Art dealers, auction executives, and advisors are scratching their heads, trying to make sense of the surging prices for emerging artists and the relative lack of enthusiasm for the market’s usual golden geese, the established names in Modern and contemporary art whose paintings and sculptures have, over the past decade, become investment vehicles for the mega-rich.

“You feel lost,” an art dealer told me in a hushed voice at a Phillips preview this week. “There are all these new buyers and they are shifting the market. I even heard that the Macklowe is dated taste!”

The Macklowe, of course, refers to the Macklowe Collection, the most highly anticipated sale of the season, which is estimated to bring in more than $400 million at Sotheby’s on November 15. The 20th-century treasures by the likes of Mark Rothko, Alberto Giacometti, and Cy Twombly were amassed over five decades by the real-estate tycoon Harry Macklowe and his museum trustee ex-wife Linda. Its sale was court-ordered as part of the bitter divorce between the two octogenarians.

There’s no denying that the collection is among the most significant postwar and contemporary troves ever to come to market. Viewings of the works at Sotheby’s have attracted thousands of people: 4,000 in New York in just one week, and 5,000 in London last month.

Giacometti’s Le Nez and Warhol’s Nine Marilyns. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Showtime for the Macklowe sale is just around the corner. The estimates are higher than the market has seen in years: Rothko’s No. 7 is $70 million to $90 million; so is Giacometti’s sculpture Le Nez. Twombly’s 18-foot-wide painting of peonies may fetch $40 million to $60 million. All are guaranteed to sell; the question is how high they will fly.

“Their collection epitomizes when they bought and what was the taste,” said Morgan Long, senior director of the Fine Art Group, an advisory firm. “And the taste has definitely shifted.”

Cy Twombly, Untitled (2007). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The biggest change is a focus on artists who’ve been long overlooked.

“When the Macklowes were buying these things, there weren’t that many female artists that were considered to be in the ranks,” Long added. “They’ve got a Jackson Pollock, but were they ever considering Lee Krasner back when they bought the work in 1999?”

Change has been in the air for a few years. Sales have fallen dramatically for classic postwar and contemporary names like Rothko and Christopher Wool, as collectors, curators, and speculators shifted their attention to female artists, artists of color, figures like Banksy, who are considered outside the establishment, and, of course, NFTs. Banksy’s auction sales reached $133 million in the first nine months of the year, surpassing Monet and making him the fourth best-selling artist, after Picasso, Basquiat, and Warhol, according to Artnet Analytics.

The new dynamic was unmistakable at Christie’s 20th and 21st century sales this week. On Thursday, Gerhard Richter’s abstract painting drew just one bidder, the guarantor, hammering at $25 million. Ditto Ed Ruscha’s Ripe, which went for $18 million. Both prices just reached the low estimates.

Beeple, HUMAN ONE (2021). Courtesy of Christie’s.

A few days earlier, three paintings by Wool, once a market darling, also went to their guarantors with no competitive bidding. Meanwhile, Beeple’s first sculpture sold for $29 million, doubling the estimate, and works by younger artists like Hilary Pecis, Issy Wood, and Rashid Johnson obliterated their estimates and spiked bidding frenzies.

Many of these works were acquired by Asian collectors, who’ve become a major force in the market.

“The numbers just multiply,” said Kevie Yang, a senior vice president at Phillips, referring to new buyers. “Younger collectors are still accumulating wealth and building their identities as collectors. They want to collect works by their contemporaries. It’s probably like the Macklowes, who were collecting art of their time—it’s what speaks to now.”

Put simply, Yang said, they want to find the next Basquiat.

And so, they bid up emerging art with an intensity that alarms—and dismays—the stalwarts in the trade.

