Galleries

Thaddaeus Ropac on His Lavish New London Gallery—and Why He Isn’t Afraid of Brexit

On the eve of the opening of his newest outpost, the Austrian dealer tells us what drove him to expand to the UK.

On the eve of the opening of his newest outpost, the Austrian dealer tells us what drove him to expand to the UK.

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

Last June, exactly a week after the shocking Brexit vote, powerhouse Austrian gallerist Thaddaeus Ropac announced plans to launch his first outpost in London. The timing was curious. As many were voicing concerns about the future of the London art market, Ropac was placing a big bet on its survival.

Ten months later, the British government has begun to negotiate its withdrawal from the European Union—and the gallery opens to the public tomorrow. It is, indeed, one of the most anticipated events on the London art calendar this spring.

Located in the 18th-century mansion of Bishop Edmond Keene of Ely in Mayfair, the gallery spans 16,000 square feet across five floors. It is the size of a small museum.

Façade of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac London, Ely House, 37 Dover Street. Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

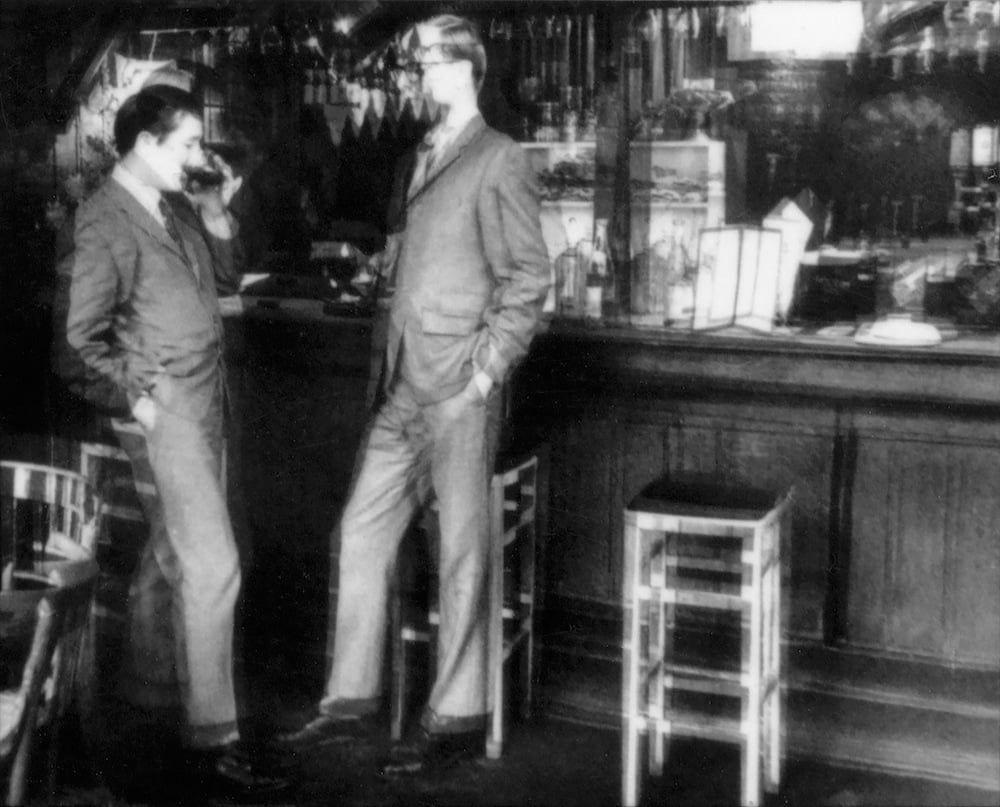

The ambitious inaugural program comprises four exhibitions: Gilbert & George’s “Drinking Pieces & Video Sculpture,” featuring a group of works from 1972-73; a selection of paintings and sculpture from the Marzona Collection of Minimalism and conceptual art, which was recently acquired by the gallery; an exhibition of early drawings and a major sculpture by Joseph Beuys; and a presentation of works by the young British artist Oliver Beer, including a live performance and a site-specific sound piece.

Gilbert & George, Smashed (detail)(1972). Photo ©Gilbert & George,

courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

Ropac’s growing empire began in 1983, when he opened his first space in Salzburg at the tender age of 23. He expanded to Paris in 1990, launched a second gallery in Salzburg in 2010, and a massive complex in Pantin, the developing northeastern area of Paris, in 2012.

Earlier this week, as he put finishing touches on the new space, artnet News met with Ropac to discuss his motivation to set up shop in London, the future of the middle market, and why he isn’t afraid of Brexit.

Why open a gallery in London, and why now?

After successfully operating two galleries in Salzburg and two large spaces in Paris, we felt London would add to the gallery’s portfolio and that our artists would benefit from it. We started thinking about London after the Pantin space was launched in 2012, but it took us two years to find the right place—a historic building in the heart of Mayfair.

