For the past five years, Emmanuel Di Donna has staged meticulously installed shows every six months at his eponymous jewel box of a gallery on Madison Avenue. Last month, he was carefully building out a show of work by Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, a key figure in postwar European abstraction who is widely considered to be Portugal’s most important contemporary artist. It was set to be the most important survey of the her work in the States in decades.

Instead, it never opened. In early March, New York’s inessential businesses—including galleries—were shut down for the foreseeable future. So instead, Di Donna worked around the clock to build out in a matter of days something that for years he did not think he needed: an online viewing room.

“Nothing compares with being confronted by the work, but this is as close as it gets with the technology as it exists,” Di Donna told Artnet News. “It has all the little things that make our shows what they are—the coloring, the certain sobriety. I think this viewing room is a very good reflection of how we do shows.”

A screengrab of Di Donna’s online viewing room. Photo courtesy Di Donna.

Such is the situation of art dealers around the world. Often extroverts by nature, many gallerists got into the sales side of this business precisely because of its deeply ingrained social aspects—the jet-setting to art-market capitals, the in-person reveals of a canvas an inch from a collector’s nose, and then the handshake deal closed over backslapping cocktails.

That world no longer exists. We’re now dealing with the fact that many market figures spent years building up an infrastructure based on human contact, and avoided building out the infrastructure needed for virtual engagement.

Now, online viewing rooms are all we’ve got—and if you don’t have one, you need to build one, fast. Outfits lacking the firepower of mega-galleries, having waffled on spending years of energy and untold amounts of build-out fees, have now had to—and I’m borrowing a term from the tech community—“bootstrap” their digital portals. Fairs such as Art Basel and Frieze are providing galleries with “booths” at online “fairs” to peddle their wares, but such “events” happen just a few times a year. And so galleries are now in the midst of building bespoke in-house spaces themselves, from scratch.

“This Happened Very Fast”

Asked whether he had ever considered, pre-lockdown, building an online viewing room, Di Donna replied, “not really.” But on March 10—nearly a week before New York shut down its bars and restaurants, when galas were still being held, and on the day President Trump told senators “we’re prepared, and we’re doing a great job with it, and it will go away”—the gallerist had an inkling that maybe his late-March show would not get the grand Upper East Side opening it deserved. So he got to work.

“This happened very, very fast,” he said. “It’s been a company-wide effort, my whole team has been working on it, fine-tuning.”

The product is, like the gallery, stately, elegant, and relatively demure. An email address is needed to enter. Prices are not listed, though pieces that are spoken for get adorned with a red dot. (At the time of publishing, there was one dot in place.) What could not have been achieved in the real world is the section devoted to Viera da Silva works in major institutions, with pieces from the Guggenheim (shut down) and the Pompidou (on lockdown) and the Tate Modern (ditto) on “view.”

The online viewing room for Tennis Elbow, made to look like the gallery’s sidewalk-facing window at the gallery in Tribeca. Photo courtesy The Journal Gallery.

Like Di Donna, other dealers are striving to create online portals that capture the distinct essence of their IRL brands. The Journal Gallery has worked to develop a virtual home for Tennis Elbow, a project that gives a show to one artist per week, anchored by a single work in its Tribeca window that can be seen from the street. Works are no longer actually out in the window—sorry, downtown social-distancers. But they’re present in the gallery’s new viewing room.

Gallery co-founder Michael Nevin said that there was already an online aspect to the project before lockdown began: those who have a membership to Tennis Elbow (it’s free, but members must be approved by the gallery and agree not to flip any purchases for two years) had been offered the works on email 48 hours ahead of the public launch.

Now, there’s just a digital home base, too. What’s more, Nevin will donate 10 percent of sales through the room to a trio of charities: Food Bank for New York City, CityMeals on Wheels and No Kid Hungry.

“The online sales, the online business, it’s kind of a misrepresentation,” Nevin said. “The gallery’s still rooted in what we’ve always done. if you go on these online viewing rooms and it says click to inquire, it’s not that different from offering works on email. You’re presenting things online but you’re still selling in the old way.”

