Market

Art Dealers Are Notorious for Obscuring Prices. But as the Market Shifts Online, Many Are Finally Embracing Price Transparency

The surge in online viewing rooms is poised to change the art industry's uneasy relationship to price transparency.

The surge in online viewing rooms is poised to change the art industry's uneasy relationship to price transparency.

Darla Migan

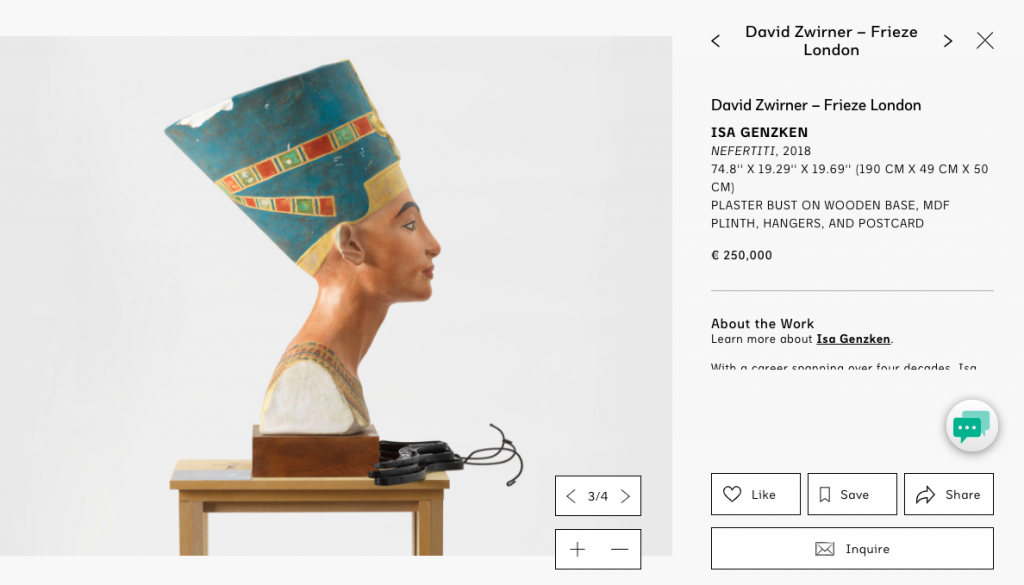

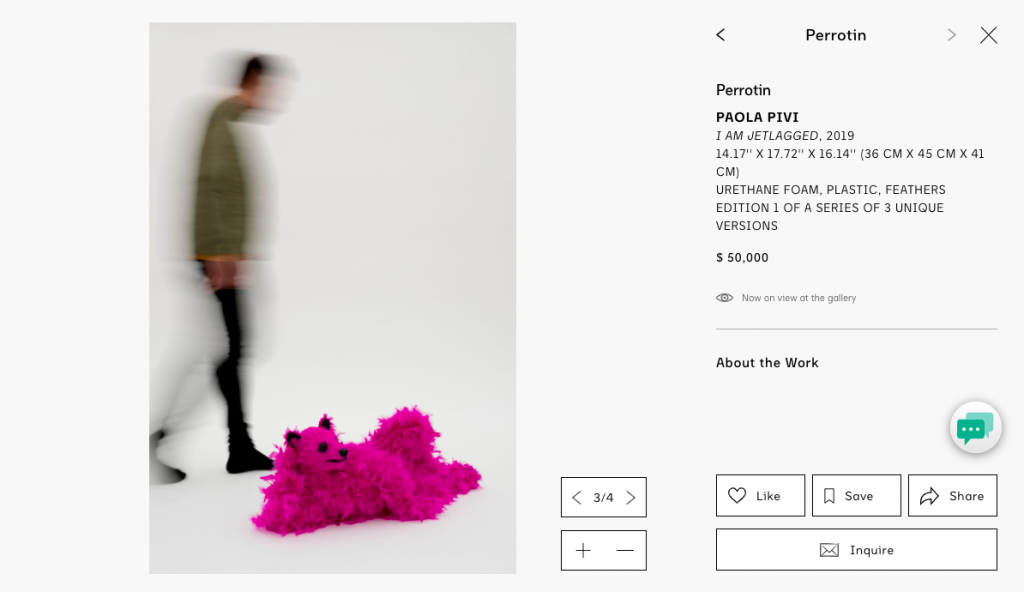

As collectors clicked through Frieze London’s first online-only fair last week, they found plenty of similarities to fairs of years past. David Zwirner was there with photographs by Wolfgang Tillmans and William Eggleston; Pace offered sculptures by Lynda Benglis; Perrotin had works by JR and Daniel Arsham.

But there was one key difference: Almost across the board, prices were clearly listed.

