Analysis

Why Does the Art World Love Overlooked Artists?

The thirst for re-discoveries seems unquenchable.

The thirst for re-discoveries seems unquenchable.

Nicola Trezzi

There was a time, not too long ago, when collectors would go to young galleries, or directly to the artists’ studios, and buy works from emerging artists who would then go on to become the next big names of their generation: whether it was advertising magnate Charles Saatchi in London in the 1990s, Swiss ambassador to China Uli Sigg in the ’80s, or post-office employees and librarians Herbert and Dorothy Vogel in New York in the ’70s.

That seems like a distant memory now. The current state of the art moves at a much higher speed; though there are a lot more collectors around, you can count the risk-takers on one hand, while young artists, from all over the world, are ever more involved in complex and expensive productions. Galleries have to keep up with the costs connected to art fairs, which have become the privileged platform for selling and buying art by living artists.

This current scenario sees young artists going up in prices so quickly that it’s become difficult, if not impossible, to buy them continuously throughout their career. That’s especially true for public museums, that usually rely either on public funds—which are shrinking—and committees, whose decision-making processes will always take longer than those of deeper-pocketed private museums.

Roman Ondak, Loop (2009). Courtesy of Galerie Martin Janda

One of the most fruitful solutions to this dilemma has been the focus on overlooked historical artists. Through this strategy, museums can actually afford high-quality art at lower prices and avoid having to fight to obtain works by expensive emerging artists whose place in the history of art hasn’t been established yet.

The rediscoveries generally tend to fall into one of four categories, the first being “the artists’ artist”—seminal figures within the artistic community who were never recognized by the system. The second consists of historical artists from the so-called periphery and includes artists established in their own, off-center countries. The third is the autodidact or outsider, artists who never fit a certain scene. The last category relates to gender: artists who happened to be women.

Obviously these categories are flexible and they often intertwine.

This is the case—a combination of the first and second category—of Czech artist Jirí Kovanda and Slovak artist Július Koller, who were highly regarded closer to home, but pretty much unknown internationally, until younger artists such as Czech Ján Mančuška and Slovak Roman Ondák began to garner international recognition and at the same time started to promote them, securing a solo by Kovanda at Mančuška’s gallery Andrew Kreps (alongside a solo at the now-defunct Wallspace) and Koller’s representation by Ondák’s gallery gb agency (they also represent Kovanda).

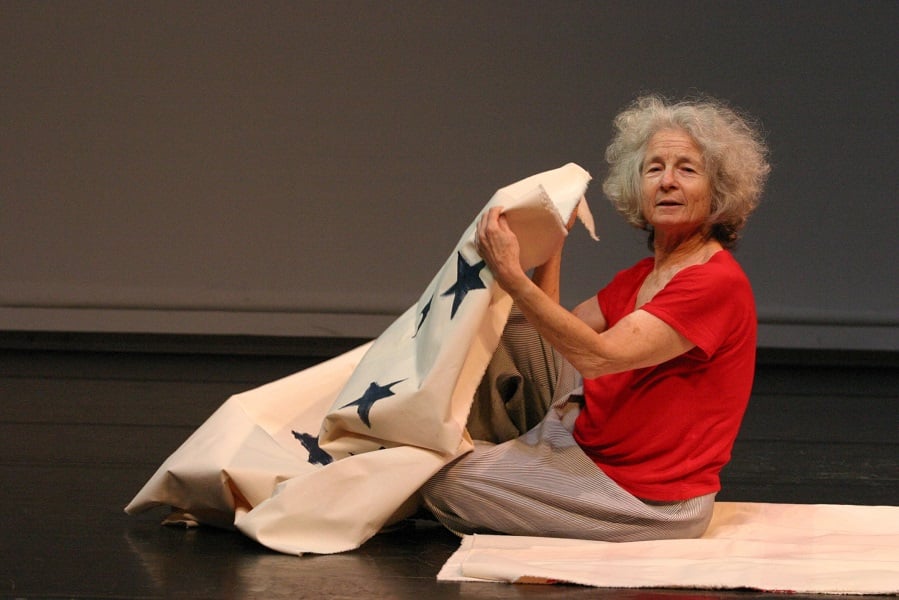

A similar trajectory—this time a combination of the third and forth categories—can be seen with Lee Lozano or even more so with Simone Forti, who, due to self-imposed exile (Lozano) and a focus on immaterial practice (Forti) had to wait many decades to see themselves presented next to male artists from their own generation such as Sol Lewitt, for Lozano, and Robert Morris, for Forti.