Similarly, Gavin Brown said the current crisis spurred him to launch into a blistering few weeks of breakneck development on a viewing room that will be ready to launch Friday. A percentage of the profits will be donated to five organizations—the Studio Museum Fund, Harlem United, NYC Health + Hospitals Donation Fund, UNICEF Italia, and Comunita di Sant’Egidio—and Brown said it’s an opportunity to switch up the programming a bit to match the new online atmosphere.

“It’s a different ‘space’ to the gallery proper,” Brown said in an email. “So it offers different possibilities.”

Skepticism Abounds

As recently as a month ago, the gallery model was still focused on physical locations—and Bill Powers thought he’d found the perfect one for Half Gallery when he signed a lease last year at a former Korean friend chicken joint in the East Village. Powers opened Tanya Merrill’s first New York solo show February 29, and by March 13, it was closed. He had to quickly put together an online viewing room, something he hadn’t considered doing before. He’s still skeptical.

“We’ve had an online viewing room up since the last week in March, but the online viewing room thing—unless there’s some other facet—it’s gonna get played pretty quick,” Powers said. “Short term, it’s a good fix, but after a month of that, people are gonna get a little tired of it, unless there’s something more dynamic about how the work’s presented.”

The Half Gallery space on E. 4th Street and Avenue B, with Tanya Merrill’s show installed inside. Photo courtesy Half Gallery.

His attempt at dynamism is a risky one—in addition to outfitting the online viewing room, he’s going to install a brand new show in the gallery, so passersby can get some fresh cultural offerings through the floor-to-ceiling windows while walking six feet apart. Standing there, they can access the online viewing room on their phones, and immediately get an audio guide on what their looking at, and a portal to buy.

“If you can see something in person, and click and hear a little 20-second content on the work, that’s approximating going into a gallery and having the dealer walk you around the show,” he said.

The first show will be called “Under Glass” (…get it?) and feature works by Merrill, Richard Prince, as well as new roster addition Anna Park, a young artist who counts KAWS as a collector. He expects the show to open in a few weeks IRL (through glass) and online.

(Powers hastened to add that he did not want to endanger anyone while installing the show; he and his handler have both been self-isolating.)

