Events and Parties

Will Sotheby’s Again Fall Victim to Corporate Hubris With Dan Loeb, Tad Smith Takeover?

The corporate suits are back in charge. Are these greedy bastards any different?

The corporate suits are back in charge. Are these greedy bastards any different?

Eileen Kinsella &

Benjamin Genocchio

It all feels like a case of déjà vu.

For anyone who’s been involved in the art world for more than fifteen minutes the recent “corporate takeover” of Sotheby’s sounds a depressingly familiar note.

Didn’t we just leave that party? In case you’ve forgotten, the last corporate raider to take over Sotheby’s and promise to raise profitability, cut the waste and boost the stock price ended up in jail.

Um… yeah.

So who’s talking about that? Well, nobody.

Sotheby’s New York City Headquarters

In fact the appointment of Mr. “I’m being paid a Tad too much” Smith as new CEO of Sotheby’s was mostly greeted in the business pages as a welcome and even long overdue step forward toward good governance and sound management at the auction house (see: Sotheby’s Names Tad Smith As New CEO and Sotheby’s CEO William Ruprecht Pushed Out). It’s about time, the finance suits believe, we got these art people out of the art selling business. Leave it to the professionals, people who make a living, that is, buying up companies, carving up their assets, sacking staff, artificially inflating the stock price and then moving on to a better, bigger Greenwich Conn. home address.

Shares of Sotheby’s stock saw a small spike after the news was announced early Monday morning. Money likes money, I guess. Art Market Monitor’s Marion Maneker talked about the notoriously difficult business of running auction houses in a post on Quartz.com with the lengthy title: Someone Should Tell Dan Loeb that Tad Smith will never turn Sotheby’s into the next Gucci and Dear Dan Loeb, We’re Doing Just Fine, Sotheby’s.)

Other than that, nobody really wanted to mention the giant elephant in the room: corporate types simply don’t understand the art world and the art business, which they can’t model, and think somehow they can transform it into a species of the luxury goods business—or, in this case, some sort of entertainment franchise much like the one that Tad Smooth (I mean Smith) was managing before he was seduced to Sotheby’s with, well, an offer of far more money than the previous CEO Bill Ruprecht, who Dan Loeb considered overpaid. Um, okay, how does that compute?

Courtesy: Yahoo Finance

You have to wish Mr. Smooth luck, and I do, but as mentioned this isn’t the first time that corporate-minded leaders have taken over Sotheby’s, the world’s oldest auction house and one half of the art world’s biggest share of the auction market. Let’s dig back into that history, just a little, so that Dan Loeb, Tad Smooth and their boardroom buddies can have all the relevant and pertinent information at their disposal.

Two decades ago, in 1993, corporate hubris and a desire to shift from the socially marginal business of real estate and shopping mall development to something more prominent and socially acceptable prompted a parvenu named A. Alfred Taubman to take over Sotheby’s. Five years later, he took the company public. Yes, before the corporate types set in on the place Sotheby’s was doing just fine as a private company.

Though well-heeled art world insiders grumbled at grubby Taubman’s shake-up of their staid, clubby world, no one could deny he secured some victories and in a way transformed the auction business. He introduced it to high finance, leverage, and wildly excessive risk. He made lots of fast money for people but he also ultimately lost a lot of money. So it goes in the real estate investment game—you bet big.

He also pushed the auction world towards popular culture and fame and glamour. He scored success with celebrity sales such as the estate of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis and the Duke and Duchess of Windsor in the mid-1990s that brought a new crop of aspiring middle class buyers through the doors.

Publicity came too and auctions became media events. It didn’t matter; nobody in the room was bidding. It mattered to the media who covered it with a voracious interest in the nexus of power, money, and fame.

Sotheby’s new CEO Tad Smith.

The problem?

Well, behind the scenes both Sotheby’s and Christie’s (which sought to match them, following Taubman’s aggressive corporate maneuvers) were “hemorrhaging” money, as press reports described it, by promising sellers commission-free deals, multimillion dollar low-interest loans, elaborate promotional dinners and parties, and costly “vanity” catalogs among other pricey perks. Irony of ironies—charm, glamour, and the lure of hands-free excessive spending was how art had always been sold at the big auction houses. Times had clearly changed but the methodology of selling remained the same. Losses piled up.

To stem the tide, Taubman and his counterparts over at Christie’s cooked up a clever little scheme to fix commissions they paid to collectors on art consignments as a way of guaranteeing revenue on sales. The problem was that it was illegal and actually sort of stupid. Pride, arrogance, feelings of invincibility were to blame.

As Carol Vogel reported in the New York Times, in 2001, following Taubman’s conviction and one-year prison sentence: “Seldom has a scheme seemed to yield as little, in the end, for its participants as this one has.”

Sotheby’s CEO Diana “Dede” Brooks was given house arrest and a lengthy probation term as well as ordered to pay fines. Christie’s Sir Anthony Tennant refused to come to the US to stand trial and British law, under which price-fixing is considered a civil not a criminal offense, does not support extradition.

Along with having to pay hundreds of millions of dollars in legal settlements, lawyer fees and collusion fines, Sotheby’s reputation was heavily damaged by the details that emerged at Taubman’s trial: news of backseat limousine meetings at JFK airport between Brooks and Christie’s CEO Christopher Davidge (the latter also got off scot-free and later turned over stacks of documents to US prosecutors); embarrassing concessions to powerful consignors like a $14 million guarantee to Pamela Harriman regardless of the outcome of her sale; and waiving the seller’s commission on the 1996 Onassis sale up to $10 million. So much for the rigor and business-minded focus of corporate leadership at auction houses.

