Market

It’s a Weird Time for Photography. What Does That Mean for the Photo Market?

Though photography sales have contracted over the last two years, institutional interest is up.

Though photography sales have contracted over the last two years, institutional interest is up.

Margaret Carrigan

A version of this article originally appeared in The Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know art industry intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy. Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access—subscribe now to receive the newsletter in your inbox every Friday.

It’s a weird time for photography. Thanks to the advent of camera phones, humans now produce millions of photos per second—trillions per year. And thanks to the rise of generative A.I., photorealistic images are flooding into our already photo-saturated existence. They have also won prestigious photography awards.

Where does this leave the photography market? This week, I went to the 27th edition of Paris Photo, considered the world’s leading photography fair, to find out. Here’s a quick snapshot of the past, present, and future of the field.

Paris Photo 2024 at the Grand Palais in Paris. Photo: Florent Drillon. Courtesy of Paris Photo

Past

Price points for photographic works have historically been lower than other fine-art categories. There are two main reasons for that. One is that most photos are editioned rather than unique. The other is that photography has not always been seen as fine art and sometimes still exists in a liminal space between art and broader visual culture. The increased accessibility of digital images and image-making tools over the last decade has led to fears of a further decrease in prices, which can be seen at the very top end of the market.

Take for instance, Hiroshi Sugimoto, one of the best-known contemporary photographers. According to the Artnet Price Database, four of his works have sold at auction for more than $1 million—but all between 2007 and 2008. It’s a similar story for Cindy Sherman, who has had 21 photographic works sell over the million-dollar mark; of these, all but three sold more than a decade ago. Andreas Gursky, a market all-star in this category, had 32 works sell for over a million (sometimes many millions) between seven and 17 years ago. At Paris Photo, his Prada III (1998) was being sold for around $500,000 at Zander Galerie.

An installation shot of Zander’s booth at Paris Photo, with Andreas Gursky’s Prada III seen on the left. Courtesy of Zander Galerie.

There were million-dollar pieces at this year’s fair, though. The most expensive was a collaged gelatin silver print from Gordon Matta-Clark’s “Splitting” series, priced at $2.7 million at Patinoire Royale’s booth. (The gallery currently has a show dedicated to the artist at its Brussels outpost up through December.) Against the backdrop of general market contraction over the last year and geopolitical unrest—the fair opened to VIPs just after Donald Trump declared victory in the U.S. presidential election on Wednesday morning—big sales weren’t guaranteed. “Decisions may take a little longer to be made,” the fair’s director Florence Bourgeois said ahead of the opening. Nevertheless, she noted that there was a “strong international presence” at the fair, particularly from American institutions such as MoMA, which “underscores the growing prominence of the event.”

Present

In the lower- and mid-market range, prices have remained fairly stable. That doesn’t mean the photo sector has been immune from the recent downturn, but it has suffered less. Artnet’s data shows that photography sales at auction are down just over 10 percent so far this year compared to last year. In contrast, there was a nearly 30 percent drop in art sales at auction in the first half of 2024 versus the same period in 2023.

What has grown, according to Bourgeois as well as many dealers, is institutional interest in photography, especially for lesser known or historically marginalized artists, mirroring a larger trend within the art market. To that end, Paris Photo introduced a new curated “Voices” sector this year to spotlight overlooked practices. (Its introduction was aided by the fact the event had more floor space to work with as it returned to the Grand Palais this year, which had been closed for refurbishment since 2021.) Early sales from the sector included six works by Brazilian photographer and activist Claudia Andujar, priced at $12,000 each, brought by Vermelho gallery, and a piece by Chinese artist Cai Dong Dong, known for blending photos and readymades. Brought by Shanghai’s M97 Gallery, it sold for $15,000.

