The sand-filled, dusty streets of Alserkal Avenue, Dubai’s leading art district, were deserted. At the back entrance to the industrial compound, guards wearing face masks took the temperatures of the few visitors who were trickling in. But because of the Gulf’s hot weather, which had hit around 104 degrees Fahrenheit (40 Celsius), several visitors had to spend a few minutes in a cool waiting area and then have their temperature taken again for an accurate reading before being allowed entry. Once inside, artwork spray-painted on the street with messages such as “It’s not you, it’s COVID-19” and “A Two-Metre Distance Makes the Heart Grow Fonder,” reminded all of what they had just been through: weeks of stringent 24-hour lockdown.

The signs of life at Alserkal marked a new beginning. Galleries were finally re-opening their doors (if only by appointment). But some wonder whether this slow revival of activity will be enough to support a cultural sector that was ailing even before the onset of coronavirus.

High Hopes

The year 2020 was one Dubai’s leaders had long awaited. After two years of economic recession and slow growth, a spirit of optimism was in the air as the UAE prepared to host Expo 2020, a world fair that was expected to draw around 25 million visitors and renew Dubai’s glittering image on the world’s stage. But those plans were derailed when Dubai recorded its first cases of coronavirus on January 29.

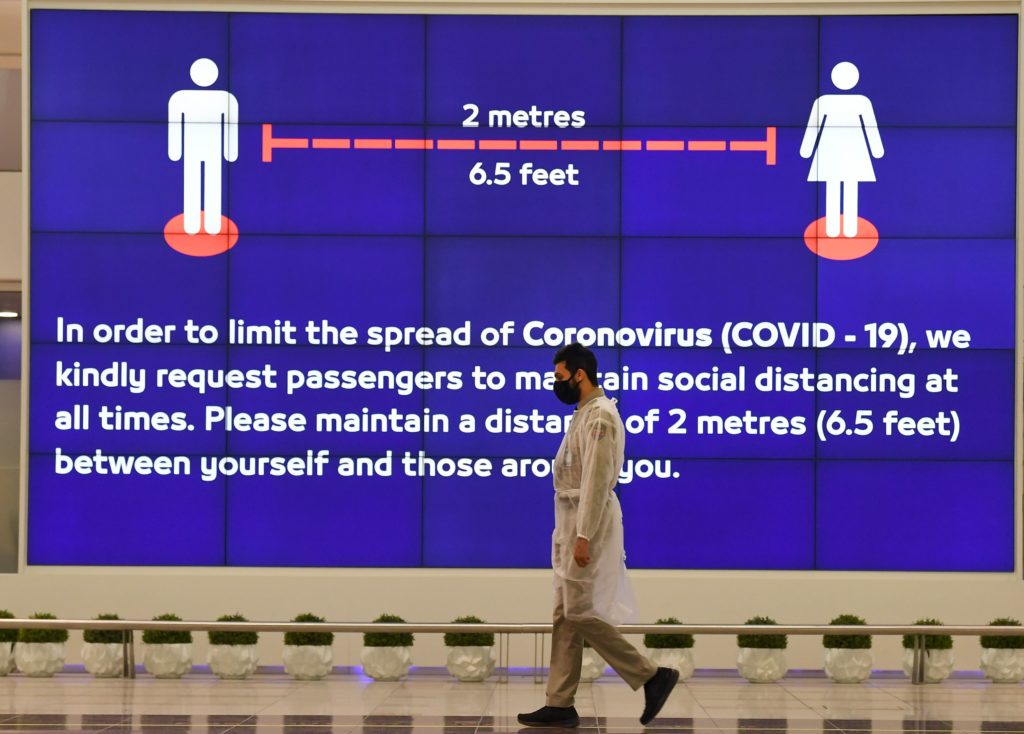

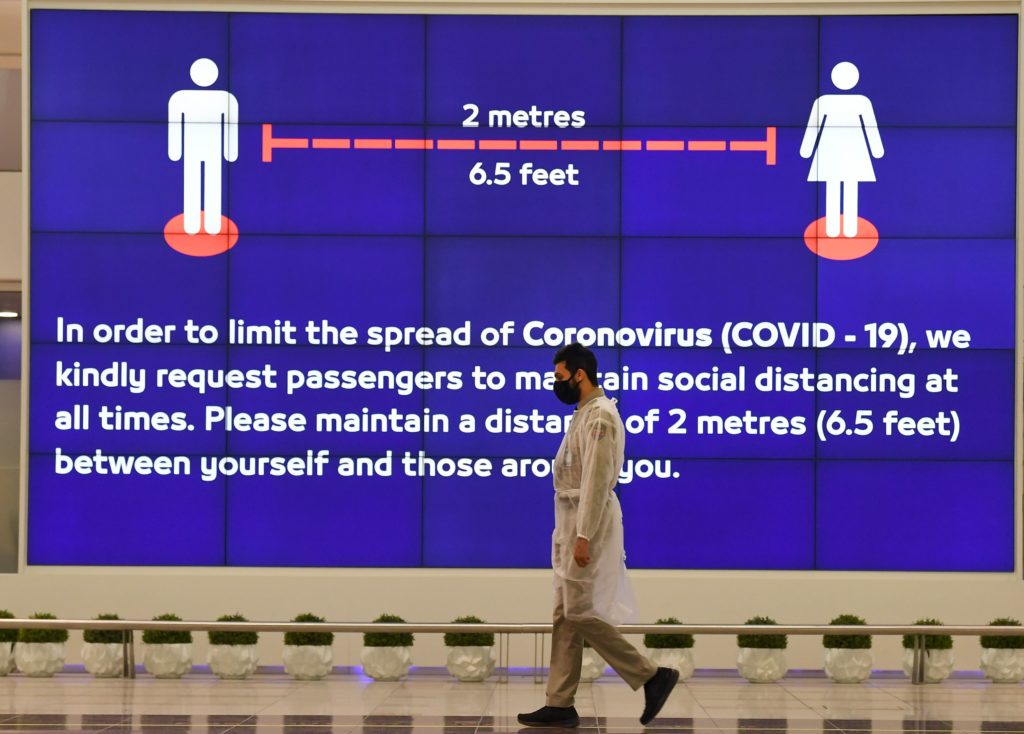

An employee at Dubai International Airport. (Photo by KARIM SAHIB/AFP via Getty Images)

Dubai’s open economy, which relies on trade, tourism, transportation, and retail, was hit hard not only by the emirate’s 24-hour curfew at the height of the crisis in April, but by the spectacular collapse of crude oil prices caused by a price war and a lack of demand. Oil is now $30 a barrel, down from an average of $65 last year. As a result, finance ministers across the oil-rich Gulf have dramatically cut spending.

The much-anticipated Expo 2020 has been postponed to fall 2021—and the UAE, even as it rushes to reopen businesses, is bracing itself for a tough few months, if not years, ahead.