When Kaspar König urged legendary Cologne dealer Konrad Fischer to show Hanne Darboven, so the story goes, he could only be persuaded to do so in pairing with artist Charlotte Posenenske because staging a solo show by a female artist was too risky, even for a radical gallerist like him. At that time “women were on principle not regarded as equals” writes Anette Kruszynski in the exhibition catalogue of “Cloud and Crystal: The Dorothee and Konrad Fischer Collection” currently on view at K20 in Düsseldorf.

Simone Forti. Photo: Movement Research.

Increasingly, due to the aforementioned conditions, many institution—reluctant to step outside the canon until recently—are giving generous space to historical, yet lesser-known artists. Take for instance the recent acquisition and display of a monumental work by Romanian artist Ana Lupas at Tate Modern in London, which also recently acquired two works by Hungarian veteran Imre Bak (whose prices doubled in the last few years).

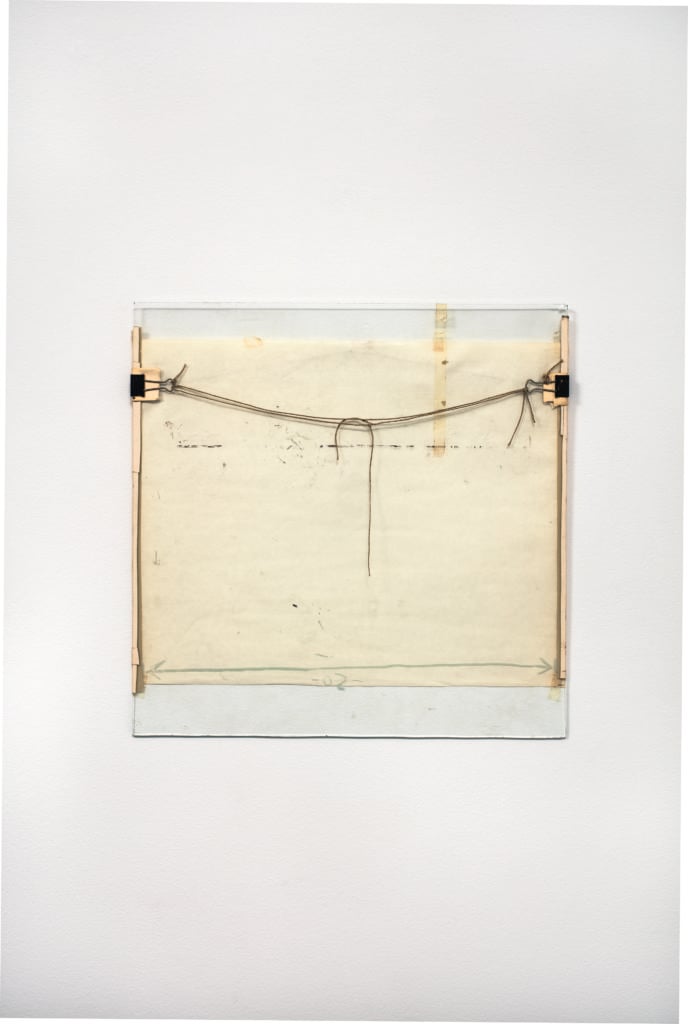

Currently on view is also a solo show of glass works by Israeli artist Nahum Tevet, curated by Duchamp expert Thierry De Duve for the Hunter College Gallery in New York. Next year Tevet will also show at Villa Stuck in Munich alongside his compatriot Efrat Natan, rediscovered after her retrospective at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem this summer.

Paris-based Lebanese artist Simone Fattal got her due at the Sharjah Art Foundation; and New York-based Iranian artist Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian was given her first institutional show in the US at the Guggenheim Museum in New York last year.