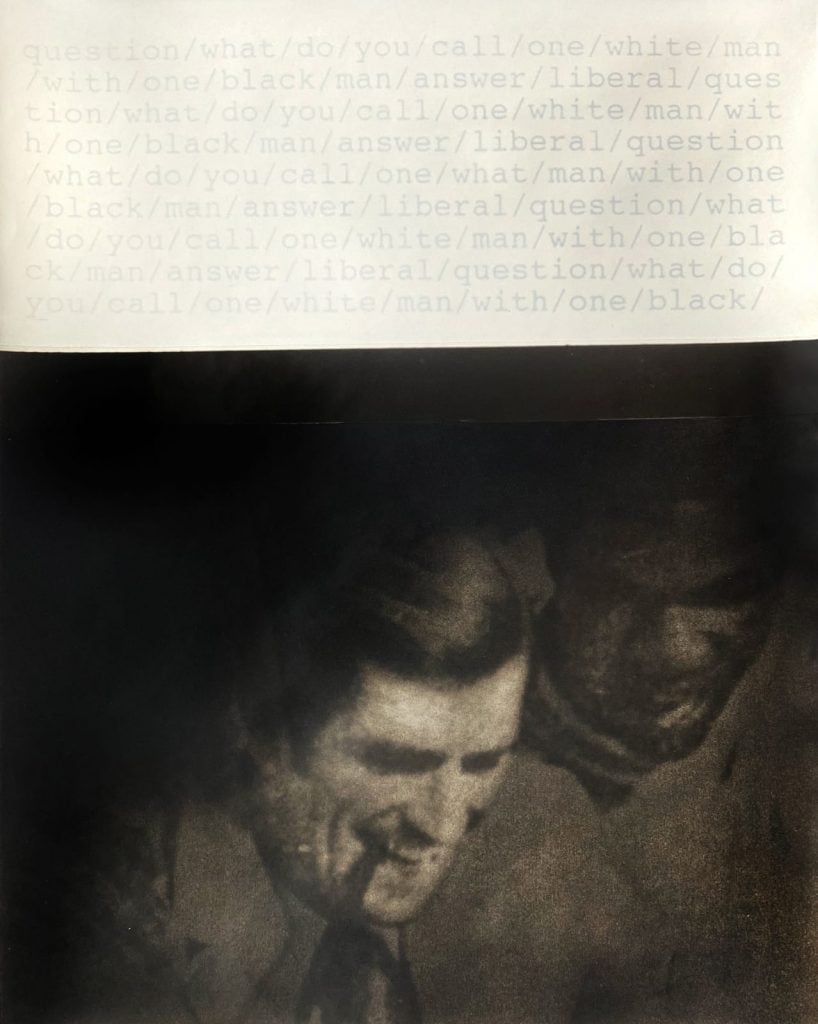

Christian Walker, Mule Tales (1990–95). Courtesy of Jackson Fine Art.

With the hope of capturing more institutional attention, Malia Schramm, the director of Atlanta’s Jackson Fine Art, dedicated her booth in the main section of the fair to the work of Christian Walker, an experimental photographer active in Boston and Atlanta who captured queer and Black life from the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. Though Walker showed frequently while he was alive—most notably in a 1994 Whitney show on representations of Black masculinity, curated by Thelma Golden—much of Walker’s archive was lost after his death in 2003. “He sort of fell off the map,” Schramm said. That changed last year, when New York’s Leslie-Lohman Museum mounted a retrospective of his work. At the stand, works were priced between $7,375 and $9,800, and institutions such as the Dallas Museum of Art had already expressed interest in the first few hours of opening day.

Similarly, Mariane Ibrahim, who has gallery spaces in Paris, Chicago, and Mexico City, focused her booth on two bodies of work by conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady (priced from $45,000 to $60,000) with the intention of growing the artist’s European museum presence. Included were photo diptychs from the 1990s series “Miscegenated Family Album,” editions of which are already housed in major U.S. collections such as the Brooklyn Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, as well as prints from an ongoing series featuring a medieval knight figure known as Lancela Palm-and-Steel, the artist’s most recent performance persona.

An installation view of Lorraine O’Grady’s works at Mariane Ibrahim’s Paris Photo booth. Courtesy of Mariane Ibrahim.

O’Grady’s “work is very rooted in European history and should be more visible here,” Ibrahim said.