Driven by the Artists

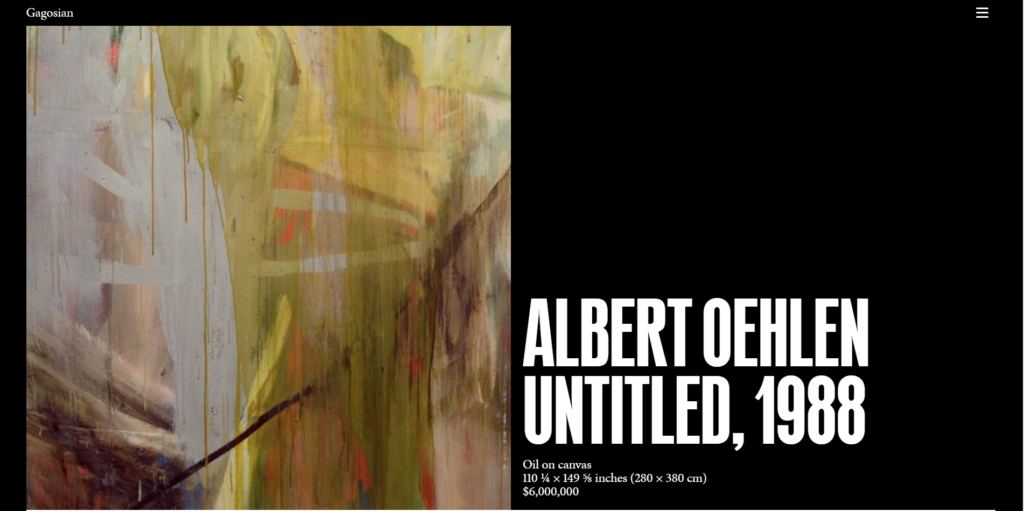

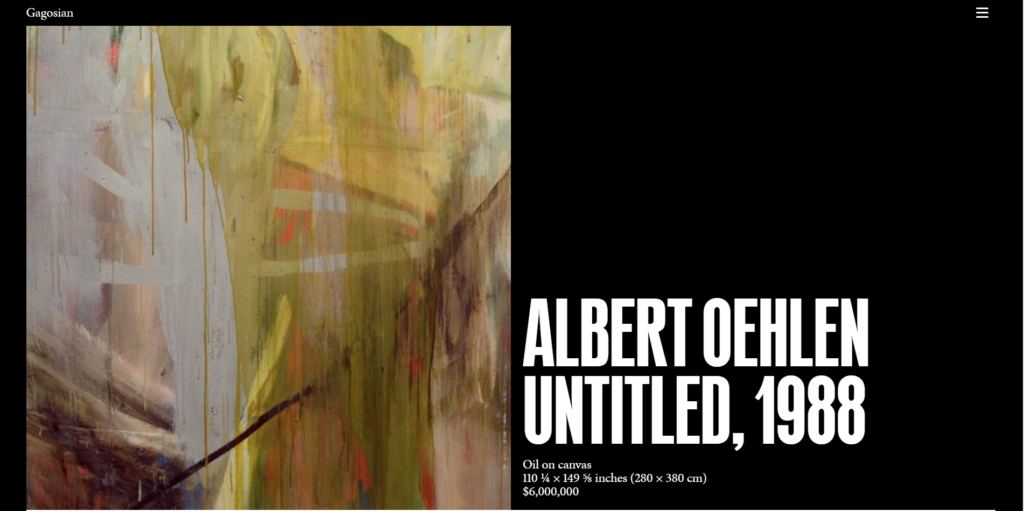

The world’s biggest galleries had the resources to launch online viewing rooms long before they were forced to close their physical locations. Early adopters include David Zwirner, Pace, David Kordansky, and Gagosian, which at the time of the crisis had more brick-and-mortar locations than any gallery on earth. In March 2018, Gagosian made an online viewing room for a work by Albert Oehlen, offered for a price of $6 million, more than the artist’s auction record at the time. The gallery gave collectors a full week to make an offer, hoping to find a buyer in a matter of days. Instead, it sold within three hours, to a collector who had never seen the work.

The mega-gallery online viewing rooms were originally designed to work in tandem with actual sales made out of fair booths and brick-and-mortar spaces, but the crisis has forced even the world’s most successful galleries to adapt. This week, Gagosian is launching Artist Spotlight, a series of one-week presentations of the brightest stars on its storied roster, that will combine a feast of content—written profiles, filmed video material, playlists and movie recs from the artists—with a sales portal that will let collectors buy one work per week, available for a period of 48 hours.

Screen capture of Gagosian’s third online viewing room, devoted entirely to a single Albert Oehlen painting.

Sam Orlofsky, the Gagosian director quarterbacking the mega-gallery’s online efforts, said the idea came out of triage meetings where executives brainstormed a plan for exhibitions that could appease the dozen artists whose shows at outposts around the world were in jeopardy. It was clear instantly that some outside-the-box thinking would be required.

“The artists were extremely anxious,” Orlofsky said. “They saw the writing on the wall and they were looking for some leadership from us, saying, what are we gonna do about my show? The most extreme thought alt is to simply move the shows online, but we didn’t want to do that—that thought lasted about three seconds.”

Instead, a completely new slate of programming emerged, where the sales portal—with just one work each week, to keep supply of in-demand artist sky-high—would be combined with the publishing arm of the gallery, which has grown increasingly important in the social distancing era.

The first Artist Spotlight is Sarah Sze, who was set to have a show open at Gagosian’s Paris outfit the day after lockdowns were enforced. And the regular online viewing rooms will still be “opening” in May and June, pegged to what used to be the now-moved dates of Frieze New York and Art Basel. Rather than focusing on primary-market work, such rooms will offer secondary works, primary market work from gallery artists who don’t have immediate shows coming up, and other inventory.

Clearly, Gagosian is betting that collectors will be still be buying via keyboards for the long haul. There is Artist Spotlight content scheduled to run into July. If the other galleries want to keep up, they’ll need their own rooms—and then some.

“We’re going to be open-minded and flexible about rolling out more initiatives,” Orlofsky said. “I don’t think the online viewing rooms and the Artist Spotlight represent the extent of what you’ll see from us over the next few months.”