London is one of the quintessential art centers and there’s a critical mass of cultural activity there that you won’t find anywhere else. The city attracts great artists and is home to some of the best museums in the world, and it has a creative energy that keeps on inspiring.

The ambition that I have for my gallery is to create an expertise to support my artists in Europe, where we know every collector and every curator from Scandinavia to Naples. I always say that it isn’t good for an artist to be represented by the same gallery worldwide—for artists, it’s always better to be represented by two or three galleries…in America, in Asia, and in Europe. I kind of like being in competition with my colleagues, so London was the natural next step.

Galerie Thaddeus Ropac London, Ely House staircase, 37 Dover Street. Photo Hugo Glendinning, courtesy of Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

It’s a complex time to open a gallery in London. Your official announcement came shortly after the Brexit vote, and the opening comes shortly after the actual start of the Brexit negotiations. Are you worried about the impact that the political situation will have on London’s position as an art market and financial hub?

Personally, I strongly believe in the vision of Europe, so it was hard for me to see Britain choose to leave the European Union. But professionally, I believe the art world has long expanded beyond any geopolitical borders and that it operates by its own rules. So I don’t think London will suffer as a key art hub, even if administration will become more complicated, and we will have to go back to procedures we all thought we had left behind. Maybe in five years, I will realize that I was wrong, but right now, this is what I truly believe.

The gallery is in an unbeatable and historic piece of real estate, Ely House, and boasts four distinct spaces. It is a big and bold statement. What do you hope to achieve with it?

As a historic landmark, Ely House offers challenging spaces for a range of distinct exhibitions. In this sense, the four inaugural exhibitions are our mission statement: new performance and sculptures by young British artist Oliver Beer, who’s had a lot of attention internationally; early works from the 1970s by Gilbert & George, whose work is part of my DNA as gallerist; American Minimalist art from the Marzona collection, which is a movement I haven’t really worked with but that I have collected personally; and an iconic sculpture by Joseph Beuys with early drawings, which precede an important Beuys exhibition which will take place next year.

Donald Judd, Untitled (1989) (right) and Carl Andre, Tenth Copper Cardinal (1973). Photo Steve White, courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

The refurbishment has been completed by Annabelle Selldorf, who is becoming extremely sought-after in the art world. What drew you to her?

Ely House is a Grade I-listed building and to refurbish its historic interiors was a huge task. We had to consult Westminster Council and English Heritage for every little minor change. Annabelle Selldorf understands the DNA of historic buildings and knows how to adapt them for 21st-century use. What she has achieved with the Neue Galerie in New York and what she is planning for the Frick Collection made her the best architect for this project.

The four inaugural exhibitions cover a wide range of styles and media, but are not very diverse in terms of gender. Is expanding your roster of artists to feature more female practitioners something that concerns you?

We are very happy to show a major work by Lee Lozano, which is a highlight of the exhibition Minimalist art from the Marzona Collection. We are looking forward to a project in London with the estate of Sturtevant, an artist we have worked with for a long time. And Korean artist Lee Bul recently visited the space in London for a future project.

Joseph Beuys, Backrest of a fine-limbed person (hare-type) of the 20th Century AD (1972-1982)©Joseph Beuys Estate/ DACS, London 2017. Photo Ulrich Ghezzi, courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

In recent years, the gallery has been expanding at a somewhat relentless pace. Besides dealing in both the primary and secondary markets, your gallery also acts as a consultant to public institutions, as an advisor to private and corporate collections, and operates its own publishing house. It seems that a few top international galleries are consolidating power and reach—acting almost like museums that also work in the commercial sector. At the same time, a growing group of mid-tier and younger galleries are being forced to downgrade or close their spaces. What do you think about this market dynamic?

We don’t see growth as a necessity, but as an opportunity. To be a great gallery, to serve your artists, you don’t need to constantly grow. It’s just an opportunity, which you take if you can. Of course, we will do anything to serve the vision of our artists, and bigger spaces are one of the means to reach this goal. I really believe in the important role of mid-tier and younger galleries and I only want to encourage them to continue their indispensable work, as I emphasized recently in a keynote speech at [the art market conference] “Talking Galleries” in Barcelona.

Many blame the recent gallery closures on the growing power of art fairs, which can strain galleries’ resources and budgets. Do you think there are too many art fairs at the moment?

We successfully participate in many art fairs, but I always say that 75 percent of our activity and business has to be in the gallery. I think art fairs are very important, but they’re important to connect: to connect people, to exchange information, and to sell art, of course. But they can’t replace the exhibitions at our gallery spaces.

We put every effort into [our gallery shows]: we think about every detail, about the floor, the wall space, the height, the lighting. Everything has to be perfect, and we want to invite our collectors and audience to experience art in the best conditions, while at an art fair we need to accept imperfections. I’m convinced that we have to keep the soul and the core of our business in our gallery spaces.

Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac London opens to the public tomorrow, April 28, at Ely House, 37 Dover Street, London.