Art Fairs

Alternative ‘Seven’ Fair Pokes Fun at Art World Elite

It's both a clever exhibition and a smart sales platform.

It's both a clever exhibition and a smart sales platform.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

Installation shot “SEVEN-ish: Seriously Funny.” Courtesy of Pierogi.

Humor, which Mel Brooks defined as “a defense against the universe,” is not just for psychic protection these days. For SEVEN, the original alt-art fair, it also provides an important measure of hilarious offense. The current iteration of this rebellious show, titled “SEVEN-ish: Seriously Funny,” kicked off Frieze Week last Friday. The joint effort demonstrates that galleries can band together to create both a clever exhibition and a smart sales platform. Seriously.

Launched in Miami in 2010 as an “art fair alternative” by seven galleries from New York and London, SEVEN was founded as a collaborative, art-centric riposte to the increasingly corporate and booth-driven format of international art fairs. In emphasizing the idea of an exhibition rather than an art mall, SEVEN has featured an evolving roster of established dealers over the years.

The current edition presents artists from Anton Kern Gallery, Fredericks & Freiser, Greene Naftali, P•P•O•W, Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, as well as organizers Postmasters and Pierogi.

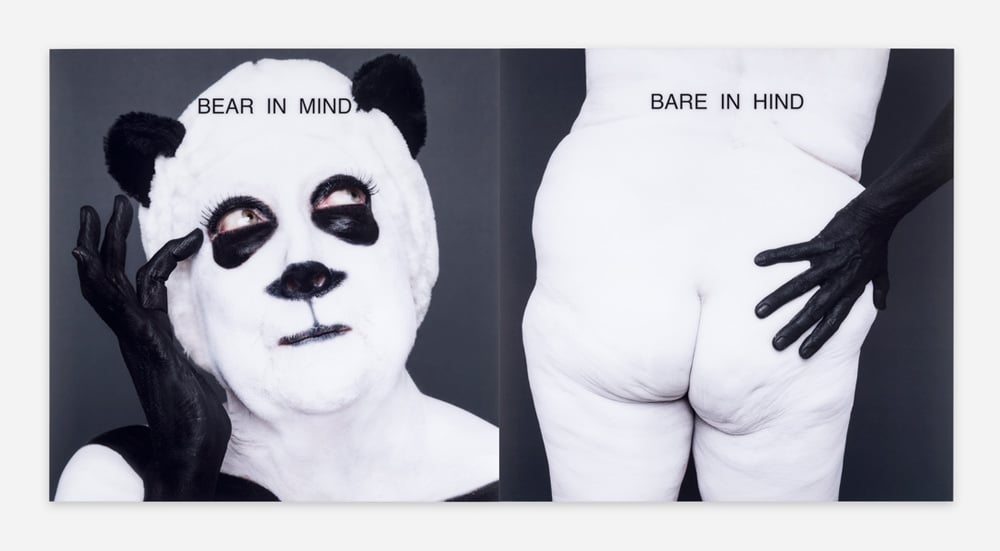

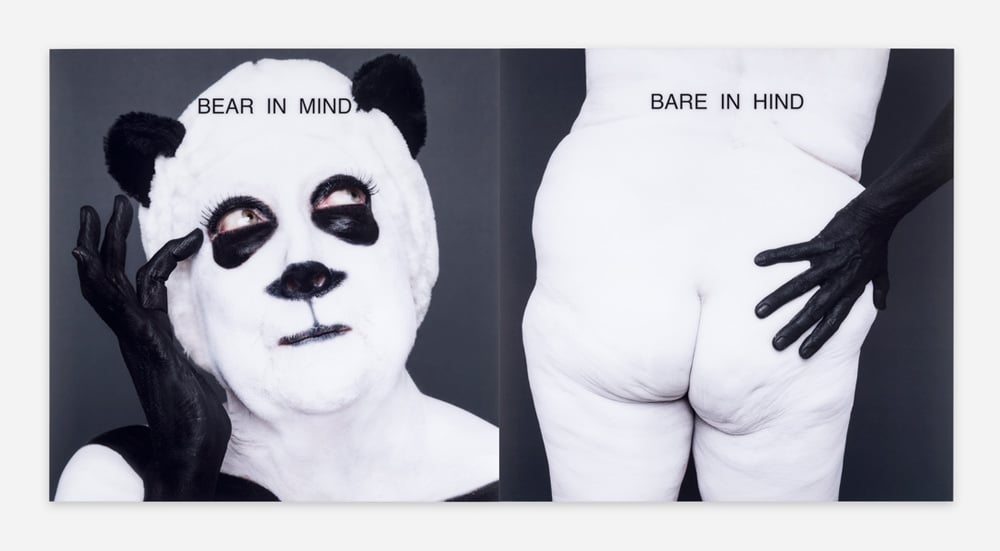

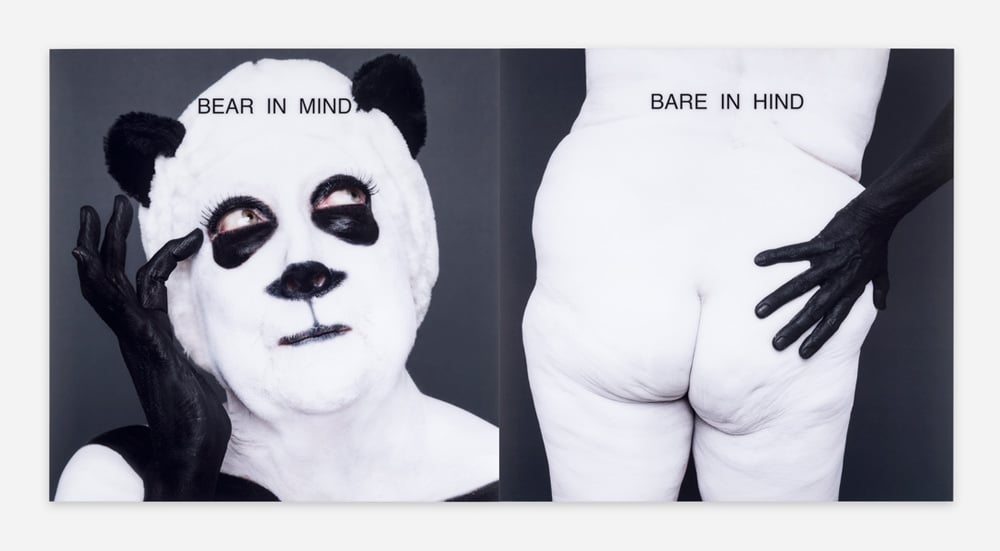

Martha Wilson, Bear in Mind/Bare in Hind (2014). Courtesy the artist and P•P•O•W.

This year’s venue for the event is again The Boiler, Pierogi’s longtime Brooklyn project space. Located in the heart of what was once artist-populated Williamsburg, the large-ceilinged industrial building now sits awkwardly amid a growing gathering of Bro culture—a grouping of young white males the likes of which has not been seen since the last Bud Light “Whatever Party”. Fittingly, Comedy Central’s “Broad City” has pegged the Murray Hill-like nabe—which abuts Greenpoint’s Berry Park—“Berry Hill.”

New York and the art world’s changing demographics are partly why entering The Boiler this week feels like such a salutary change of pace. Far from the local crush of “Most-Dope” t-shirts and the Upper East Side drollery of Maurizio Cattelan’s 18-karat-gold toilet, veteran artists Eleanor Antin, Jen Catron & Paul Outlaw, Gary Panter, Shannon Plumb, David Shrigley, Michael Smith, and Martha Wilson enact the kind of creative stunts George Orwell once labeled “significant mental rebellions.”

