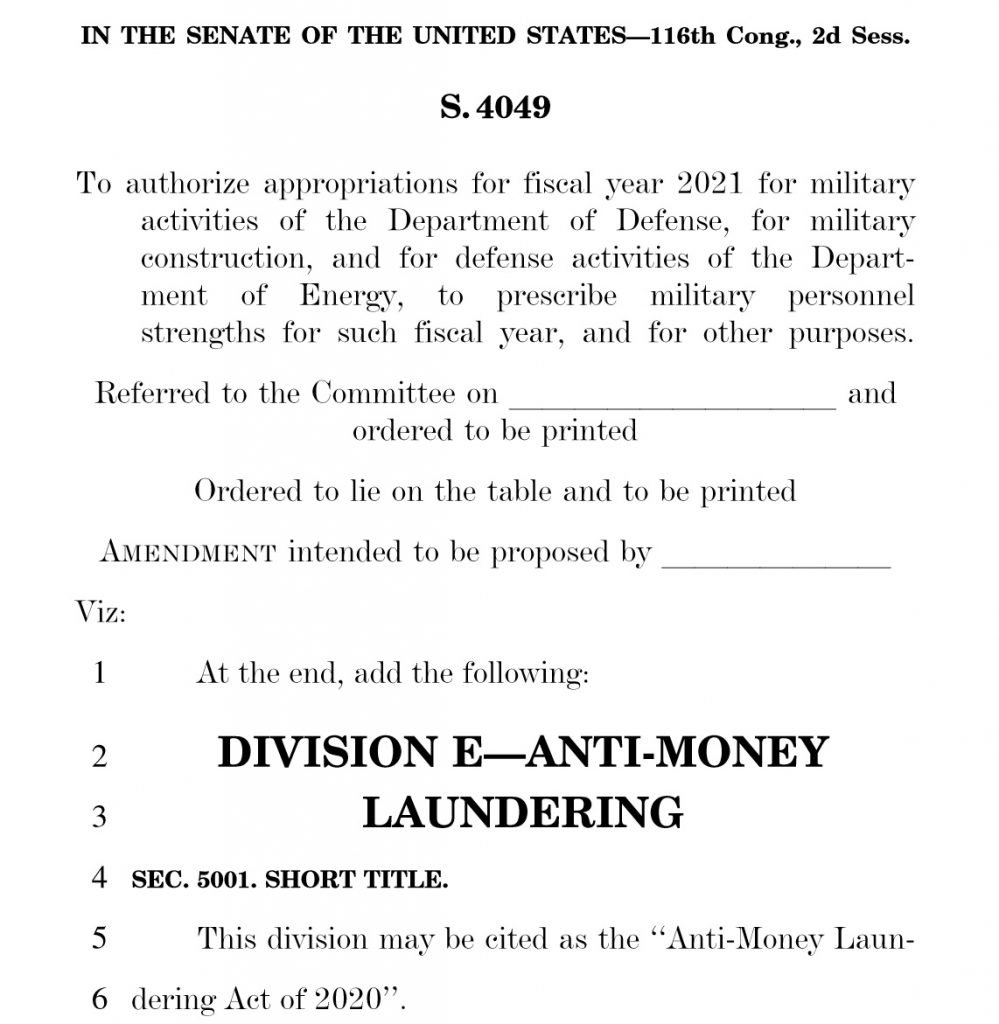

On January 1, Congress passed the Anti-Money Laundering Act of 2020 (AML Act), as part of the National Defense Authorization Act, amounting to the biggest changes to the BSA since the Patriot Act in 2001.

Among the changes, the AML Act extends the BSA to antiquities dealers, making it a lot harder for collectors and investors to conceal their identities. It is up to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network to spell out exactly how this will be implemented. They have until the end of the year to do so.

The AML Act also instructs FinCEN to study the art market. If FinCEN finds significant links between money laundering and high art, it will likely recommend Congress extend the BSA to include the wider art market, too. This has already happened in Europe under the E.U.’s anti-money laundering directives. Experts believe it is very likely to happen in the U.S. as well.

“The art industry narrowly escaped regulation under the BSA this time, very narrowly,” said Katherine Kirkpatrick, a partner at law firm King & Spalding, an expert in anti-money laundering.

Given the likelihood the art trade will be regulated in the future, she believes businesses that sell high-value art—including NFT platforms—should take this opportunity to re-evaluate their AML programs. If they were to inadvertently facilitate money laundering, they could be criminally liable. In addition to legal penalties, their reputations could suffer.

“This is a wake up call for them to say, let’s look at our policies. Do we have a voluntary AML policy? Let’s take a look at that, tailor it to the particular scale and type of risk that we face,” she said.

Screenshot of the AML Act of 2020.

