Artnet News Pro

More Than Meets the Eye: 5 Data-Driven Takeaways From New York’s $1.5 Billion Spring Auctions

Our columnist dove deep on auction metrics to locate the market signals in an unusually noisy season.

Our columnist dove deep on auction metrics to locate the market signals in an unusually noisy season.

Tim Schneider

If you’re still struggling to make sense of this month’s stampede of New York auctions, don’t blame yourself. It would have been a challenge to parse the results even if they arrived in shorter supply. But when you spread the unneven data across yet more mainstay auctions, dedicated single-owner sales, and further-collapsing categories (Did you know Peter Paul Rubens was a modern artist? Or that Etel Adnan, born in 1925, is considered a product of the 21st century?), the struggle starts to feel Olympian—even for people who have been at it for decades.

“I was in the auction business for almost 20 years, and it was very much two days of sales for each collecting category: an evening, and morning and afternoon the following day. Now, it seems to be a week of everything for each auction house,” said Naomi Baigell, managing director of TPC Art Finance.

What’s clear is that the art trade has reached consensus on the grand narrative of spring 2023: It was the season the market finally cooled off. But, based on what I’m hearing, the main topic of conversation has now shifted from “When will the correction set in?” to “Oh my god, how ugly will this downturn get?”

The change in tone is to be expected, given the art world’s tendency to assess things in the most emo terms possible. (It seems like it’s always the best time of our lives or the end of everything, doesn’t it?) Yet a painstaking look at the results from May’s evening sales reveals that the state of play is much more nuanced than the chatter.

In an effort to keep us all from being misled, here are my five takeaways from the maelstrom (with a major assist from our new no-nonsense feature on auction data, By the Numbers).

Craftworkers compare blown-up sections of counterfeit hundred-dollar bills with a sample legitimate bill expanded to 400x actual size. (KAZUHIRO NOGI/AFP via Getty Images)

The Analysis: Is it reductive to judge the performance of any individual sale or seasonal auction cycle with one statistic? Sure. But comparing the hammer total to the total presale estimate (which excludes fees) is still an unusually instructive exercise for anyone who wants an at-a-glance gauge of the market.

By my calculations, the nine art evening sales from Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips generated a hammer total of slightly over $1.23 billion against a total presale estimate of $1.28 billion. To be even more specific, the houses collectively underperformed their low expectations by $48.3 million.

Now, $48.3 million is an awful lot of cash in most contexts. But relative to more than $1.2 billion worth of sales, it’s not that far from a rounding error. That means that the houses collectively performed more or less right up to their low estimates.

So why is the mood in the aftermath of the sales so downbeat? I suspect the sequence of the auctions had a lot to do with it. The hammer total surpassed the presale low estimate in each of the first four evening sales: in order, Christie’s S.I. Newhouse auction (+$8.5 million), Christie’s 20th century auction (+$16.1 million), Christie’s 21st century auction (+$20.1 million), and Sotheby’s Mo Ostin sale (+$1.2 million).

Then, each of the last five evening sales failed to hit that metric, from Sotheby’s modern sale (–$32.5 million) on Tuesday night, to Phillips’s 20th century and contemporary sale (–$2 million) on Wednesday, to Christie’s Gerald Fineberg sale (–$38.3 million) the same night, to Sotheby’s Thursday double-header of “The Now” (–$12.3 million) and the contemporary sale (–$9.1 million).

The Takeaway: This uninterrupted peak-to-valley movement would be one thing if some business-critical news had broken during the intermission separating Sotheby’s Mo Ostin sale from its modern evening sale—say, the collapse of a systemically important financial institution, or confirmation that Congress will fail to raise the debt ceiling.

Nothing of that nature actually happened, though. That makes it a fascinating little experiment in market psychology to consider how differently the past two weeks of evening sales might have been perceived if the four overperforming auctions would have followed the five underperforming ones rather than the inverse.

As it stands, however, I think a lot of art professionals are somewhat underestimating the market’s health because of the quirky, largely random way that the results tailed off from last Tuesday night through last Thursday night. But that doesn’t mean it was all peaches and cream, either, especially since…

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Now’s the Time (1985). Photo courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The Analysis: It’s no exaggeration to say that every auction or auction cycle’s fate primarily depends on the performance of its trophy lots (which we define as works estimated to sell for at least $10 million). This May, bidding for such apex artworks mostly fell on a spectrum between uninspiring and adequate.

