Art Fairs

Five Star Artworks That Stole the Show at the Inaugural Frieze Los Angeles

From scenery-chewers to smoldering powerhouses, these artworks shined brightest in the fair's spotlight.

From scenery-chewers to smoldering powerhouses, these artworks shined brightest in the fair's spotlight.

Andrew Goldstein

While not a few people headed to the inaugural Frieze Los Angeles in the hopes of seeing celebrities in the aisles, there were plenty of stars on the walls too. Satisfyingly compact (make that: god-thankfully compact), the fair had a healthy share of extraordinary artworks, even if—as an education fair for LA’s elite—it had some remedial 101-material mixed in with the masterclass. In any case, here are five of the most interesting works on view in the big tent.

There is so much to think about in this magisterial photograph by Catherine Opie that it’s not even funny. A portrait of almost colossal regality, it portrays Thelma Golden, the director of the Studio Museum in Harlem, and her husband, the fashion designer Duro Olowu. Golden, who is wearing one of his designs (as she habitually does), happens to be one of the most fascinating figures in the art world today—currently the most powerful African American museum director in the country, she has been a guiding force in raising the visibility of black artists, she is building a new 82,000-square-foot museum in Harlem, and, after that is completed, she is the odds-on favorite to succeed Glenn Lowry as director of the Museum of Modern Art.

Here, in this photo from 2017, look at how Opie poses her subjects. Seated, confidently regarding at the viewer, Olowu is manifestly present, embodied; Golden, on the other hand, is standing, literally resplendent as light gleams off her finery, gazing off to the distance with an unearthly expression—as if transfixed by an angel, or a ghost. It’s a photograph but it might as well be a movie, so rich is the plot.

Lawrence Weiner was born in the Bronx, and John Baldessari was born in National City, California, and together they occupy the pantheon of conceptual art as representatives of their respective coasts. Together they also occupy Marian Goodman’s booth at Frieze LA, where the two old friends have collaborated on a joint presentation of their work that is one of the unmissable highlights of the fair—and a symbol, in a way, of the way the fair is trying to merge the LA and New York art markets. (You can just step out to the fair’s New York-themed backlot of another, more overt symbol of this.)

A sequel of sorts to a previous collaboration the artists did at PS1 in the 1990s, the installation consists of one of Weiner’s signature verbal “sculptures” (he has said he considers himself a sculptor) from 1992 on the wall overhung with two new diptychs from Baldessari’s “Hot & Cold” series. Those paintings contain still additional layers: showing the ecologically poignant pairing of an iceberg and a volcano, the present text taken alternately from Ernest Shackleton’s narrative of his voyage to Antarctica and from Sunset Boulevard, Baldessari’s favorite film.

The collaboration was a hit at the fair, perhaps because it constitutes the conceptual-art equivalent of that classic Hollywood genre: the buddy movie.

