Galleries

Grow or Go: Do Art Fairs Need to Expand to Survive?

Competition is increasing as fairs muscle in on each other's turf.

Competition is increasing as fairs muscle in on each other's turf.

Brian Boucher

TEFAF, the prestigious annual fair that has called Maastricht, the Netherlands, home for four decades, is now breaking into the crowded New York art fair landscape with not one but two fairs. One, premiering in October 2016, will show art from antiquity to the twentieth century. Another, launching in May 2017, will emphasize modern and contemporary art and design. The New York expansion is, as per the fair’s organizers, the result of years of research and may increase the already cutthroat competition on the New York fair scene.

Though TEFAF is among the most senior art fairs, its expansion didn’t come as a huge surprise. Fair expansion to other cities and continents has become regular news these days. But has it become a necessity? Do fairs need to grow in order to simply survive?

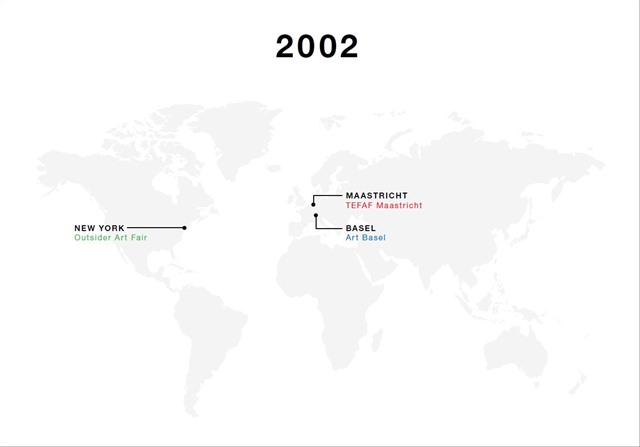

Art Basel was content to remain in Switzerland, where it started in 1970, for more than thirty years, but it expanded to Miami Beach in 2002—the most visible member of the Basel fair family—and Hong Kong in 2013, when it purchased the existing Art HK. Frieze Art Fair launched in London in 2003; after a decade, it expanded twofold, launching Frieze Masters, for historical work, and Frieze New York, for contemporary art, in 2012. In just a few years, Frieze New York’s attendance has grown to some 40,000 visitors.

These three art fairs each had just one location in 2002.

Image: Robert McConnell for artnet News.

It’s not only the biggest that are growing. Even boutique fairs have set their sights in other cities and regions.

NADA Miami Beach, the main attraction in that city after Art Basel, launched in 2003. In May 2012, it initiated NADA New York during Frieze New York, and in 2014, it launched Collaborations, a project with Art Cologne. The Independent art fair first opened in New York in March 2010 (during the Armory Show, then New York’s only major art fair), and announced a year ago that it would set up shop in Brussels in April 2016, timed to Art Brussels.

Then there’s the Outsider Art Fair, inaugurated in New York in 1993. The scrappy fair was snapped up in 2012 by longtime New York dealer Andrew Edlin, who quickly announced that he would bring the show to Paris, where it landed in October 2013, to coincide with FIAC (Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain). In fall 2015, it held its third edition, which had fifty percent more exhibitors than the first two.

Expansions don’t always pan out. Paris Photo, launched in France in 1997, expanded to Los Angeles in 2013, but just this month, only two months before its fourth edition was scheduled, the organizers pulled the plug on the California event. A FIAC Los Angeles was to be organized by the Reed Expositions, which also puts on the highly respected French Foire Internationale d’Art Contemporain, but now that won’t happen at all. (Last year, it announced a postponement of a planned 2015 outing.) Reed also this week canceled Officielle, FIAC’s own satellite fair, which was to take place in October.

Inside Frieze New York.

Photo: Courtesy of Marco Scozzaro/Frieze

Defensive Moves, Offensive Gambits

In branching out to other countries, art fairs are actually mimicking a longstanding move by galleries that is often characterized as, at least in part, playing defense.

Gagosian has a baker’s dozen locations, from New York to Hong Kong. Sprueth Magers just opened their LA outpost and Hauser & Wirth, with three international locations to its name, will soon add a fourth in the same city. Pace Gallery’s locations stretch from New York to Beijing, and David Zwirner is looking to open a gallery in Hong Kong. Increasingly, it seems that galleries have to grow to succeed, if only so that they can offer their artists representation in more than one market, thus protecting themselves from having their artists poached by galleries with a larger footprint.

Similarly, TEFAF’s expansion, according to several insiders, seems to serve partly as a bulwark against a possible Frieze Masters New York.

But they’re not just defensive moves.

“When Frieze came to New York, they wanted to kill the Armory Show,” New York dealer Sean Kelly told artnet News. “I then joined the selection committee at the Armory Show because I thought that was quite bad form.”