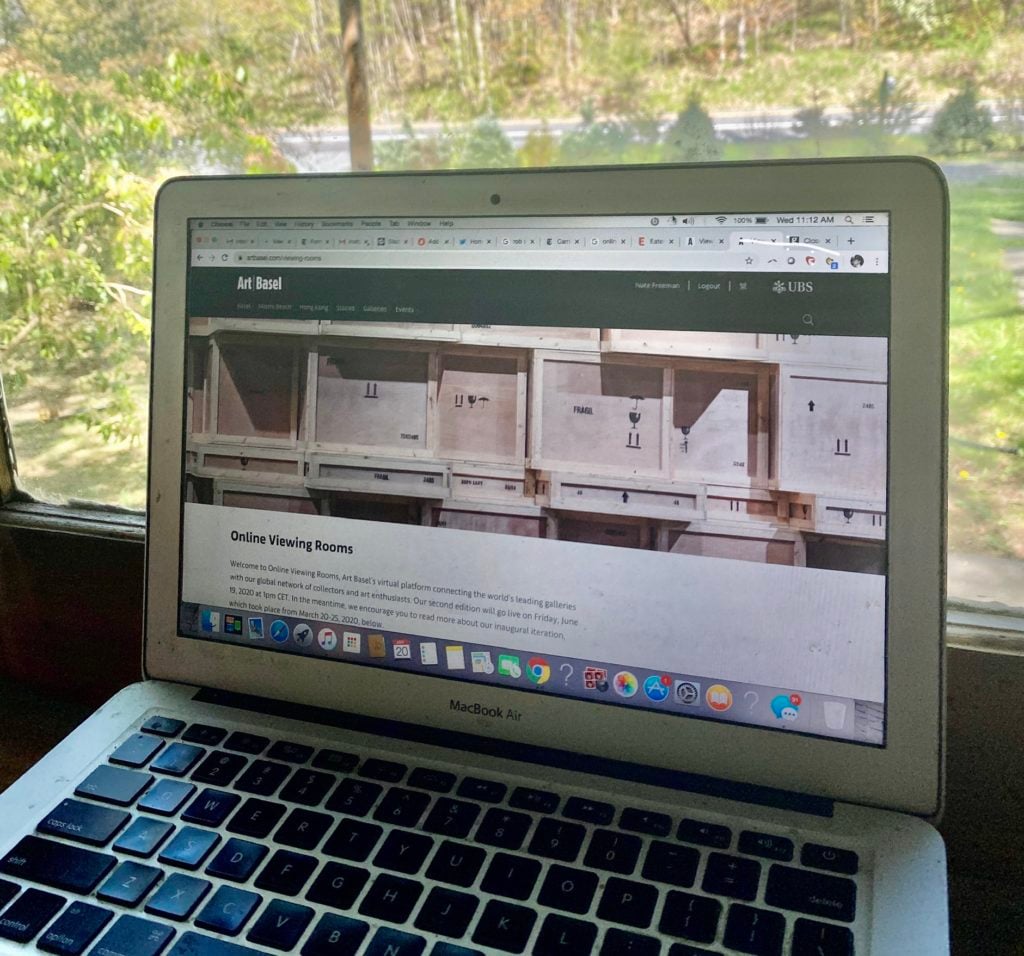

The shutdown that rippled across the globe in the first half of 2020 accelerated the development of online viewing rooms and, with them, pricing in the notoriously opaque art market has grown markedly more transparent. Galleries at Art Basel that never would have posted prices on their booth walls suddenly opted to include them in their online “rooms” at the digital edition of the Hong Kong fair in March—the kind of one-glance transparency that buyers today expect when shopping online.

David Zwirner’s viewing room as part of Frieze London 2020. Courtesy Frieze.

Around the same time, David Zwirner launched an online sales platform to sell works by smaller New York galleries that were struggling to stay afloat amid the lockdown. They too tended to list prices.

“Having a price visible to all audiences, not just VIP collectors, who were the only ones privy to that information in the past, moves the art world into a positive and more open direction,” Elena Soboleva, director of online sales at Zwirner, tells Artnet News.

Thaddaeus Ropac, who runs galleries in Paris, Salzburg, and London, is the rare dealer who has long displayed an openness toward disclosing prices. “At the fairs, we are happy to tell anyone interested and this conversational aspect is part of what makes the experience so personal and social,” he says. But the shift online has pushed him even further toward transparency. “With prices visible on our online viewing room we found that incoming inquiries tended to be serious clients with a definite interest in the works available and that new collectors or those unfamiliar with an artist were able to inquire with confidence.”

Technically, galleries—at least in the art market capital of New York—are supposed to post prices just like any other retail store. Since the mid-1960s, New York City’s consumer protection and regulatory agencies have legally required galleries to conspicuously post prices on their exhibition floors. But art dealers ignored the law and, in 1988, the agencies vowed once again to enforce it in order to combat the “price manipulations” that the city’s department of consumer affairs said were “endemic” to the art market.

Perrotin’s viewing room at Frieze London 2020. Courtesy of Frieze.

