Artnet News Pro

How Much Art Is Really, Truly Available at an Art Fair? Dealer Thaddaeus Ropac on the Myth, Machinations, and Methods Behind Pre-Selling

We caught up with the Austrian dealer ahead of Art Basel Miami Beach.

We caught up with the Austrian dealer ahead of Art Basel Miami Beach.

Naomi Rea

What’s the point of coming to an art fair if nothing is actually for sale?

It’s a complaint uttered by many aspiring art collectors, who, having finally worked their way onto the exclusive list of VIP preview day invitees, arrive at the fair to find that the goalposts are even further back, as galleries have already offered works to their own select client lists, and have sold everything on the booth before the fair even opened its doors.

Participating in an art fair is not cheap, with associated costs ranging from booth prices to shipping and insurance to travel and expenses. So why wouldn’t galleries minimize the risks by maximizing their chance of sales ahead of the event? The practice of selling in advance also lends galleries the added convenience of being able to send out a rapid-fire press release boasting their impressive first-day sales, and informing the public of just how well the business is doing.

Still, some dealers insist that pre-selling does not happen, that business is just that good, and that sales are only closed at the fair in order to concentrate on developing new relationships. Their insistence may or may not be related to the fact that art fair organizers have historically frowned upon the practice, believing that collectors would be deterred from coming if everything is sold ahead of the fair.

Art Basel Miami Beach is upon us, rounding off a year more jam-packed with art fairs than ever. We caught up with Austrian dealer Thaddaeus Ropac ahead of the fair to tackle some of the myths around pre-sales, get a little art-fair history lesson, and shine some light on the internal operations that make it all work.

Georg Baselitz, Emilio macht das Licht aus (2020). Photo by Jochen Littkemann. © Georg Baselitz. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London, Paris, Salzburg, and Seoul.

Here’s the million-dollar question: Do you pre-sell works before art fairs?

The actual sales happen at the fair. Eighty percent of the works we sell are to people who have visited to see the piece in person. Either the collector or somebody they trust, an advisor or family member. We really entertain this, we give people the extra time. Sometimes if people can’t come on the first day, we’ll keep things on hold for the second day. Of course, it helps if there are other holds as backups, but we are trying to make sure that the works are seen in person.

Pre-sales are real, I have to say, but there’s nothing wrong with this. When people say it’s not fair to the people who have no chance at the fair, I say: we have responsibilities, which are more important than giving everybody equal rights to see something on the opening day. So, yes, we offer works beforehand, but we are doing it in a transparent and, I think, fair way.

Pre-selling has nothing to do with announcing big prices half an hour after the opening. It has to do with our responsibilities. When we get a work—a historic work, or a new work—we have to make sure we are able to place it and we cannot just sit and wait, which we also cannot do in the gallery. Someone cannot walk into a gallery with a checkbook and say, “I’m buying this.” We want to know to whom we are selling. All of this is constantly about being in touch with the right people. Of course, before the fair, we contact collectors we know are looking for the works we are offering.

With a show like Adrian Ghenie [on view in London] for instance, we wanted to know every single person who bought a painting to avoid selling to speculators or to the wrong place. For historical works, we are selling works for our collectors where we are competing with auction houses. Just take Paris+, for example, where we showed an important Baselitz painting from 1970, which, of course, every auction house would want. So we had to convince the collector that we were the right people to place the work. It’s an expensive painting, and we couldn’t just take it on and show it with the risk it might not sell. It would be irresponsible.

So how does it all work?

We are participating in so many art fairs now—we just finished Frieze and Paris+ in October, West Bund in Shanghai, and Art Cologne in November, before we went to Miami—so this has become quite a year-round activity. We have to plan really well, various teams are involved in this. We have to make sure that we aren’t asking our artists for works for fairs too often, and we have to make sure that we show important historical works too. We have to make sure that every fair looks somehow curated, otherwise it becomes just a list of artworks. You can’t just go into your storage and say, “Okay, we’re taking this and that.” We have teams working on each fair months in advance and all of this has become a very complex process.

