Art Fairs

Meet the Art SWAT Team That Keeps Fakes Out of Europe’s Fanciest Art Fair

We talked to TEFAF's global vetting chairman Wim Pijbes about the fair's new approach.

We talked to TEFAF's global vetting chairman Wim Pijbes about the fair's new approach.

Sarah Cascone

Two days before the European Fine Art Fair, arguably the world’s premier Old Master fair, opens in Maastricht, a squad of elite art historians shuffle from booth to booth. An intimidating 293 art dealers are collectively showing over 7,000 years of art history, and this academic SWAT team is on the ground to weed out any fakes, incorrect labeling, or other mischief before the fair opens to the public.

Vetting, as the process is known, is expensive, invisible, and has recently undergone some major changes at TEFAF. But it remains key to ensuring that collectors can trust in the fair’s offerings and know that they are getting exactly what they are paying for.

Enter Wim Pijbes, a Dutch art historian and the fair’s new global chairman of vetting, a newly established position overseeing both the Maastricht and New York editions of TEFAF.

“The chance that fakes would show up here is very limited, and that they would pass the vetting is almost impossible,” Pijbes told artnet News last week at the fair’s first VIP preview day. “It starts with good dealers, then with good pieces, and ends with vetting.”

As chairman, Pijbes isn’t conducting the vetting himself, but he is there to step in and make a ruling in the event of a dispute. He is the final authority on whether or not a piece lives up to TEFAF’s standards and joins the fair as it looks to standardize its vetting protocols. “TEFAF wanted to have an independent authority to judge and to chair the whole phenomena of vetting,” Pijbes explained.

Previously, Pijbes was director of Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum for more than seven years. He left in 2016 to lead the Museum Voorlinden, a new private museum outside The Hague—a gig that he quit after just three months. In 2017, he became head of the Rotterdam arts foundation Stichting Droom en Daad.

Wim Pijbes. Photo by Vincent Mentzel courtesy of TEFAF.

This year’s edition of the fair sees a major change, as art dealers are now excluded from voting positions on the vetting committees for the first time. They are still involved—”we need their expertise,” Pijbes admitted—but no longer have voting power when it comes to approving or rejecting a work from inclusion at the fair.

“With dealers, you always have the risk of commercial interest,” said Pijbes, noting that a gallery owner selling similar work might have an incentive to set higher prices or upgrade a work of art’s attribution. He says the shift has been well received: “It’s about trust. Trust, transparency, and truth.”

Privately, however, some may have grumbled that dealers’ extensive expertise shouldn’t be overlooked just because of their commercial ties.

“I wouldn’t say its a silver bullet for eliminating conflicts of interest,” TEFAF dealer Andreas Pampoulides, of London’s Lullo Pampoulides, told artnet News. “And dealers can have an insight into works of art that museum curators and university lecturers might not.” He is in favor of adding more non-voting dealers—there were five in 2019—to the vetting committee next year.

And other fairs don’t see dealers as a potential risk. At Masterpiece London and the Winter Show in New York, gallery professionals make up an important part of the approximately 150-person vetting teams.

“Each organization is different. We are always interested in seeing what other high-end fairs do and review our policies with the vetting co-chairs annually,” Helen Allen, executive director of the Winter Show, told artnet News. “We believe that the mix of specialists we have currently works well and we continue to evolve the committee to ensure that we have knowledgeable experts in each field well represented to vet the work at the fair.”

Altogether, TEFAF has 180 vetters hailing from 14 countries. Their ranks include curators and scholars from such esteemed institutions as London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. (In the interest of transparency, their names are printed in the fair catalogue.)

There are specialists in each category, with different experts reviewing the arms and armor, for instance, than those charged with vetting clocks and watches, Precolumbian art, or textiles and wallpapers. There are even different teams covering the different geographic regions for Old Master paintings, splitting up the Dutch, Flemish, and German works from those by Italian, French, Spanish, and British artists.

The vetting committee spends a full two days on the job—which means that galleries have to have their booths set up and ready to go two days before visitors arrive.

The most common issues are with an artwork’s label—here and there, you’ll find booths that have hand-scrawled a correction for an attribution, or some other minor aspect of the information about the work. Nothing, according to Pijbes, was pulled from this year’s edition of the fair.

The vetting committee uses modern technology at TEFAF Maastricht. Photo courtesy of TEFAF Maastricht.

When the vetting kicked off on Tuesday morning, Pijbes’s opening remarks were followed by a quick speech by Rob Erdmann, a senior scientist at Rijksmuseum, which sets up a pop-up laboratory on site at TEFAF each year.

“There are X-Rays and UV scanning and all this state of the art stuff,” said Pijbes. “The experts know what they see, but just in case if they’re not totally sure, these other techniques are available just to have a second opinion.”

He estimates that for 99 to 95 percent of the works for sale at the fair, a trip to the lab is unnecessary—for the most part, connoisseurship still rules the day: “It’s experience, tradition, and a long time spent looking at art,” said Pijbes. “Most of the pieces can be judged on face value.”

But for those that cannot, the Rijksmuseum’s technology can offer invaluable assistance, providing information not visible to the naked eye—expertly repair cracks in an ancient ceramic vase, for instance. (TEFAF requires that such restorations be disclosed by dealers.)

“You want to examine pieces in a nondestructive way,” Pijbes explained. “It’s like in the hospital. If you’re ill, you don’t cut the body open. You have X-Rays to look and see what’s inside.”