The good news is that 30 of the 32 trophy lots at the Big Three houses found buyers. The first exception was Picasso’s Femme assise au chapeau de paille (Marie-Thérèse), which was bought in during Christie’s 20th century evening sale after bidding plateaued at $18.5 million against the $20 million low estimate. The second exception was Yoshitomo Nara’s Haze Days (1998), which Sotheby’s withdrew from The Now evening sale amid doubts that it would meet the reserve price lurking somewhere near its $12 million low estimate.

The less good news is that 17 of the 30 trophy lots that did sell only did so on a final bid beneath their presale low estimate. Nine others hammered within their expected range. Only four sold above their high estimate absent the rocket fuel of the buyer’s premium.

The two top sellers both defied expectations by cracking the $50 million barrier: Basquiat’s El Gran Espectáculo (The Nile) (1983) hammered at $58 million ($67.1 million with fees), well above its estimate in the region of $45 million; and Gustav Klimt’s Insel im Attersee (Island in the Attersee) sold on a $46 million bid ($53.2 million with fees), slightly north of its estimate in the region of $45 million.

The Takeaway: I think a few different things are going on here. First, as much as we (rightfully) talk about how much the art world has benefited from the growth in the number of millionaires and billionaires worldwide over the past several years, that shift has done a lot more to boost the number of buyers willing to pay $500,000 to $1 million for an artwork than the number of buyers willing to pay more than $10 million for an artwork.

Macroeconomic conditions have definitely done damage to the small tranche of potential trophy lot bidders, too; Forbes just reported in April that the 25 wealthiest people lost a combined $200 billion in net worth in 2022. Plus, many, if not most, of the candidates to acquire such big-ticket pieces already own major works by some, if not all, of the artists behind this season’s marquee lots—especially given that we’ve just finished an almost two-year run of storied estates reaching the auction block.

All of this means that buyers were more likely to be choosy this May. Which suggests the identity of the trophy lots mattered even more than usual. If you’re going to spend $30+ million on a Basquiat painting after fees, do you really want Now’s the Time (1983), the rare oval canvas that only reads as a Basquiat if you can recognize the man’s handwriting? Even if you’re prepared to splash out your wealth on a major acquisition, don’t you have to be a very special kind of plutocrat to target the hulking, straight-from-a-nightmare Louise Bourgeois spider?

In short, the pricing data matters, but the art and the investment landscape do, too. The slight misalignment of those three factors this May should have been foreseeable and looks blatantly obvious in retrospect.

Pablo Picasso, Nature morte à la fenêtre (1932). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The Analysis: Across all nine art evening sales at Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips, the houses made direct financial guarantees for 87 lots with an aggregate low estimate of $730.9 million. That amount equates to 57.1 percent of the total presale low estimate of $1.28 billion.

Yet the Big Three farmed out the overwhelming majority of the risk to third-party financiers before showtime. In all, 85 lots carried irrevocable bids adding up to $663.5 million—just shy of 52 percent of the total presale low estimate.

In other words, of the $730.9 million worth of guarantees made by Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips, the houses thought it wise to reduce their direct exposure to a measly $67.4 million via irrevocable bidders.

The Takeaway: The volume of guarantees and third-party risk sharing was simultaneously notable and business as usual for all three houses by this point in the 21st century. A house can only sell what it can manage to consign, and offering financial guarantees is simply part and parcel to making the most compelling pitch to the owners of valuable artwork, all of whom are probably being pitched by multiple houses.

“I have to take into account the psychology of getting the consignment. I can’t blame a sale for not doing well because of what happened competitively between the houses when they were putting the sale together, or what’s happening in the global picture in terms of economics,” said Baigell of TPC Art Finance.

In this sense, the real signal of performance anxiety this spring was Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips’s decision to share so much of their risk with third parties. Shelling out house guarantees was, in most cases, probably a necessity; bringing in irrevocable bidders was not. That the Big Three did the latter at such grand scale suggests to me that they were pretty nervous about the response from the bidding pool.

For indelible proof that the nerves were justified, look no further than Christie’s Fineberg sale last Wednesday night. The 65 lots on offer carried exactly zero point zero dollars’ worth of house guarantees and irrevocable bids, a highly unusual arrangement for a high-value estate being auctioned in the 21st century. Fineberg’s executors were not exactly rewarded for their courage, either, as the hammer total ($124.7 million) landed almost 25 percent beneath the presale low estimate of $163 million.