Similarly, TEFAF’s October fair, focusing on antiquity to 20th-century art, may be not only defensive but also a “head-butt,” as one fair organizer called it, talking to artnet News confidentially; it will take place during same month as Frieze Masters, which surveys the same material.

“We never think of competing with anyone else,” TEFAF board member Michel Cox Witmer told artnet News when asked if the planned October fair in New York was meant to compete with Frieze Masters (though that fair is in London), “but instead we concentrate our efforts to make TEFAF the best that it can be.”

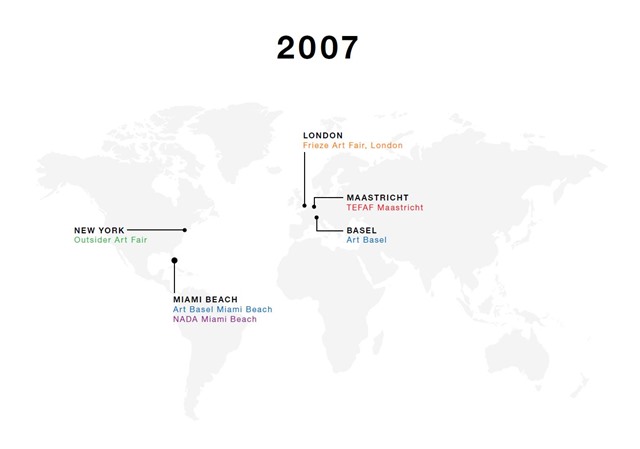

By 2007, Frieze had sprung up, and Basel had expanded to Miami Beach, where it was quickly joined by NADA.

Image: Robert McConnell for artnet News.

Location, Location, Location

“The US remains the largest, richest, and most stable force of today’s art market,” said Cox Witmer about why TEFAF settled on New York as the site of its new outpost. (New York is also easier to travel to than Maastricht, which is tricky to get to unless you have a private jet.) He also noted that the fair had considered expansion in other markets such as South America, Asia, or other parts of Europe before settling on New York. TEFAF had announced in 2013 that it would stage an event in Beijing, but that plan was scotched nine months later.

That aborted expansion highlights what is perhaps the all-important factor: location, location, location. For example, Basel’s expansion to Hong Kong rather than China was shrewd because tax regulations make the mainland a difficult place to do business. Its growth to Miami gave it a foothold in the Americas in a city that wasn’t already stocked up with competitors—it’s also a major tourist destination.

Location is vital not only in terms of what city you expand to, but what specific address you occupy. TEFAF’s twofold New York outpost could prove to be trouble not only for Frieze Masters, but also for Frieze New York. Since its spring fair in Manhattan will include contemporary art, it could potentially present competition for dealers at Frieze New York, which happens simultaneously.

In this regard, Frieze New York’s inconvenient location, on Randalls Island in the East River, could work to its disadvantage.

“It’s incontrovertibly true that Frieze New York is a one-day fair,” Sean Kelly said. Traffic to and from the fair gets badly backed up since Randalls Island is not built to support that many cars, and the only other alternative is a ferry ride, also not convenient. So buyers attend during the opening day but don’t make return trips.

“At Armory, by contrast, we do the same amount of business on day three and day five as we do on day one, and I make vastly more sales there overall,” Kelly added. “Now, that said, Frieze does a very fine job, and we do enough business on day one that we’re always very happy to be there.”

A representative of Frieze rebutted Kelly’s observation, pointing to a press release where Akio Aoki of Vermelho Gallery (São Paulo) said that she had seen “consistent sales throughout.” But director Victoria Siddall conceded in an email to artnet News that “visitors will also want to spend time around the city” seeing museums and galleries. “We encourage this,” she said.

The Frieze representative also pointed out that as of this spring there will be a new ferry line, leaving from East 90th Street and taking five minutes to get to the island.

But if limited sales due to the out-of-the-way location caused so-called “anchor” exhibitors like White Cube and David Zwirner to decamp to TEFAF at the more central Park Avenue Armory, said one art advisor, it could lead to an exodus. (In fact, Frieze’s advertising has recently featured more prominent images of the Manhattan skyline, as if to de-emphasize its site.)

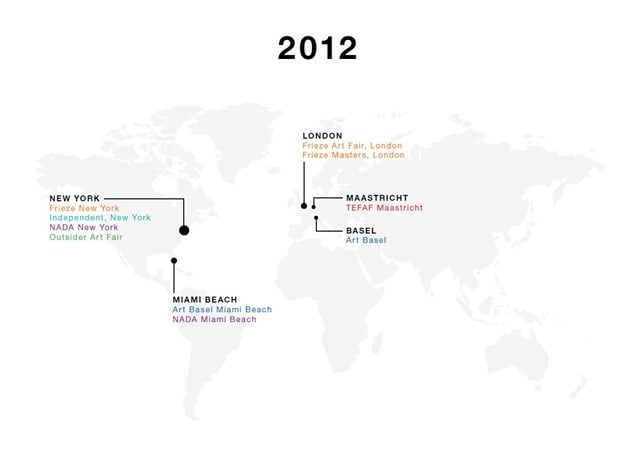

By 2012, Frieze had tripled its offerings, NADA had come to New York, and Independent had launched.