The very strengths that have allowed Dubai to shine have now exposed its weaknesses. Hospitality and tourism—two vital sectors to the emirate’s economy—are also crucial to the wellbeing of the UAE’s art market. In the midst of closed borders and a lack of foreign visitors to the UAE, these sectors have taken a severe hit.

Courtesy of Seeing Things Photography & Film.

An Economic Quake

Even before the onset of coronavirus, as property values slumped 30 percent from a 2014, “we all knew that we were going into a recession,” said Charles Pocock, managing partner and director of Meem Gallery.

But coronavirus has thrown fuel on the fire. In late April, during the city’s most stringent lockdown period, the Dubai Chamber of Commerce surveyed 1,228 CEOs across a range of sectors; they concluded that around 70 percent of Dubai companies were expected to go out of business within six months.

For galleries, the urgency is similar. “I am not very hopeful; I don’t know what the galleries will do,” said a gallerist who wished to remain anonymous. “By November, there will be a very different art scene here.”

Over the past two years, some gallerists and other art professionals were already whispering about their desire to move elsewhere—or, at the very least, to find a way to split their operations between Dubai and another location in order to attract more international buyers. That desire has accelerated now, although it has also become logistically more difficult.

“It has never been a purely local art market,” said Asmaa Al Shabibi, co-founder of Lawrie Shabibi. “It’s really a global market that Dubai caters to. We were always going to have a foot in Dubai and a foot in London, so the crisis has definitely sped this up.”

Both Lawrie Shabibi and The Third Line—another gallery in Alserkal Avenue—planned to open UK outposts in Cromwell Place, a new co-working art complex in London, this fall; the facility’s opening has since been delayed.

“Even before COVID-19, I had started to realize that most of our collectors are not here,” said Sunny Rahbar, co-founder of The Third Line. “Doing shows just in Dubai wasn’t making enough money.”