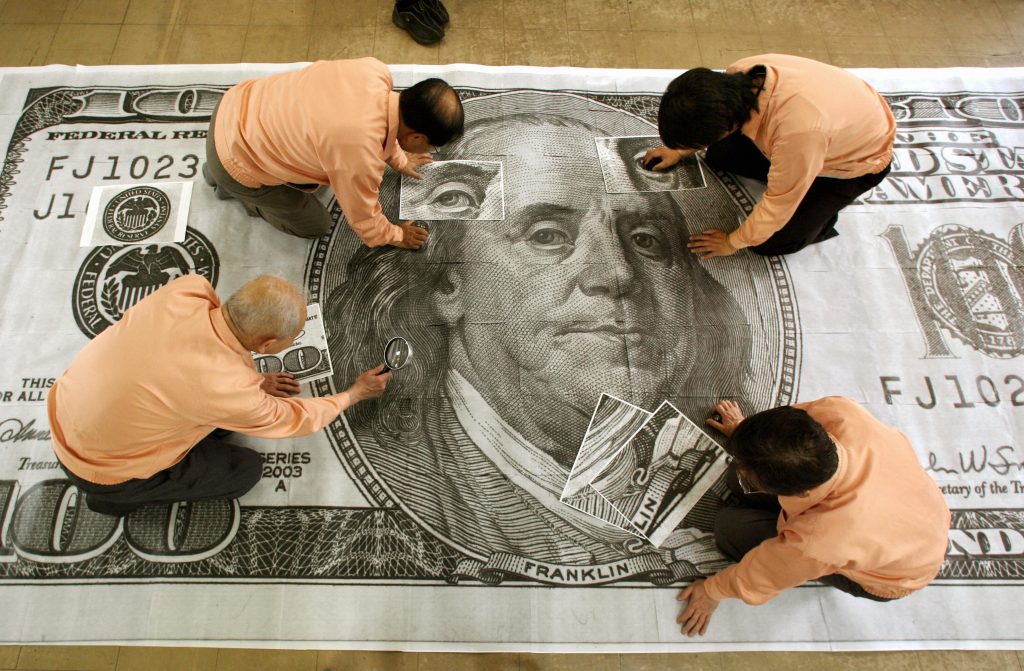

Gerhard Richter, Badende (1967). Courtesy of Christie’s.

The Analysis: Even counting withdrawals, the overall sell-through rate for the nine evening auctions was 83.4 percent. (It rises to just over 89 percent if you omit the 21 withdrawn lots from the calculus.) That’s a very good hit rate for any season, let alone one that’s supposed to affirm a long-awaited market downturn.

So, what gives? It takes months to assemble an entire sale, meaning that the market conditions in which specialists assign estimates (and guarantees) to win consignments may not match the market conditions in which the works actually cross the auction block. No matter how of-the-moment the lots on offer might be, then, every auction has one foot stuck in the past, to some extent.

But while published estimates rarely change ahead of an evening sale, reserve prices can be as mobile as the house and the consignor want them to be. And this May, they moved further and faster than they had in a long time to try to offset the steep rise in interest rates and other intensifying macroeconomic headwinds in the intervening period.

Christie’s CEO Guillaume Cerutti confirmed the house had “adjusted the reserves to make it work” in the Fineberg sale. The tweaks were most obvious at the top level, as both of the auction’s trophy lots (Gerhard Richter’s 1967 Badende and an untitled Christopher Wool canvas from 1993) hammered for barely more than half of their $15 million low estimates.

It’s unlikely that Christie’s was alone in reducing reserve prices for select nonguaranteed lots. The same evening as the Fineberg sale, for example, a 1937 Joan Miró drawing at Phillips hammered 50 percent below its $600,000 low estimate. At Sotheby’s one night earlier, an untitled Cy Twombly canvas from the Mo Ostin collection sold on a $10 million bid despite its $14 million low estimate.

Whether or not the Twombly transaction was enabled by a late-breaking lowering of the reserve, Sotheby’s and its consignors arguably should have been more flexible more often; factoring in withdrawals, the two worst sell-through rates of the spring evening sales came in the house’s modern (74.1 percent) and The Now (76.0 percent) auctions.

The Takeaway: Art advisor Benjamin Godsill put it to me this way after the final evening auction: “Now that we have exited the era of free money, I think more conservative estimates should (and will) be the order of the day going forward.”

Had that happened sooner, the spreads between hammer totals and presale low estimates this May would have been narrower. But since the latter were often relics time-traveling forward from a headier if quite recent epoch in the market, the numbers alone distort buyers’ actual level of hesitance.

As David Galperin, Sotheby’s senior vice president and head of contemporary art, said after last Thursday’s The Now and contemporary auctions, “Where there were great works at the right price, there was incredible depth [of bidding].”