The AML Act also formally extends the scope of the BSA to cryptocurrency exchanges, in keeping with FinCEN’s earlier guidance that virtual currency businesses are money services businesses, and therefore, subject to BSA requirements.

NFTs, on the other hand, aren’t mentioned in the new AML law—not surprising, since NFT mania didn’t explode until the end of 2020. Further Congressional action will be necessary to apply AML regulations to NFTs and the marketplaces they trade on. But they aren’t being overlooked either, and policymakers already have NFTs in their sights.

One bellwether is that in March, the Financial Action Task Force, a Paris-based international watchdog that develops AML standards, issued a draft updated virtual asset guidance which could have implications for NFTs. The FATF isn’t a regulator, but as one of its 37 member jurisdictions, the U.S. contributes to and follows its guidance.

In its draft, the FATF doesn’t specifically name NFTs, but it replaces an earlier phrasing of “assets that are fungible” with “assets that are convertible and interchangeable” in describing the kinds of virtual assets that need regulation. This language change directly targets the trade: NFTs are “convertible” in the sense that when you sell them, you convert them to ether or bitcoin, or in some cases, cash.

If the U.S. adopts the final guidance, those subtle changes in wording give FinCEN the authority to regulate not only existing virtual currencies, but also emerging asset classes such as NFTs.

“What it means is that NFTs are caught,” said Spiro. “There is an inclusion. The FATF are formally acknowledging that there are risks associated with them and there needs to be effective oversight and regulation.”

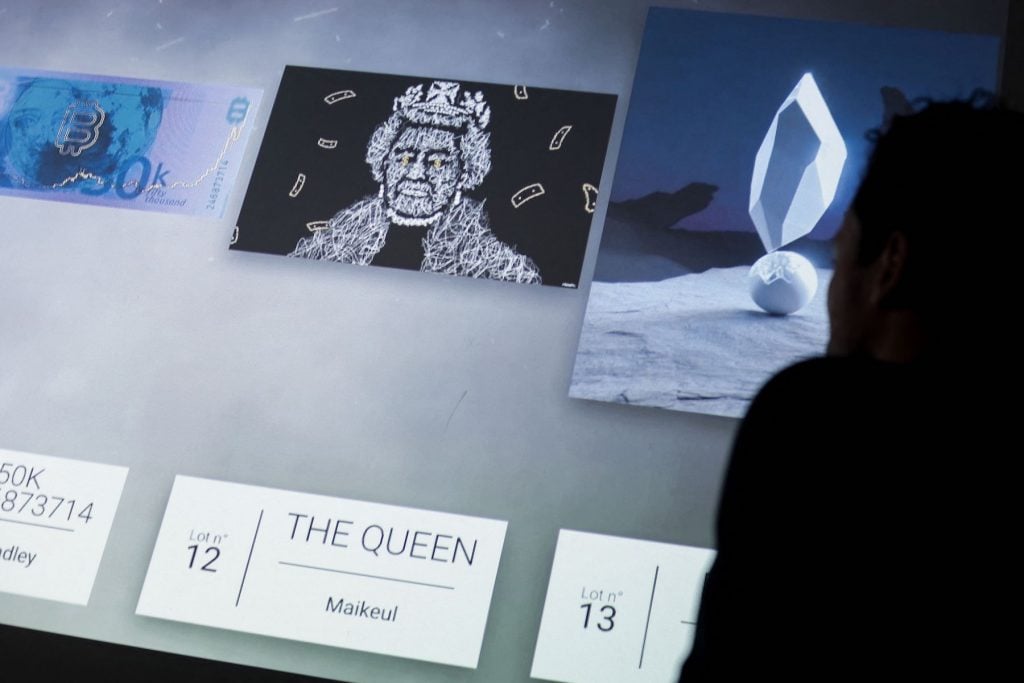

A visitor looks at an NFT which will be auctioned on May 20 at the Millon Belgique auction house in Brussels. (Photo by Kenzo Tribouillard/AFP via Getty Images)

Looking Ahead

At the end of the day, money laundering is about moving money without attribution. Although NFTs have been around for several years, the market only started going crazy in October, and the laws have been slow to catch up. As of now, there is no requirement for NFT marketplaces to implement KYC checks.

“They certainly don’t have to go through what banks do, which is extraordinarily onerous,” said Kirkpatrick. “The real question is should they be doing it? They are fine for now, meaning they are avoiding BSA requirements. But will that change? My best guess is that it will change, because I believe Congress and law enforcement will identify NFTs as a major risk area for the facilitation of crimes, and they will move to fill that gap.”

Until the loophole governing NFTs is officially closed and enforcement steps up, bad actors are likely to take advantage of the NFT market to transfer ill gotten gains, evade sanctions, and fund terrorism—because it offers a path of least resistance.