Most of what is selling now, dealers say, is editions, works priced at less than $10,000, or more expensive works by established artists. But many local galleries lost their biggest money-making opportunities of the year with the cancellation of Art Basel Hong Kong and Art Dubai. During the shutdown, Shabibi estimated that the gallery made around 30 percent of the sales it would make during a normal year. “The middle market here… is flat,” said Pocock.

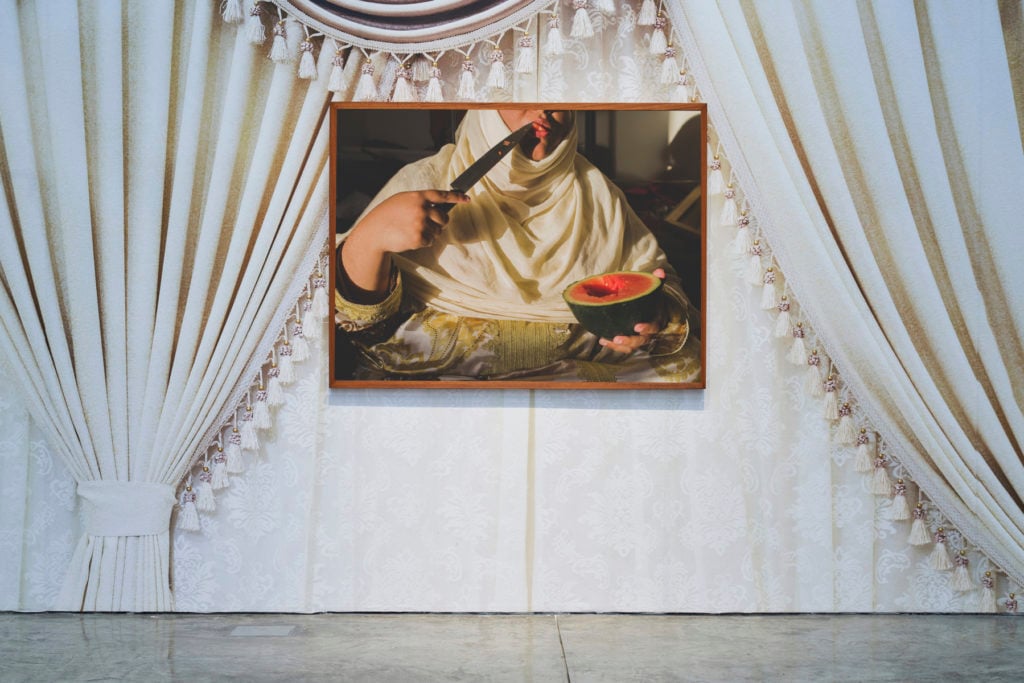

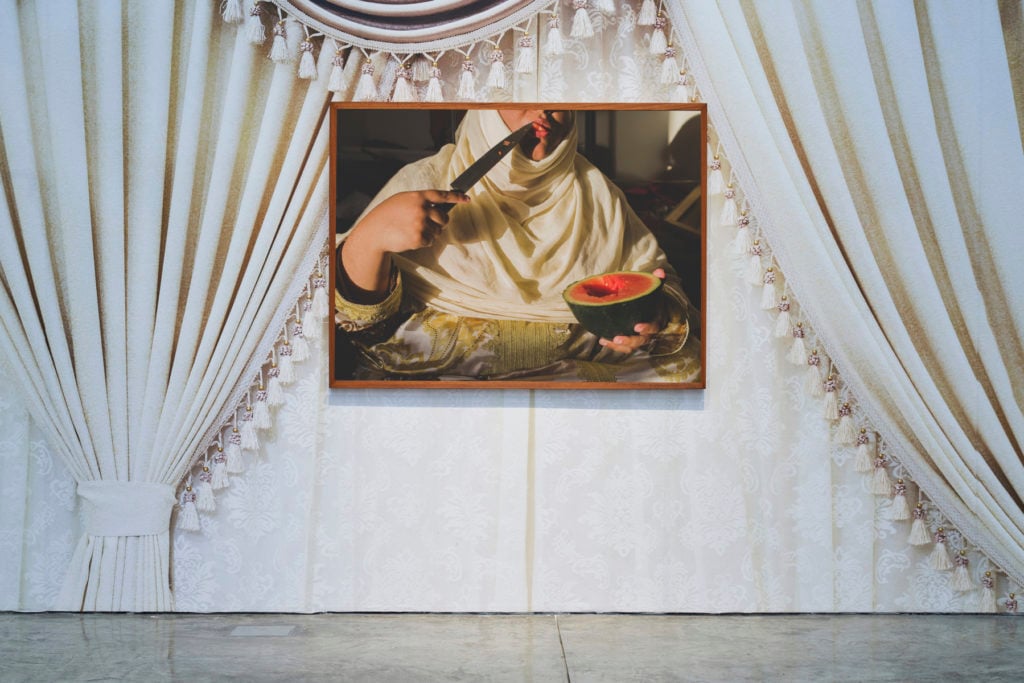

Farah Al Qasimi, Arrival (2019) installation view. Courtesy of the artist and The Third Line, Dubai.