Even the Whitney Museum of American Art is stretching its national focus in order to show (a sign of current geopolitical changes?) Cuban-American, 101-year-old minimalist Carmen Herrera.

While art fairs as different as Frieze in London and Artissima in Turin both have sections devoted to historical artists and overlooked figures, commercial galleries of different kinds and sizes are adjusting their program to cater to this new market: Polish avant-gardist Edward Krasinski is promoted by Foksal Gallery Foundation and now shown at the Tate Liverpool; and Italian outsider Carol Rama—beloved by visionary dealers such as Isabella Bortolozzi and Michele Maccarone—is the protagonist of a traveling retrospective at MAM/ARC in Paris, MACBA in Barcelona, and GAM in Turin.

Nahum Tevet, Untitled #7 (1972). Photo by Polite Photographic, courtesy of the Hunter College Art Galleries and the artist.

Another strategy to introduce new old names to the market is to give context to works by historical artists from the so-called “periphery” by showing them alongside historical artists from the so-called “center.” A fine example for such pairing would be the decision of Barbara Gladstone to bring “Requiem for the Sun: The Art of Mono-ha”—originally presented at Blum & Poe in Los Angeles in 2012—to her gallery in New York that same year.

For Gladstone, the show made sense in the context of her position as the most important—together with Marian Goodman—American gallerist of Arte Povera, a movement which is always mentioned to contextualize Mono-ha beyond the history of Japanese art.

But giving new context to hidden gems is just one strategy. P420 in Bologna specializes in artists from the ’60s and ’70s such as Darboven, Irma Blank, Czech Milan Grygar, Croatian Goran Trbuljak, and Lupas. Hauser & Wirth represents lateral figures of Italian art such as Fabio Mauri and Fausto Melotti, and shows the late Japanese artist Tetsumi Kudo—represented by Andrea Rosen but beloved by H&W artists Allan Kaprow, Mike Kelley, and Paul McCarthy.

Furthermore, gender is less of an issue nowadays, both for artists and for gallerists. Alison Jacques in London represents female historical artists such as Blank, Brazilian Lygia Clark, Czech Maria Bartuszová, Austrian Birgit Jürgenssen and “American in Paris” Sheila Hicks. Broadway 1602 in New York, run by curator-turned-gallerist Anke Kempkes, has made its name through the representation of seminal and yet-to-be-canonized figures such as American Rosemarie Castoro (who’s getting a retrospective at MACBA next year), New York-based artists Sylvia Palacios Whitman and Babette Mangolte, as well and Pierre Restany’s protégés Evelyne Axell and Alina Szapocznikow.

In short, the formula seems to be working, and more and more dealers have such artists on their rosters, especially because historical figures often provide a rich inventory.

Tetsumi Kudo, Meditation Between Memory and Future(1978). Courtesy of Hiroko Kudo and the estate of the artist.

But perhaps the most striking example of the potential of such discoveries is indeed Szapocznikow, whose estate is now handled by Andrea Rosen.

It was 2007 when German Kempkes mounted an exhibition of Szapocznikow at her tiny apartment-gallery on Broadway 1602, showing among other works Petit Dessert I (Small Dessert I) (1970-71), which caught the eye of Marie-Josée Kravis, president of MoMA’s board of trustees, and her husband Henry. The trace of this amazing development (including eight years of work with the estate, and many museum acquisitions) can be seen on the invitation of Szapocznikow’s 2013 posthumous retrospective—organized by WIELS Contemporary Art Centre, Brussels, and the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, in collaboration with MoMA and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles—which featured an image of Petit Dessert I.

But beside the aforementioned market implications, it is important to understand the critical implications of this phenomenon; while in the past the art field was run by a like-minded elite clustered in one geographical and chronological node—”easy to find but hard to penetrate”—the elite of today and especially tomorrow has a different, by no means easier, task. Because all the knots have been untied, the art of tomorrow is easier to penetrate but harder to find, due to the end of the center-periphery dichotomy.

In this scenario, where space has opened up, our perception of time should be adjusted, too. In other words, the new artists are not only those born in the nineties but also those approaching their nineties.