Analysis

A New Study Suggests Why Museum Architecture Is So Curvy—and It’s Not Because Visitors Like It That Way

The experts and the normal visitor view these buildings in very different ways.

The experts and the normal visitor view these buildings in very different ways.

Rachel Corbett

In 1959, Frank Lloyd Wright defended his design for the Guggenheim Museum from the charge that its curved architecture would subjugate the paintings inside: “On the contrary, it was to make the building and the painting an uninterrupted, beautiful symphony such as never existed in the world of art before.”

Today a curvilinear “symphony” is a hallmark of many starchitect-designed museums: the Baroque Museum in Puebla (designed by Toyo Ito), the Guggenheim Bilbao (Gehry), the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku (Zaha Hadid), the Fondation Louis Vuitton (Gehry), and the Milwaukee Art Museum’s Quadracci Pavilion (Santiago Calatrava), to name a few.

But is the public as charmed by all these bending, arching, sloping surfaces as the architects are who designed them? Not according to a new study published in the journal Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, which compared the architectural preferences of non-experts to those of professional architects and designers.

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Photo by Ian West/PA, Images via Getty Images.

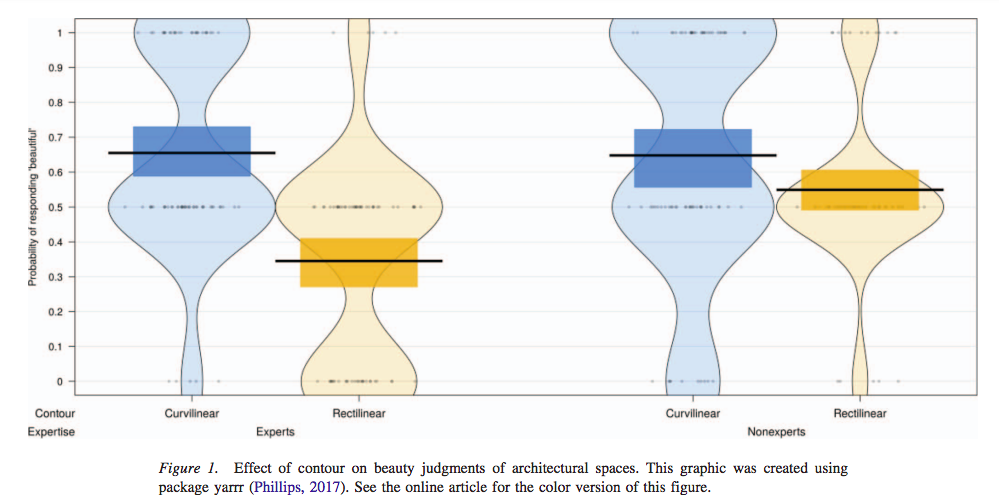

When asked to compare four images of curvilinear rooms with four rectilinear ones, non-experts—in this case a group of 71 university students who never studied architecture, interior design, or art history—showed no preference for one over the other. But those who self-identified as professional architects or designers consistently found curvilinear spaces to be more beautiful.

The researchers suggest that these taste differences could be the result of architectural training programs. “[A]mong experts, greater sensitivity to contour could be a function of negative associations toward rectilinear contours, honed through professional practice and training,” they write.

But a second part of the study adds an intriguing paradox to the findings.

The researchers went on to ask the participants how likely they’d be to enter each of the rectilinear and curvilinear spaces. And it turns out that non-experts were more likely to opt for the curved rooms than experts were. “The reason for this difference is not clear,” the researchers say.

They hypothesize, however, that it might come down to another effect of training: Even as the experts may have “honed” their eye to appreciate the spaces on the level of pure aesthetic form, they have also abstracted themselves from other kinds of positive associations ordinary people have with curvy architecture.

What are these? The paper argued that “we owe our preference for curvature to a coupling between this perceptual feature (i.e., curved configuration) and sensorimotor processes attuned to it in the brain.” That is, curves trigger an association with the feeling of movement.

“Perhaps when prompted to make an enter-exit decision, the functionality or usability of a space becomes the relevant frame for choice for non-expert participants,” the researchers write. “Experts may be trained to view images of architectural spaces dispassionately and be less subject to implicit behavioral biases rendered by their visual features.”

Thus, the real upshot of the study may be that architects do not sense the appeal of their own creations.

The Milwaukee Art Museum’s Quadracci Pavilion in Milwaukee.Photo by Jeff Greenberg/UIG via Getty Images.

The study is just the latest in a large ongoing body of research into the preferences of rectilinear versus curvilinear design. Previous studies have shown that infants look at round shapes for longer lengths of time than angular ones. Apes also have shown preferences for curved contours. And travelers have been found to favor rounded architecture at airports. But this study is rare in its focus on the role that expertise plays in these judgments.

In short, the public may not necessarily agree with Gehry that the Guggenheim is any more a “beautiful symphony” than, say, the boxy Brutalism of the Met Breuer. But, for reasons we’ll have to leave to a future study for now, they are still more inclined to go inside.