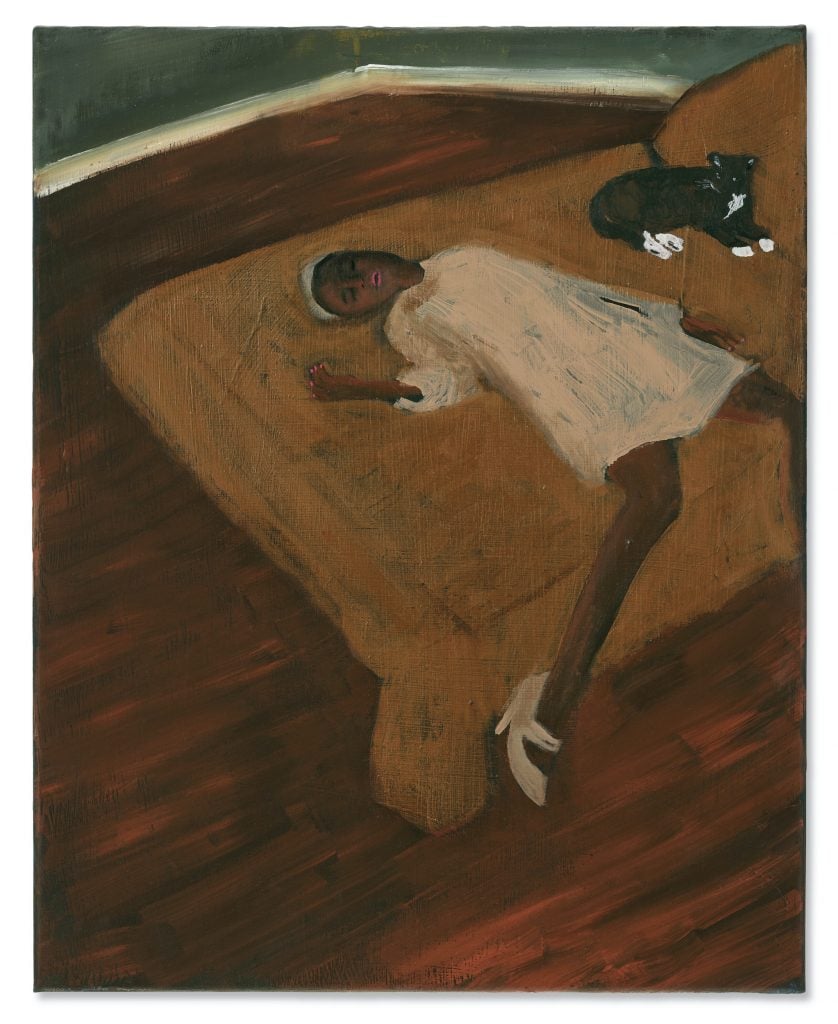

Danielle Mckinney, We Need to Talk (2020). © Christie’s Images Limited 2023. Courtesy of Christie’s.

The Analysis: One of the oldest mantras in the art market is that most collectors tend to respond to instability by redirecting their money from works by less proven artists to works by established greats who can be trusted as stores of long-term value.

This “flight-to-quality” concept, borrowed from finance, makes a lot of sense in theory. I’m already seeing some people dust it off to explain the less-than-satisfying macro results this month. My quibble? There seems to be almost no evidence whatsoever that it actually happened during the past two weeks’ evening sales.