Future

Advancements in camera technology have ignited debates over what constitutes a photo for pretty much as long as photography has existed. While the market remains dominated by “traditional” photographic prints, there is an increased presence of digital art at Paris Photo, although it is largely limited to the “Digital” sector, which was introduced in 2023. Still, it’s a sure indicator of the growing acceptance of digitally created and A.I.-generated work within the field.

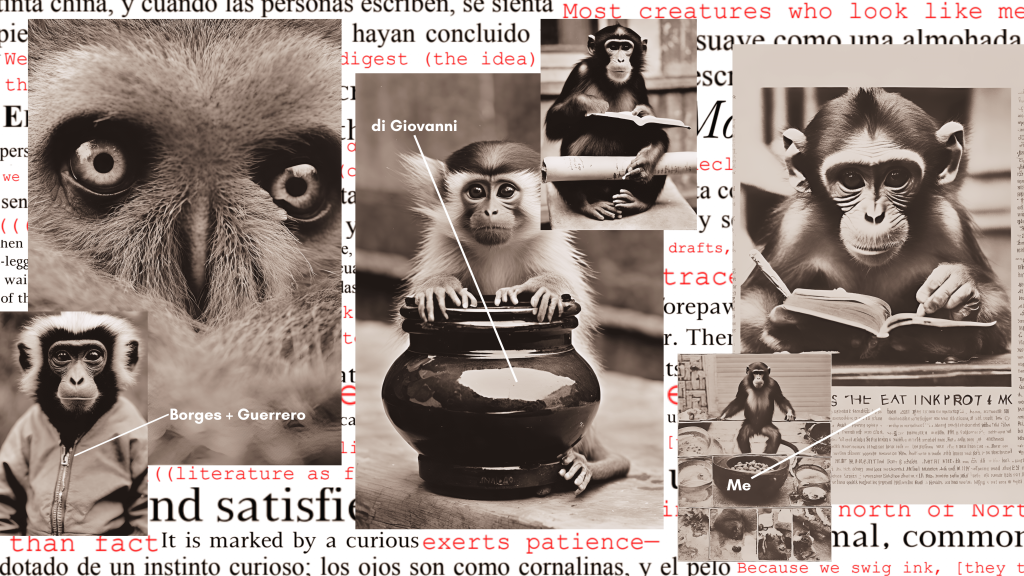

Office Impart brought works by two artists who are working with A.I.: Ana Maria Caballero and Jonas Lund. When asked how much of a market there was for A.I. works, Johanna Neuschäffer, who co-founded the Berlin gallery, said “it depends on what you’re selling.” Two of the three Caballero works, priced at roughly $10,000 each, had already found buyers within the opening hour of the fair. The Colombian-born artist feeds her poems about collectively imagined creatures—cryptids and mythical figures like the Loch Ness Monster—into open source A.I. models to create “collectively imagined images.” Buyers receive a five-piece digital set consisting of the original poem, the collage, and three A.I.-generated image files.

Ana Maria Caballero, The Monkey of the Inkpot (2024), from the “Being Borges” series. Courtesy of the artist and Office Impart.

By the end of the second day of the fair, 10 of the 15 galleries included in the Digital section had reported sales. At Louise Alexander/Fellowship, 11 animation works from Trevor Paglen’s “Evolved Hallucinations” series sold for $3,000 each. Nearby, LaCollection sold out Jack Butcher’s “Latent” series—a collection of 80 unique works, including both physical prints and NFTs—for a total of around €300,000 (about $327,000).

Neuschäffer said that there is still a lot of collector education to be done before digitally rendered and A.I. works are fully embedded in the market, “but people are interested.”

There are very real concerns about how A.I. might alter the trajectory of photography, its effects on the livelihoods of professional photographers and the spread of misinformation chief among them. Yet a curated selection of Surrealist and Surrealism-inspired photos on display throughout Paris Photo, picked by film director Jim Jarmusch, offers a good reminder that photography in every era has always been a little bit weird—and that’s a good thing for artists.