The way it works is: as soon as we have identified the works we are showing at an art fair, they’re shared with the directors in my gallery. We have six galleries across different cities, and we have 15 directors. So first it’s shared with them. They, in turn, can share it with their relevant clients. So this is the first round, and then we have a meeting where we discuss the different possibilities. And then a newsletter goes out, usually four days before the opening, to everybody who signs up to our mailing list, and this effectively means that anyone can have access in advance. But really, most of the interest comes from those collectors we’ve shared it with personally beforehand.

The industry has changed a lot since you founded your gallery in 1983, and in recent years, quite rapidly. How has the approach to selling at an art fair that you just described to me changed since then?

Everything has changed. The art world has moved from the ivory tower to the center of activity. My gallery will be 40 years old next year, so I have really seen this development. Back then, there was no internet, no Instagram… there wasn’t even email when we did our first art fairs. To share artworks with collectors before fairs, there were these so-called “transparencies,” these very expensive photographs, and you had to have a light table to look at them.

It was a different time. You would send these transparencies to people asking them to send them back because it was so expensive to produce them, and you couldn’t afford to make them for all your artworks, only for the more important works. And you would write to collectors. I remember when we did the first Art Basel fair, we would write letters, which meant each letter was written one by one. You couldn’t copy and paste, you couldn’t use the same content. You had to really write each one and send out photographs.

So we have always prepared for fairs. But it was very different then, much slower. People also didn’t make decisions so quickly. You know, People took their time, they reserved works. They would come back the next day. People used to travel to fairs and stay for four or five days and come back to the fair every day. And the research was incredibly important. Old-school collectors were connoisseurs who would study the work, ask for advice, go to the library, and they would also ask this of the gallery. People still do this, but now access to the information is much easier. Today you just ask, and the internet will give you the answer quickly, and therefore the whole process has been speeding up. We would not be able to do what we do today without it—in the last four weeks, we opened seven major exhibitions and did two art fairs. There is so much and you need these big teams: content teams, research teams, communication teams, all of this is needed to make this happen.

I think I have really seen an extreme change in the past 30 to 40 years, but I think there was no time when it shifted so dramatically as in the past 10 years.

Tom Sachs, Figurative Tower (2021). Photo: Genevieve Hanson. © Tom Sachs. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London, Paris, Salzburg, and Seoul.

And what about the attitude of the art fair organizers? It’s their job to create this retail environment where there’s a sense of urgency, and for people to feel they need to come because the action is happening on the ground. Do the organizers encourage or discourage pre-sales?

It’s the galleries who create the urgency. The art fair organizers are doing their part but they never get involved in sales or in what we’re doing.

It’s a new thing to announce the sales, this is something from the past few years, but it’s also a reaction to a complaint about [market opacity]. The art world always had this rumor about secrecy, that you don’t get to know prices. There was always some suggestion from art fairs that we should write the price on the wall. We don’t do this, because we’re not an auction house and I think this is too banal, too easy. But we do tell people the prices. People were complaining, “Oh you don’t announce the prices,” so when this call for transparency was getting louder, I think we felt: we can say this, we are not hiding what we’re doing. I think it’s just a result of this urge to be more transparent about how much this costs and if it’s sold or not sold, and I think the art world is opening up. Do you have the feeling too, or not really?

Certainly. I mean, I work for Artnet and I think, the Artnet Price Database played a huge role in opening up the art market to this price discovery. And I think that the art market today is the size that it is, in part, because of that price discovery.

Yes, I think so too. And I have got nothing against it. It sometimes looks a bit vulgar I have to say, and sometimes I think, my god, are we really going to push this further? But on the other hand, the market wants this transparency, and auction houses are pushing so much that galleries shouldn’t lag too far behind in the way they are transparent about prices and what sells.