He likens art forgeries to doping in the world of sports. But while doping technology is always evolving, leaving top athletes under a constant cloud of suspicion, Pijbes is confident that the art world is up to speed on the latest forgery techniques. “It’s a rat race between the two, but the forgers will lose the battle,” he insisted.

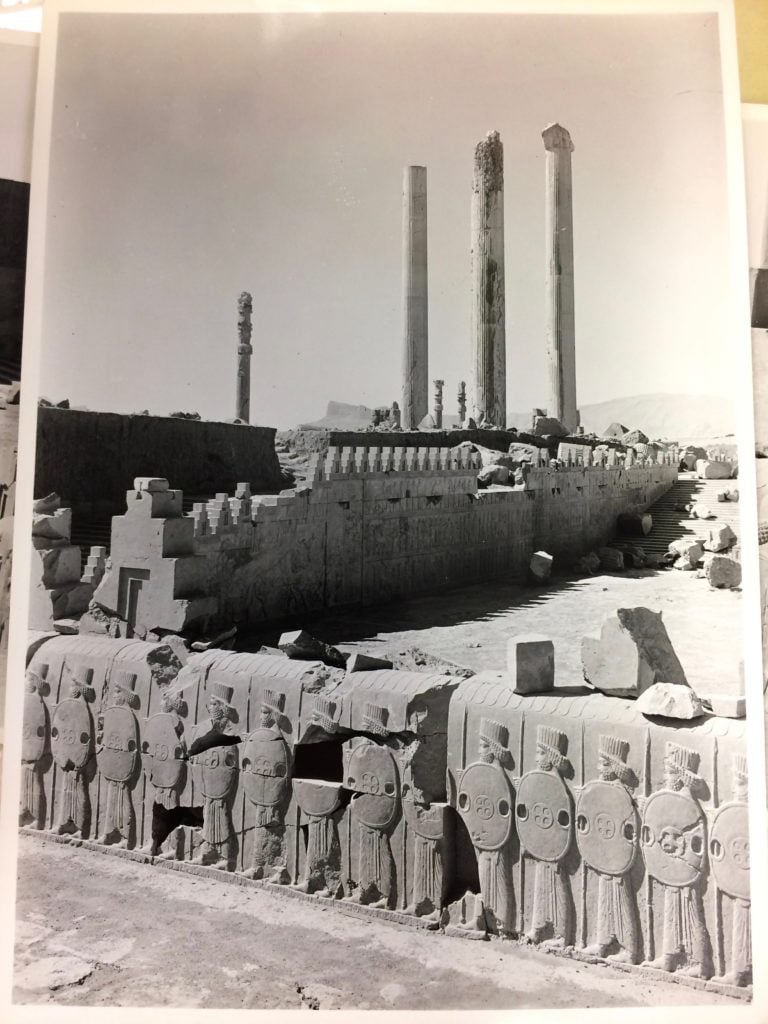

A 1933 photo of the reliefs in situ in Iran. Photo: New York District Attorney.

The peace of mind that comes from vetting is particularly valuable to collectors given all the potential pitfalls involved in high-end art purchases: artworks seized by the Nazis, looted antiquities exported illegally, and cunning modern forgeries dressed up as authentic Old Masters or antique furniture. (In recent years, the latter minefield has ensnared a number of dealers who currently exhibit at TEFAF, although the counterfeit works didn’t change hands at the fair.)

The internet is an important tool for the vetting team, which can quickly search online to verify an object’s provenance. “I call that big data,” Pijbes added. Online research is particularly important in cases of paintings that may have changed hands in Europe in the late 1930s to mid-’40s.

“You have to beware,” said Pijbes. “Red flags could be a pedigree that is not totally sure, especially in the period between 1933 to 1945.”

He is also gun-shy of any works originating from countries in war zones. “Archaeological pieces that have been coming from Iraq the last five or ten years, you don’t want to have that in the show,” Pijbes added. “We don’t go there. That’s too risky.”

The vetting committee will reference the Art Loss Register and always aims to adhere to UNESCO guidelines.

But that doesn’t always address every situation. The field of tribal art, for instance, is becoming trickier to navigate as more African nations are calling for the restitution of objects that have been in Western collections since colonial times.

“Tribal is a moving target, so to say,” said Pijbes, who acknowledges the importance of the current conversations about restitution. But, he insists, “that’s not a black and white situation… it’s not illegal to sell an African statue, it’s legal.”

And despite the vetting committee’s best efforts, sometimes things slip through the cracks. In October 2017, at the first edition of TEFAF New York Fall, the police raided the fair on opening day, seizing a Persian limestone bas-relief for sale by London dealer Rupert Wace. Last July, a judge ruled in favor of the $1.2 million sculpture’s restitution to Iran.

A member of the vetting committee at work at TEFAF Maastricht 2019. Photo by Loraine Bodewes courtesy of TEFAF Maastricht.

TEFAF is by no means the only fair to engage in the practice of vetting. In addition to TEFAF, Masterpiece, and the Winter Show, vetting committees oversee Frieze Masters in London.

But part of the reason that most art fairs don’t go the extra mile to approve each and every object for sale is the expense involved. To make the vetting process happen, TEFAF flies in close to 200 experts and pays for their accommodations in Maastricht.

And there are added expenses for the dealers as well, with the two-day vetting process extending what is already an unusually long fair.

“It takes a lot of time and it costs a lot of money,” said Pijbes. But in the end, it’s worth it: “It’s an extra service to the buying community and to the dealers, to know that they are part of the golden standard of TEFAF.”

TEFAF Maastrict is on view at MECC Maastricht, Forum 100, 6229 GV Maastricht, the Netherlands, March 14–24, 2019.