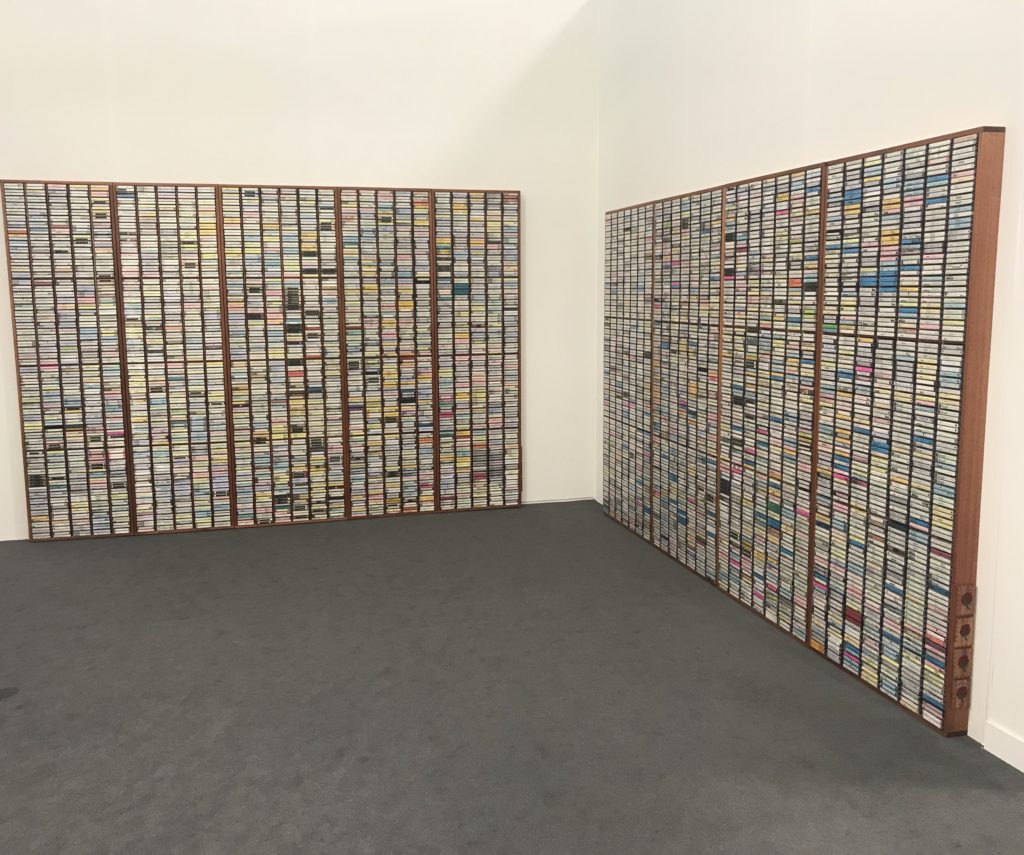

One of the most talked-about works at the fair was also one of the most inconspicuous to the eye, since it doesn’t look like art, really. Consisting of two wall-spanning wooden shelving units stacked with cassette tapes, the presentation looks like something you might have found at a college radio station in the 1980s, but it actually speaks to a music obsession far greater than that: each unit contains a wildly comprehensive (if still partial) collection of over 3,000 Grateful Dead bootleg tapes, recorded between the band’s founding in 1965 to its end with Jerry Garcia’s fatal heart attack in 1995.

The artist, 36-year-old CCA San Francisco grad Mark A. Rodriguez, is too young to have recorded the tapes himself, but he did the next best thing, sourcing many of the cassettes from its network of devoted followers. (He has also worked on a different series with Dead superfan Tom Stack, who spent over 20 years following the band and rose from groupie to its VP of marketing.) Rodriguez has now done four “generations” of this project, each time finding new recordings that he supplements by dubbing tapes from the preceding generation and meticulously re-writing the set lists on their j-cards. As a result, each set contains recordings of diminishing fidelity, but that didn’t deter two collectors—one in LA and one bicoastal—from buying the third and fourth generations sets on view at the fair.

Studio Drift, the Dutch art collective founded by Ralph Nauta and Lonneke Gordijn, has become famous for their extraordinary experiential works, from lanterns that rise and fall from the Rijksmuseum’s ceiling like swimming jellyfish to the “concrete” block that hovered in midair at the Armory Show in 2017 to the choreographed ballet of illuminated drones that flew through the night sky over Art Basel Miami Beach later that year. What they haven’t had are artworks that a collector might be realistically able to buy and take home, which is a crucial way of supporting such experimental work. Now, at Pace’s booth, they’ve hit upon something that neatly encapsulates their technological wizardry in domestically scaled objects.

What they’ve done is taken everyday objects—from a pencil to an LED bulb to a Dyson vacuum cleaner—and deconstructed them down to their constituent materials, then recreated blocks of those substances as little ingots that precisely match the original proportions. This one, for instance, is a bicycle, meted out as playful individual blocks of rubber, polyurethane, steel, aluminum, lacquer paint, acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS), polyoxymethylene (POM), gel, stainless steel, polycarbonate, brass, magnet, and glass fiber. It’s undeniably fun.

Studio Drift, of course, likes to think big, even in such a compact series—so the next thing they do will be an atomization of an airplane.

Technological wizardry certainly has a (growing) place in contemporary art, but leave it to Kerry James Marshall to remind you that old-fashion painting still possesses an uncanny power to leave a mark on the world. This painting yet again demonstrates the artist’s bravura abilities with the medium, but—with its strange, cartoonish head in tutti-frutti colors buried in black—it seems like a new kind of iconography for Marshall. It’s actually a very old one.

It turns out that, when the artist was a child, he was taught the trick of using the letters of a word to draw a picture of what it denoted, and he enthusiastically started filling up notebook after notebook of these drawings—which he now considers to be his first artworks. Here, Marshall combines that technique (using the letters b-o-y to create a child’s head) with another art-game from his youth where you would use crayons to draw a picture, cover it with black paint, and then peel back the paint to create an imprint. No one is going to peel back the paint from a Kerry James Marshall, however, and he has here scrawled the word “black” in black on top of the paint—tying this uncommon, childhood-plumbing canvas, in a way, to his grand overarching project of using painting to put visions of black life front and center in art history.