For the next three decades, however, galleries carried on flouting the rules—because they had significant business incentives to do so. For one thing, a gallerist may not want to do further harm to an artist whose prices are flagging by displaying the markdowns. They may also not want to disclose prices to competitors, or reveal the preferential prices they give to certain loyal or VIP collectors.

“Not displaying prices can create room to maneuver when a client walks into the gallery,” says Olav Velthuis, a sociologist of the arts at the University of Amsterdam. “Depending on the dealer’s assessment of his willingness to pay, the price can be adjusted upward or downward.”

Bucking convention might also delegitimize a gallery in the eyes of collectors who take a traditionalist not-how-things-are-done-here view of prices in the art market. “It is considered not ‘chic’ and is part of a wider ethos within the art market that monetary concerns are vulgar or impure and should not contaminate ‘pure’ artistic or aesthetic concerns,” Velthuis says.

The Art Basel viewing room as seen on a laptop. Photo courtesy Nate Freeman.

For the earliest patrons of the arts, price was no object. You could either afford to participate or you couldn’t, and the marketplace largely retains this Renaissance-era convention. But with the rise of the salon in the late 18th century, patrons began to disguise the financial aspects of the exchange. They saw themselves not merely as shoppers but instead “understood themselves to be joining a conversation,” says Nathan Clements-Gillespie, artistic director of Frieze Masters.

Dealers and collector-patrons colluded to claim that both sides were motivated purely by the priceless attributes of art, and not its role as a status marker, a symbol of wealth, an asset, and a form of capital.

“Historically, the art market has lacked transparency because the symbolic value of an artwork had to be highlighted as opposed to its existence as a commodity comparable to other non-symbolic goods,” says the art advisor Marta Gnyp. “And yet, despite the supposedly priceless quality of art, art functions not only as a socio-cultural market but also as a carrier of economic capital.”

The complex set of less-than-transparent mechanisms that determine art’s value also makes it easier to obscure its role as a commodity. For one thing, art isn’t produced on the scale of a global retailer with a uniform price structure. Another reason for the industry’s lack of price clarity is that it functions more like the stock market, says Hong Gyu Shin, who runs New York’s Shin Gallery.

“The lack of price availability of artworks is related to the various ways the value of art changes, which, like a stock, is reflected by the activities of various actors,” he says, and “the potential for art to either increase or decrease in value.”

But even still, the financial value of art is not only dependent on the price willing sellers and buyers agree upon, but also on art-historical references, provenance, and other areas of knowledge that are by nature not public. Instead, this insider knowledge is often exclusive to deep networks of families, business associates, and institutions.

Amani Lewis, Negroes in the Trees #3 (2019), which appeared in Christie’s “Say It Loud” sale. Image courtesy the artist and Destinee Ross-Sutton 2020.

When we claim that the art market lacks transparency, it would be more accurate to say that it lacks transparency for some people. “Value in the art market—as in most markets—is more transparent than it might first seem,” says Frieze’s Nathan Clements-Gillespie. “Value is clear to those who have done their homework and have researched the prices achieved in recent transactions, before committing to one themselves.”

While prices have not always been readily available, established collectors who understand how provenances work, know the patterns of pricing for a particular medium, or have relationships with galleries or advisors will have a better sense of what a work of art costs than a novice collector. Price availability, on the other hand, may be only helpful to a buyer without the knowledge and networks of a more experienced patron.

“For new collectors, visible pricing is a key educational facet of learning what is within their budget and builds confidence in their choices,” Soboleva says. “Collectors are excited when they discover David Zwirner has many works under $10,000, and that is wonderful to see.”

These new non-connoisseurs may include speculators who buy art purely as a financial asset, but also more welcome categories of collectors who had previously been shut out from the market simply due to their race or class.

Eniwaye, The Breakfast (2020). Image, courtesy the artist and Destinee Ross-Sutton 2020

The contract arranged by curator and art advisor Destinee Ross Sutton for the Christie’s selling exhibition “Say It Loud (I’m Black and I’m Proud)” in August 2020 functions as a potential model for how to balance the upside of price transparency—to entice new collectors—while also guarding against speculation. The terms were that 100 percent of the sales would go to the artist, with a five-year hold on resale, at which point buyers who do choose to resell must give 15 percent of the profit back to the artist.

“I don’t want this to be a ‘thank you, come again’ situation—I want it to go beyond that,” Ross Sutton says. “There is a value in being a true steward of the work and potential patron of the artist and the arts, as someone who is trying to help move the culture forward in any way, as opposed to just buying and profiting from it.”

The worry among some that price transparency is eroding connoisseurship is not likely to go away anytime soon. And it remains to be seen whether new collectors and, in turn, the artists they support, really do benefit from greater price availability in the long term. Prices alone do not offer enough information to determine a good value when it comes to art. But since the online art marketplace appears here to stay, those once elusive price tags may be, too.