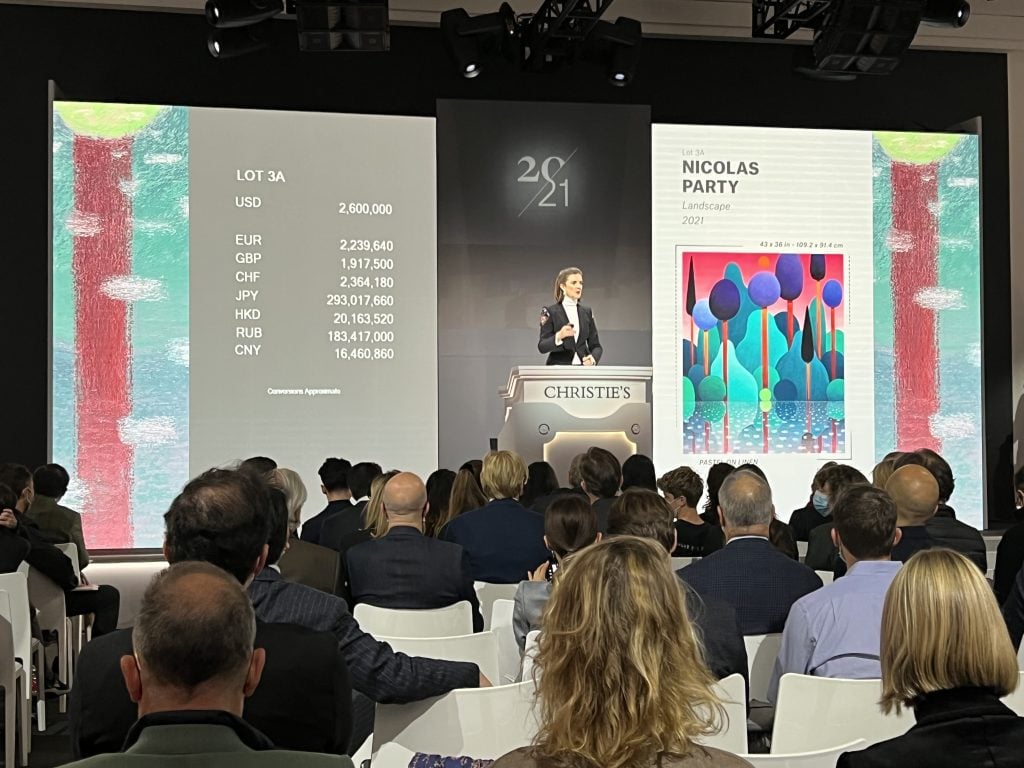

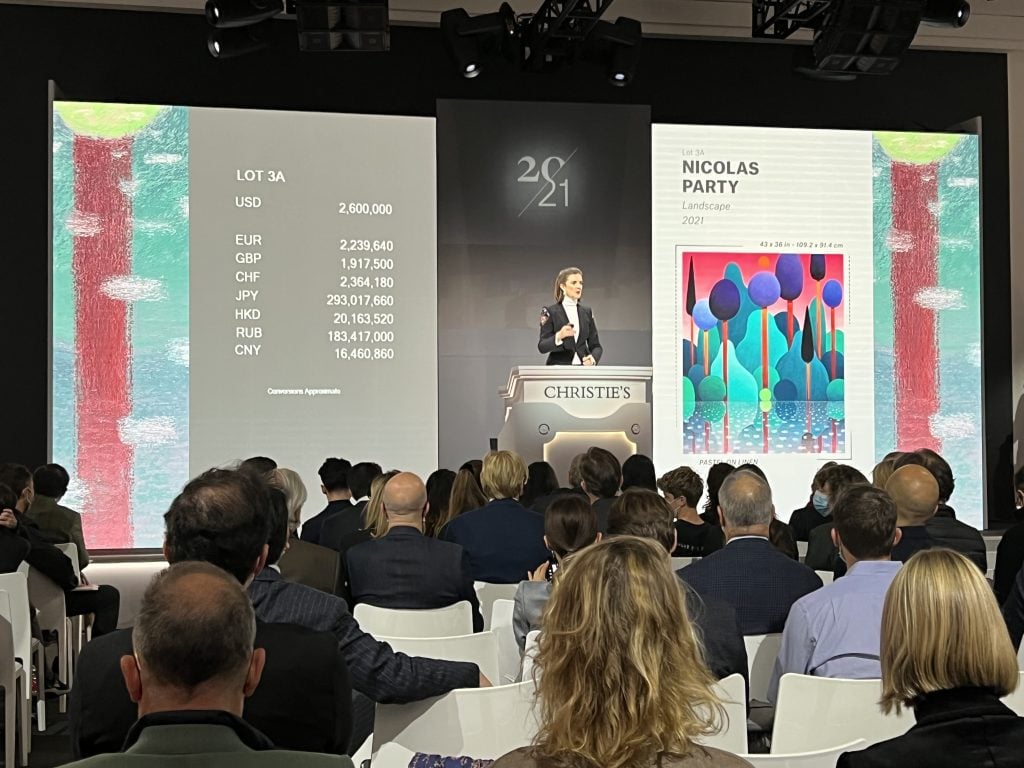

“This new market is led by people with a lot of money and no knowledge,” said the dealer browsing Phillips’s preview. “They are willing to pay $3 million for Nicolas Party! Maybe I don’t understand anything anymore.”

Auctioneer Gemma Sudlow helms the 21st-century evening sale at Christie’s New York on November 9. Photo: Katya Kazakina.

Accordingly, the auction houses are adapting their sales pitches. In the past, specialists would position emerging talents in the context of their great predecessors—but the premium on the new seems to have shifted the balance.

A painting by Georgia O’Keeffe was recently described by Elizabeth Goldberg, senior specialist in American art at Phillips, as looking “so contemporary in the context of all these young painters,” during a conversation with a client. “It’s 1939, yet it fits right in.”

Auction houses, which benefit from the sudden demand, are quick to downplay the shift. “It’s not so much taste change as taste expansion,” said Robert Manley, deputy chairman at Phillips.

Brooke Lampley, Sotheby’s chairman and global head of fine art, acknowledged “a perception of shifting tastes,” but offered another way to look at it.

“It’s a question of supply,” she said. “What was available during the pandemic for collectors to buy was great art from living artists [on the primary market]. The incredible demand for those works then of course promotes their resale at auction, because there is a clear access issue around primary market works. Prices are promoted by this dynamic.”

Then, there is the matter of quality. The best material, Lampley said, is “what attracts collectors in the widest spectrum,” regardless of when it was made.