That ties into a question I had about art market reporting. Were journalists always invited to the VIP previews of art fairs, and how has the reporting on the market affected how business is done?

I think journalists didn’t used to be so interested in the market part so much. They wrote about the quality, the highlights, the important pieces. It was a bit more about the art per se and not only the market.

I find that in art criticism, writing about art shows, it is a bit awkward when I read an article about the exhibition we’re showing and the prices are mentioned. Sometimes I would expect a very high-profile newspaper not to go down this path, which is an easy one, to emphasize too much on the prices, but to write purely on the art. Prices can distort any view of a show on an artist. We’ve seen this with Adrian Ghenie, which is also almost an extreme example of course, but sometimes I wish art criticism on a certain level would not mention the prices.

I hear that. I think as a journalist—not a critic—I feel that would be maybe somehow dishonest. You can look at art just for art’s sake, but should you look at an artist in the context of a commercial show, and divorce it from the market?

No, I understand this and I totally accept this and respect it. And we still have enough media that doesn’t do this. Artforum and other great art publications would never write about the prices. But I’m surprised sometimes by some of these really important daily newspapers that have focused more and more and more on the market, and describe works with the price. I’m saying this because you’re asking about change and this didn’t happen before. It was unthinkable before.

So you do this advanced sales work ahead of art fairs, but you’ve said you often actually wait until the day of the fair to close. Is that a hard and fast rule?

Not necessarily. If somebody is absolutely sure they want to go for something, but this is a very small percentage. As I said, 80 percent of the time sales close at the fair because people want to see the work physically. And by the time we’re sending out the information to our collectors, the work is already in transit so they cannot say: okay, I’ll fly to Paris or to London to see it in the gallery because it has already gone. So you always have these four weeks where you can’t show it because it’s in transit.

How does this play into the logic around the rehang?

Usually, we would not change an installation on the first day once works have sold. We would not change the presentation of the booth. Sometimes it’s tempting because we could show something else, which we haven’t sold, and we do change usually after one or two days so we always have an entire second shipment, but we still show works when they have sold the first day.