Image: Robert McConnell for artnet News.

And though TEFAF’s spring fair doesn’t occupy the same time slot as Armory, some insiders wonder whether TEFAF could pose serious competition to that fair as well, especially since the Armory’s Pier 92 includes modern art. Armory, one dealer said, doesn’t have the prestige of Frieze or the Basel fairs, and lacks the “snob appeal” of FIAC.

Could TEFAF, known worldwide as a top-notch affair, poach some dealers from the dowdy piers?

“The Armory has such a strong hold on a certain kind of American contemporary collector,” said New York art adviser Heather Flow, “that I’m not sure that TEFAF could really break into that market.”

The two TEFAF fairs will be taking the place of two existing events in the New York fair calendar: the fall fair will replace the International Fine Art & Antiques Show and the spring fair will replace Spring Masters, both of which are organized by Artvest Partners.

“The Park Avenue Armory is smaller, so it can’t accommodate as many dealers,” said Armory director Ben Genocchio. “The booth sizes tend to be smaller, so I think you will find that the two fairs will remain quite different.”

“The issue in coming to New York,” said Michael Plummer, one of the principals of Artvest Partners, over email, “was the limited exhibition space that is of the quality of the Park Ave Armory.” He noted that TEFAF Maastricht is used to a much bigger footprint at the Maastricht Convention Center with 200 plus dealers accommodating over 70,000 visitors. “TEFAF is not coming to New York to wipe all the others off the map but rather to fit into the existing fair landscape.”

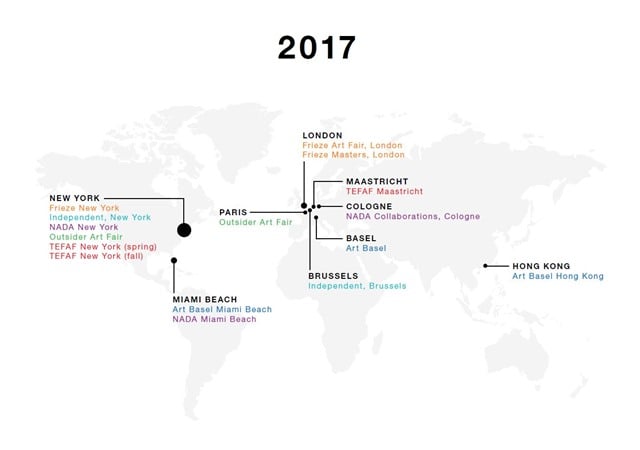

By 2017, TEFAF will have two New York fairs. Others have expanded further.

Image: Robert McConnell for artnet News.

All Fairs Are Local

The fair expansion phenomenon could be said to reflect a growing regionalization of the art market with fair operators serving clients where they live.

“Ten years ago it was a must to travel to Basel, whether you lived in Bangkok or in Bogotá,” Belgian collector Alain Servais told artnet News in an email. “Today, because of the presence of strong fairs on the three main continents, one can go to Art Basel in Hong Kong if traveling from Bangkok or Art Basel in Miami Beach or Frieze New York if coming from Bogotá.”

But that’s not without its downside. “It’s good for CO2 consumption,” adds Servais, “though less so for diversity and cultural exchange.”

Sadie Coles Gallery at Art Basel in Miami Beach 2015.

Photo: Art Basel.

But growth of this kind isn’t for every fair, and some directors say it would only dilute their focus.

“I have no plans for expansion,” Expo Chicago director Tony Karman told artnet News in a phone interview. “That means I put my effort and that of my staff on one fair. It allows us to focus and make this show of the highest level in order to best support the exhibitors.”

Genocchio was even more pointed. “We are not a franchise fair, making us basically unlike everyone else,” he said. “We are and aim to remain the American art fair, not a carpetbagger operation that blows into town once a year for five days.”

“We’re not an art fair corporation looking to increase our global influence,” said Elizabeth Dee, co-founder of Independent. “We’re not operating on that model or with that ambition. We just want to serve the people who are most important: the artists and the galleries that serve them.”

During an interview at Spring Street Studios, the new Tribeca venue for the Independent, which used to take place in Chelsea, Dee noted that expansion has its costs. “We had to triple our staff to expand to Belgium,” she said, acknowledging with a laugh that that meant growing the number of employees from three to nine.

While initially aiming to serve mostly European dealers showing artists who are not in the public eye in New York, Independent has now successfully found its footing, according to Dee, and the fair’s expansion to Belgium allows them an additional platform closer to home.

Whatever the rationale behind expansion, if it means more fairs to attend without requiring visitors to set foot on a plane, local collectors are the ones who win out.

Additional reporting by Eileen Kinsella.