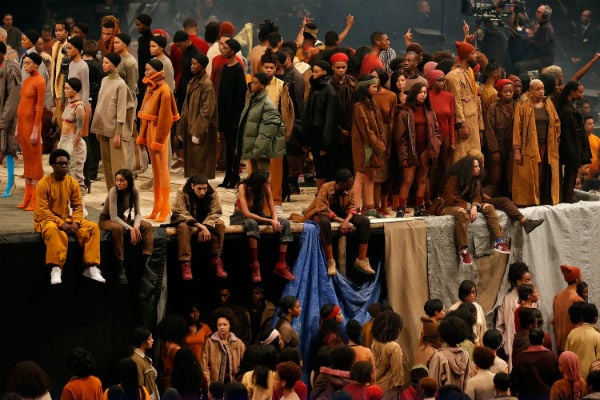

Photo by JP Yim/Getty Images for Yeezy Season 3)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan is opening its new contemporary art initiative, taking over the old Whitney Museum of American Art’s building uptown. Last year, the Whitney developed its own flashy tourist-courting site near the High Line. On the other coast, the Broad Museum in Los Angeles opened its doors last year and Hauser & Wirth is soon to launch its gigantic new space, which the Los Angeles Times compared to a Home Depot.

In scale, the art scene grows and grows.

Yet there is another narrative, running alongside the story of constant growth, that says that art is more and more embattled. Record-breaking crowds at big museums go alongside an overall erosion of the museum audience nationally. The audience for contemporary art grows even as the audience for anything that is not fashionable or of-the-moment is cratering. The humanities and arts education are in crisis, with funding cuts left and right.

And so, depending on the circumstances, you will either find people marveling at art’s new cultural visibility or lamenting its loss of status.

I want briefly to propose a way to think about this double pressure, which can be summed up with this graph:

The exact ratio here is made up. It’s a propaedeutic device.

The blue area, as the label indicates, stands for the art world; the progress from left to right illustrates that it has grown over time, as it surely has. There have been ups and downs, but Diana Crane says in The Transformation of the Avant-Garde, “During the forties, the number of galleries specializing in the sale of contemporary American art was probably around twenty.” A simple glance at the roster of the Armory Show this week shows that we are so far beyond that as to be in a different galaxy.

The red area of my graph is mass culture, broadly defined as Hollywood films, television, video games, Netflix, etc. These industrial-strength alternatives to traditional visual art have grown in prominence as well, in truth much faster. “On average, people spend more than 490 minutes of their day with some sort of media,” one report said recently. That’s more than eight hours (and it’s a conservative estimate).

On October 8, 1911, the New York Times dedicated almost the entirety of its front page to a single breaking news story: “The Cubists Dominate Paris’ Fall Salon.” This reads today as a transmission from another world: It is hard to imagine technical debates within the art scene of another country dominating public discussion in that way, even within its own target audience.

Detail of New York Times front page, Oct. 8, 1911

Image: via Wikipedia

But then, it wouldn’t even be until five years later that the Times first allowed the verb “to film” into its lexicon. The paper then was ready to admit that moving pictures were “broadening the public knowledge, making globe trotters of the stay-at-homes, showing us the wonders of the growth of plants and the development of animal life.” Yet, as art, the paper went on, film would always be a “feeble substitute” for serious theater. In fact, it concluded, “the vogue of the moving picture is surely at its height.”

The following century proved the Times wrong, in ways that so inform our present-day understanding of art that it is hard to step back and take their measure.

In 1972, when the curator and critic Lawrence Alloway wrote his classic Artforum essay “Network: The Art World Described as a System,” he was trying to explain the rise of the modern art world, dating from the 1960s, and the contradictions he saw running through it. He described it exactly in terms of a growth that created a double pressure, from within and without: “Not only has the group of artists expanded in number but art is distributed to a larger audience in new ways, by improved marketing techniques and by the mass media.”

On the one hand, the professional art scene itself grew to take on a new kind of stable self-awareness as “a permanent interest.” On the other, it became an object for the rapacious fields of design, advertising, and fashion to play with. Alloway mentioned “Abstract paintings in House and Garden features on collectors, or the Park Place Gallery photographed with fashion models among the sculpture” as representing a new kind of media presence for art, one that demanded consideration. (Sound familiar?)

Once art took its place in the context of this broader media culture—Alloway called this the “fine art-pop art continuum”—the values art represented changed, becoming more relative. “Thus there exists,” Alloway summed up, “a general field of communication within which art has a place, not the privileged place assigned to in humanism as time-binding symbol or moral exemplar, but as part of a spectrum of objects and messages.”

Eric Hobsbawm, writing about the same period in The Age of Extremes, is less sanguine about what these same developments mean than Alloway. “From the 1960s on the images which accompanied human beings in the Western world—and increasingly in the urbanized Third World—from birth to death were those advertising or embodying consumption or dedicated to commercial mass entertainment… Compared to these the impact of the ‘high arts’ on even the most ‘cultured’ was occasional at best.”

What if we reconfigure my same graph from above to assume that both segments are parts of a whole, that is, if we assume that there is a finite economy of attention in which culture in all its forms competes? The evolution of the same data over time would look like this:

An absolute growth of size can also be a relative loss of status.

A number of phenomena that I have written about recently appear to be manifestations of this two-sided underlying evolution. For example, the number of working artists in New York has grown, even as its growth is dwarfed by the growth of design and film production.

I also thought about this double tension when reading about artist Vanessa Beecroft’s recent collaboration with Kanye West in Madison Square Garden. As Nate Freeman at Artnews put it, the immense spectacle of thousands of fashion models mimicking the disarray of a packed Rwandan refugee camp may have “had more real-time viewers than any work of performance art in history.”

And yet Beecroft herself has ditched both fine art and the persona of the fine artist. She was always kind of a tacky figure, but there was a time she was also associated with the art world’s biggest galleries, Gagosian and Deitch Projects. Now, she has completely subsumed her identity to the Kanye brand, focusing on made-to-order fashion events.

“I like that,” Beecroft told Freeman, “the power of the work, and the power of influencing lots of people, not necessarily the art elite.”

The “art world” has continued to grow exponentially since Alloway’s time. It is big enough that there are people who can, and do, live within it, like the dealers and collectors who find themselves, in Graham Bowley’s words, riding “a worldwide carousel of art fairs from Miami to Hong Kong to Basel to São Paulo” that never stops.

The danger is that it may be so unwieldy and enveloping that it obscures how relatively fragile the ecosystem has become. Better to think art’s continuous scaling up not as a simple triumph, but as part of high-stakes competition for relevance within a media culture that is gobbling up public attention. The Met’s contemporary-art initiative is avowedly about this, competing with their peer institutions for audiences and donors whose attentions are increasingly fixated on the present.

I guess I think of the “art world” as something like a historic resort town. People who don’t want to play by big city rules can escape to it. Rich people love it because it is intimate and easy to circulate in. It is full of colorful characters. It has a servant class.

The outside metropolis has grown more cluttered and cut-throat. So, the demand to get away from the metropolis grows and grows. And the small town thereby grows as well, and loses some of its quaint and historic character.

But it is still a small town. Its infrastructure creaks and is stretched to do things that it was never meant to do, even as it tries to preserve the charms that draw people to it in the first place. Traffic in the Hamptons, I hear, has gotten horrid.