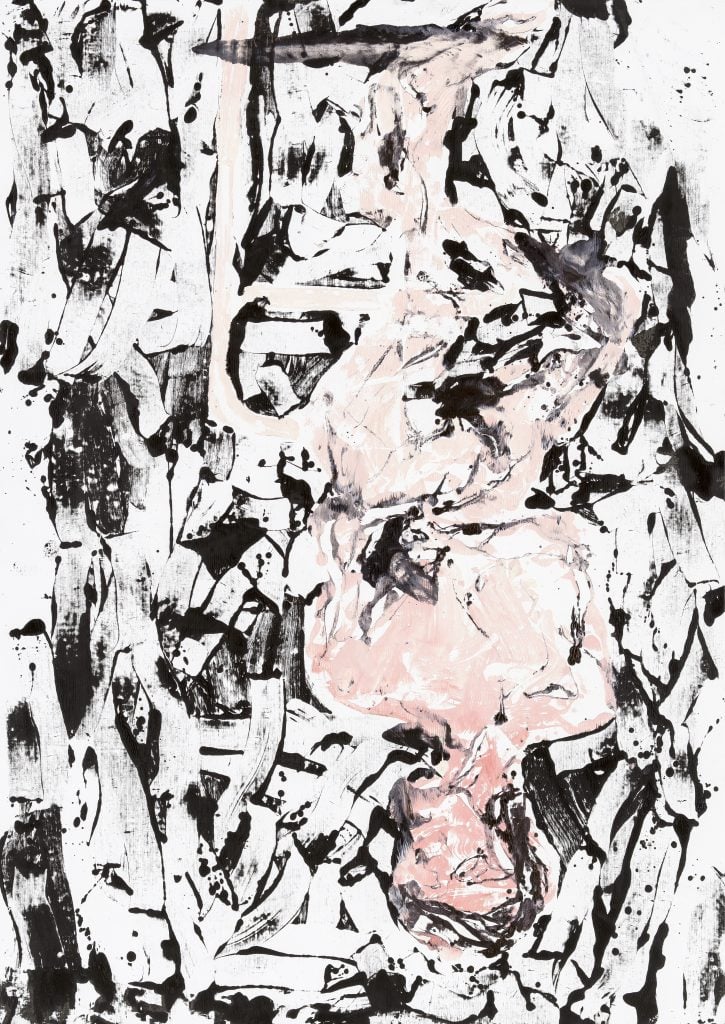

Megan Rooney, Late Air (sun) (2022). Photo: Eva Herzog. © Megan Rooney. Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac gallery, London, Paris, Salzburg, and Seoul.

So what percentage would you say of the works that are on the booth, say at Art Basel, would be reserved or sold on the first day?

A lot. On the wall, I think almost everything, which is exhibited on the first day is either sold or reserved. Almost everything. But the same thing at Frieze and Paris+. In Paris, every piece had strong reserves, sometimes two or three, because there is always a backup. Everything.

We’ve talked a lot about the big fairs. How does your strategy change when we’re talking about the regional art fairs?

At regional art fairs, we like to use the format to focus on one artist or three artists or a young artist. For example, at ARCO Madrid, in the last two years, we did Martha Jungwirth and Antony Gormley. At the big art fairs, we want to really show our program a bit. We always try to curate according to the place where the fair happens so it has its own DNA.

For instance, at Paris+, we were showing historical works, because Paris is always a place for great masterpieces. Frieze always means new works, not necessarily by young artists, but new works from the studio. So we are using every fair, very precisely. One thing cannot look like the other.

You mentioned earlier this idea of competition coming from the auction houses. Pre-sale guarantees are quite common now with auctions. Has a collector ever “guaranteed” an artwork at a fair, or have you ever considered offering that arrangement of pre-selling lower and offering at the fair for a higher price?

No, because it’s different in the primary market. We are only interested in the final destination for the work. We are not interested in somebody guaranteeing a work and then selling it on. This is not our interest. We’re trying to avoid this at any price. Any price. So therefore it’s a hundred percent different. We’re not interested in any underwriting or financing. People come and ask for it, and want it, but we are not interested. We’re trying everything to avoid this.

As a collector, are you more likely to get a good deal/discount if you buy before the fair or during (or after)?

Why would they get a discount at the fair? No. These are the prices. Sometimes people think that the prices are either higher or lower. You know, I’ve heard people say, “Oh, I prefer to buy at art fairs because the price is lower.” Why would you think this? Or “Oh, I prefer to buy at the gallery,” for the same reason. We are very transparent about prices in that we say: “This is the price.” For certain new paintings, by Baselitz for example, the price is the same at the gallery and at an art fair. Any discussions about discounts are individual and there’s no general way of dealing with them, but prices are the same, and they’re even the same between galleries. If there are three galleries that represent an artist, the price is the same. We make sure of this. But not with historical works, because when you sell something historical then you have to take many other things into consideration. I think the art market in the primary world is so much more transparent than people think. People have such imagination but it’s very clear.

What, if anything, would you like to see kind of change about the way that business happens at art fairs—whether from your side, or the organizers, or from the clients?

Well, first of all, I’m a big advocate of gallery exhibitions. I always feel you should draw audiences back to the gallery because this is the more serious way of looking at art and learning about artists.

Sometimes I wish we had a bit more time, but it’s also something which is irrelevant to wish for because I complained maybe five years ago about this speed, and it did not get better, but only even more intense and, even faster, I think. I wonder where the speed will stop and I wish we could just stop this rush. But maybe the rush is needed because that is how the world is functioning, and the art world cannot stand out and be in a bubble working at a different speed. There are many things I wish we could change, but I’m realistic enough to know that it’s not possible.