“SEVEN-ish” brings together a group of artworks that respond to—or that in some cases anticipated—the city’s relentless mental gentrification. In turn, the best of these paintings, photographs, installations and videos deliver counterpunches that, at times, feel like full-blown attacks of Tourette syndrome.

Shannon Plumb, “Paper Collection” (Video still), 2007. Courtesy the artist and Pierogi.

Take, for instance, Jen Catron and Paul Outlaw’s kinetic Spaghetti Machine Monument (2016). A massive bowl of rubber noodles and moving serving tongs, the sculpture’s loquacious subtitle does even more heavy lifting than the work’s actual mechanized parts: “We considered making an elevated room that addresses belief and our current existential crisis but then decided what’s the point let’s just make this giant spaghetti sculpture.” This is a Claes Oldenburg sculpture with a Damien Hirst-length title that packs the satirical ire of a John Oliver screed.

Elsewhere, Martha Wilson—whom Holland Cotter once called “one of the half dozen most important people for art in downtown Manhattan in the 1970s”—offers up a C-print of her face and wrinkled bottom in Panda bear makeup; the work, titled Bear in Mind/Bare in Hind (2014) portrays the bare facts attendant to a woman artist “having fun with being an old lady.”

Shannon Plumb’s film Paper Collection (2007) channels Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin in a silent movie spoof of the high anxiety surrounding runway fashion. And Michael Smith’s 1996 sad sack video of a not-so-young-man celebrating his nomination to become a model Jaycee—a framed letter is also displayed proposing “Mike” join the Outstanding Young Men of America—nearly morphs into a Matt Groening cartoon (ditto for Williamsburg’s newest outstanding young men).

Michael Smith, “OYMA (Outstanding Young Men of America)” (Video still) 1996. Courtesy the artist and Greene Naftali.

Other artists in “SEVEN-ish” also poke fun at their semi-marginal status as established if less-than-blue-chip-artists, while bemoaning the culture’s general lack of critical consensus—cue Shrigley’s ink on paper vignettes of twisted logic. A show rather than a fair, this farcical gathering of artists and dealers reminds us that you don’t need the biggest tent in the city to put on a good show; a couple of really smart, funny jokes will do.