Surviving, which for many galleries is month to month, is only going to get harder and harder. “The crisis also hit just before Ramadan and summertime which is already a dead time here,” said Rahbar. “What we have to recuperate now is huge.”

A Renewed Local Art Scene?

To address the shortfall, the government is pushing locals to invest in culture. “I believe the creative sector of our economy is of vital importance,” said His Excellency Zaki Nusseibeh, the UAE’s Minister of State, during a Zoom discussion last month on Sheikh Zayed’s cultural legacy. “I believe there is a duty on all of us, patrons of arts, critics of art and lovers of art to go out and actually buy art now.

Some longtime collectors are embracing the moment. “I haven’t stopped collecting but the focus of my collecting has changed,” said UAE-based lawyer and collector Nassib Abou-Khalil. “It’s of utmost importance to me now to support local artists and galleries.”

If this spirit became more widespread, it would mark a considerable shift for the scene. “The local UAE art market has never been supported by the local collector base,” Mohamed Somji, founder of Gulf Photo Plus, a photography center in Dubai. “This moment of crisis can be seen as an opportunity to… get a new crowd in.”

But in the UAE, the distinction between local and international isn’t always so clear. The emirate has long lured young entrepreneurs to its sandy beaches and glittering skylines with the promise of a good life and new business opportunities—so long as the cash keeps coming. As job loses mount and new opportunities are hard to come by, many expats are packing their bags and going back home.

“Some people speculate that Dubai may go backwards to the small city it was in 2004 and 2005,” said one gallerist. “If the supposed exodus comes then that will be a big wake up call for the government.”

The current impasse also reveals just how much the UAE has built up its cultural capital by bringing in outside artists, curators, and speakers, said Hanan Sayed Worrell, an Abu Dhabi-based cultural advisor. Even as the emirate has become “a refuge for many artists and creatives from the region… it’s a scene that has depended on an international audience.”

Courtesy of Seeing Things Photography & Film.

Are Private and Public Subsidies Enough?

Can a local market—even a reinvigorated one—alone keep the art scene afloat? As job losses, furloughs, and redundancies mount, Dubai’s private sector has proposed a series of government interventions, which include state-subsidized loans as well as help covering salaries, rent, and lower taxes. The Ministry of Culture and Knowledge Development also launched the National Creative Relief Program to offer grants to creative freelancers in the range of Dhs15,000–50,000 ($4,000–13,600).

“Creative and cultural sectors aid in diversifying the UAE economy,” said Noura Al Kaabi, Minister of Culture and Knowledge Development for the UAE, during a recent online gathering of leaders from the Middle Eastern art scene. “If there are freelancers or businesses struggling, let us know.”

But some say the government should be doing even more to help the cultural sector directly. “Look at what the governments of France and Germany did for their cultural sectors. Why hasn’t that happened here?” said the anonymous gallerist.

Meanwhile, a host of other private and public-private initiatives have popped up to help the creative industry survive. These include Alserkal Avenue’s Pay It Forward Program, which invites the Alserkal Avenue community members to apply for a subsidy to support their lease commitment for one quarter in return for a commitment to give back and support other businesses in the community.

On May 10, Warehouse421 launched its Project Revival Fund, open to all creatives from the MENASA region and offering monetary packages up to $2,000. Art Jameel also redirected its budget to offer is micro-grants to regional artists and curators of up to $3,000—and has already received more than 400 applications from 17 countries.

Jameel Arts Centre Dubai (rendering). Courtesy of Serie.

Collaboration, everyone agrees, is key to survival at a moment when cash is quickly disappearing. “We cannot just wait for the government to step in,” said Pocock. Amidst invigorated digital platforms for art sales, UAE gallerists have also spoken of shared spaces and teaming up to host exhibitions.

“I don’t know if we will all be able to sustain and go forward if we can’t work together,” Rahbar said. “Whatever you are going to buy this year, buy it locally. We aren’t trying to compete at this point, we are just trying to survive.”