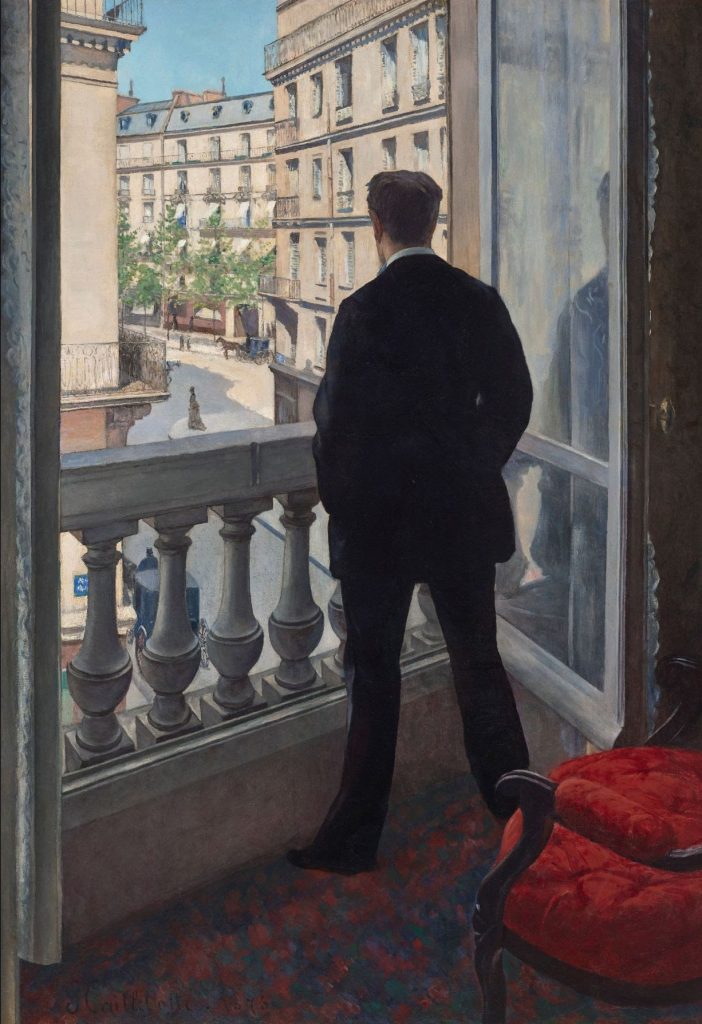

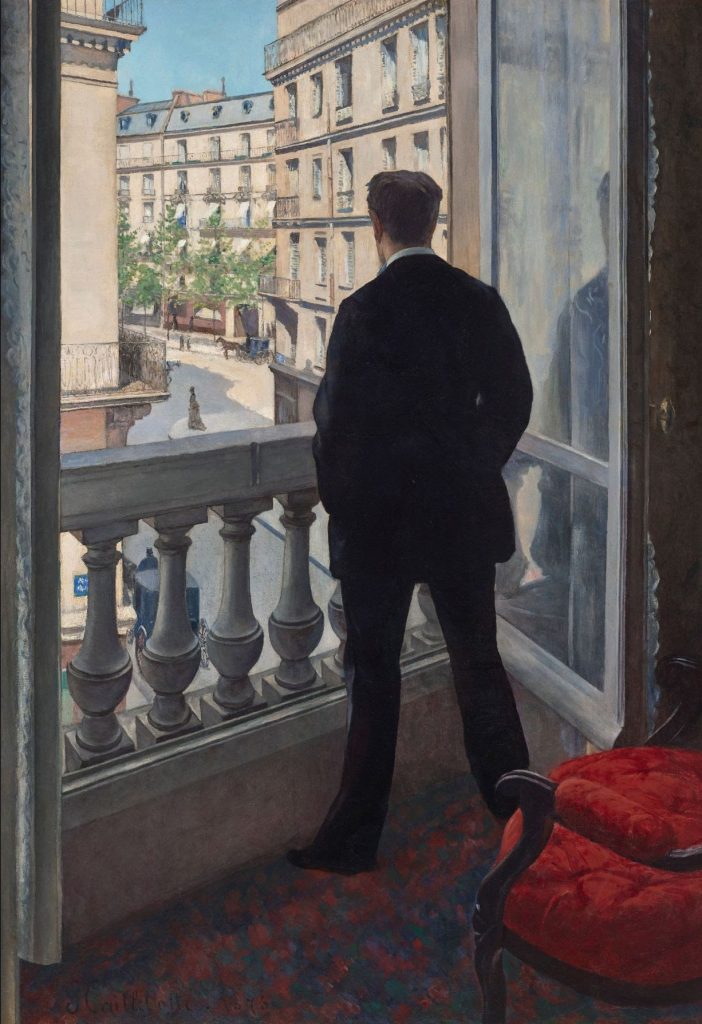

Gustave Caillebotte, Young Man at His Window, (1876). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

Christie’s sale on Thursday of the collection of Edwin Cox, who died last year, proved Lampley’s point, with all 23 top-flight, fresh-to-market works of Impressionist art finding buyers, and three paintings by Van Gogh alone fetching $153.9 million. The Getty Museum bought a masterpiece by Gustave Caillebotte, Jeune homme à sa fenêtre (Young Man at His Window) (1876), for $53 million.

Sotheby’s is working to ensure that the Macklowe material is just as well advertised to potential clients, sending the works on tour to Taipei, Hong Kong, London, Los Angeles, and Paris before they arrived in New York. It’s also pulling out all the stops to encourage a younger generation to view the material as cool. This week, the house hosted rapper A$AP Ferg and a flock of influencers to take photos with Sotheby’s chief executive officer Charles Stewart—and post them amply on social media.

That’s the strategy these days, Lampley said: “It’s people coming in and seeing the collection and telling all of their friends and acquaintances that it’s a must-see because it represents the very best of what the art market has to offer.”