There was also the ugly finger-pointing that went on between Brooks and Taubman as their scheme was uncovered. Brooks said Taubman was the mastermind behind the scheme. When she testified at his trial, she recounted how he once told her “You’ll look good in stripes,” in reference to a possible prison sentence.

But it gets better.

Anyone seen the recent announcement of a new collaboration and joint venture between Sotheby’s and eBay? Sure you have. It’s the future of the auction business. Yeah right.

Another black mark on Taubman and Brooks’ tenure was the first costly, ill-fated eBay Sotheby’s venture that lasted just a few years, before it was terminated in 2003 after costing close to $100 million. Yes, our good corporate governors flushed that colossal amount (belonging to shareholders) down the toilet.

Sotheby’s and eBay have recently decided to venture down that path again (see: Weighing the Pros and Cons of the Sotheby’s eBay Partnership and Sotheby’s and eBay Unveil Details of New Partnership—Will It Work?). Nobody believes it will work. But I’m sure Dan the Man and Mr. Smooth will get it right.

What is interesting to remember, amid all the recriminations over Sotheby’s current stock price and the lack of core management expertise at the company, which is true, is that Bill Ruprecht’s appointment in 2000 was a reaction against the profit-driven, share-price focused, corporate overreaching at Sotheby’s. He was the last man standing after the place was gutted, one of the people left at the company untarnished by Taubman’s criminality who actually understood how art and other high priced objects were bought and sold. He took the reins, promised to learn from past mistakes and went back to business.

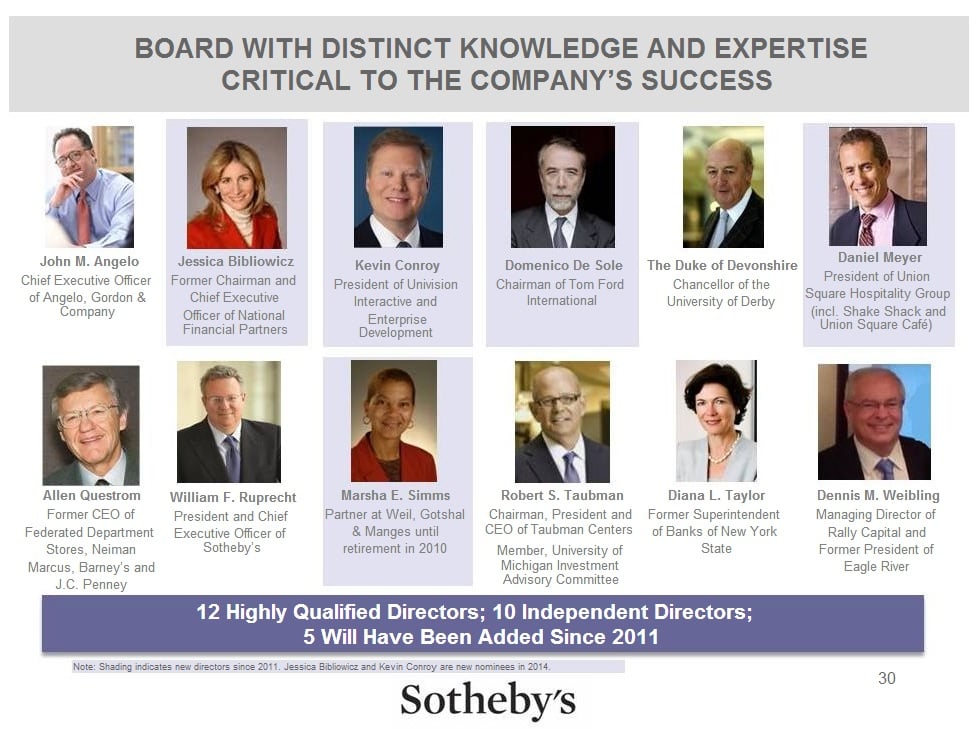

Sotheby’s board as presented in slide show response to Daniel Loeb lawsuit.

Fast forward to today and the acrimonious triumph of the activist shareholder Dan Loeb, whose win looks a lot like Taubman’s bold play for the business 20 years ago. Loeb wants control, yes, but of a different kind, and is on a mission to appoint people who he believes will run the company how he believes it should be run: he pushed for the appointment and wider leadership role assumed by former Gucci executive, now Sotheby’s chairman, Domenico De Sole, and now the appointment of Mr. Smooth, former CEO of Madison Square Garden. With these two appointments, Sotheby’s has returned to pure corporate control and, as an aside, it should be noted, the use of pure corporate language like multiple revenue streams, cost-cutting, increasing profitability, and a five-year growth plan aimed at enhancing shareholder value (see: Dan Loeb Triumphs, Will Join Sotheby’s Board).

According to financial filings made with the SEC, Mr. Smooth’s base salary is $1.4 million and his “target annual bonus opportunity will be 200 % of his annual base salary.” Mr. Smooth will also receive “long-term incentive award opportunities” in the form of restricted Sotheby’s stock. Is there an art to improving profitability while selling multimillion dollar paintings? If so, then Mr. Smooth better be the Leonardo da Vinci of corporate management.

“While the auction business is new to me,” Mr. Smooth said in a brief conference call on Monday morning last week, “I think you’ll find me a quick study.”

Study?

Well, I guess it’s a good thing that he’s admitting that he has a lot to learn. If you don’t mind Tad, I’d like to recommend that first up on the list of books you need to read and study is Christopher Mason’s The Art of the Steal, about the price-fixing scandal and the years of “shareholder value-driven” corporate excesses at Sotheby’s and Christie’s.

Welcome to the art world.