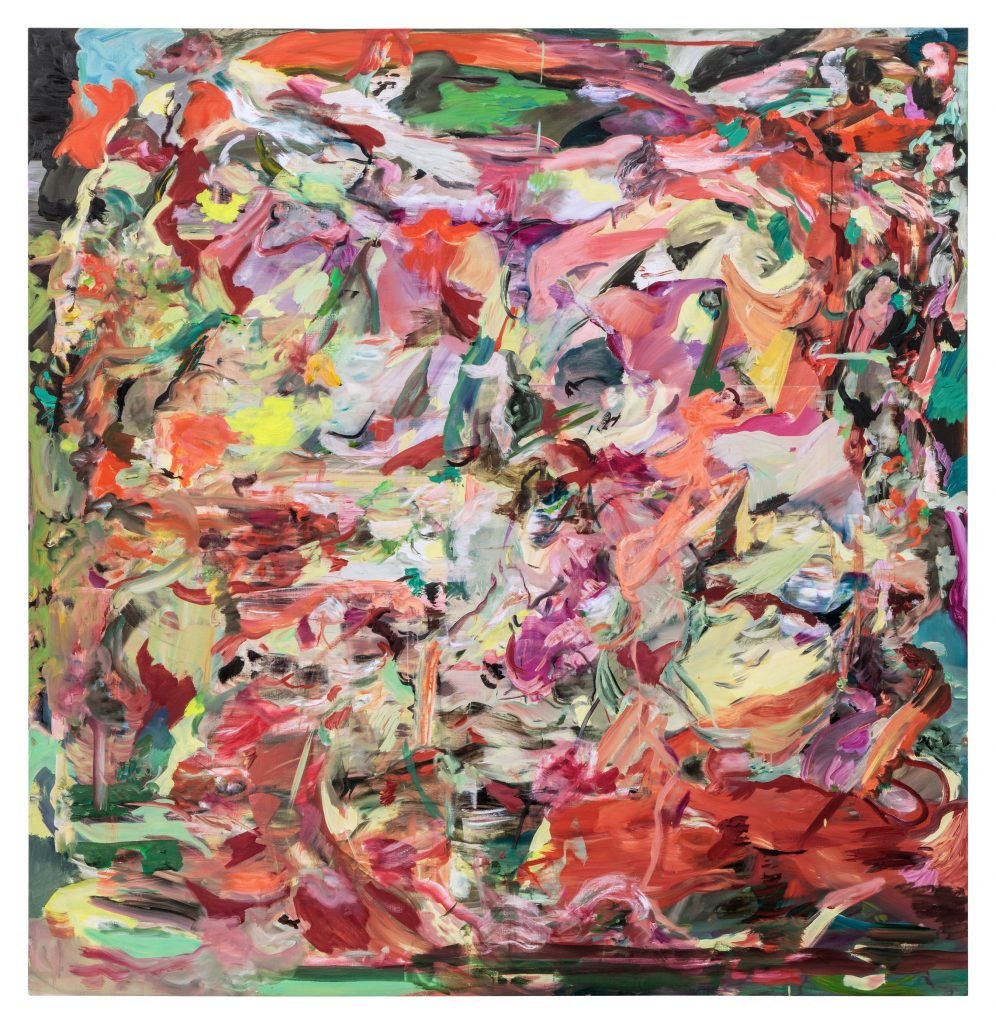

Look at the auctions dedicated to young artists. Christie’s 21st century evening sale boasted a hammer total 31.6 percent higher by value than its presale low estimate, partly thanks to works by ultra-contemporary artists Louis Fratino, Vojtěch Kovařík (in his first evening sale), Danielle Mckinney (ditto), Emma Webster, and Robin F. Williams all selling on bids surpassing their high estimates. (“Ultra-contemporary” is Artnet’s in-house designation for artists born in 1975 or later.)

Sotheby’s The Now auction fared considerably worse by the numbers alone, but the main weakness was the withdrawal of Yoshitomo Nara’s aforementioned Haze Days, a 25-year-old painting by a 63-year-old artist. Set that aside, and the youngest artist to have their work bought in or withdrawn from the auction was Wade Guyton, who turns 51 this year. (The only other two candidates were Louise Bonnet and Laura Owens, both born in 1970.)

Meanwhile, of the 19 The Now lots to sell, six by ultra-contemporary artists were bid up beyond their high presale expectations. The artists in question were Justin Caguiat, Njideka Akunyili-Crosby, Jadé Fadojutimi, Julien Nguyen, Angel Otero, and Portia Zvavahera.

This same counterintuitive divide was even starker at Phillips’s 20th century and contemporary evening sale. Some of the auction’s strongest performers relative to presale estimates included Noah Davis (who would have turned 40 this year) and ultra-contemporary talents Ewa Juszkiewicz, Sanya Kantarovsky, and Caroline Walker. The biggest disappointments were withdrawn works by Ed Ruscha (estimated to sell for at least $2.5 million) and Robert Motherwell (estimated to sell for at least $1.2 million), followed by passed lots from sexagenarian Lisa Yuskavage (low estimate: $700,000) and Joan Miró (low estimate: $500,000), who was born 130 years ago.

And at the risk of pummelling a dead horse, the Fineberg auction was chock full of postwar and contemporary greats whose legacies are already secure. The response from bidders, according to my colleague Katya Kazakina, was that “at times, the packed Rockefeller Center salesroom felt like a fire sale.”

The Takeaway: It’s true that plenty of canonical artists performed well in this auction cycle, and that ultra-contemporary talent wasn’t bulletproof as a category. Just don’t let anyone convince you that demand for fresh-faced artists is about to vanish like a mirage in the desert. The contours of the market at large are most definitely shifting, but we’ll all need more than generalities about birthdates and institutional track records to guide us through what comes next. Godspeed.