Auctions

Why Was Christie’s CEO Steven Murphy Fired?

Insiders point to zero profit for big ticket lots with huge guarantees.

Insiders point to zero profit for big ticket lots with huge guarantees.

Coline Milliard

The departures of major auction houses’ CEOs are like London buses: you wait forever for one to come and two turn up at once.

When Sotheby’s chief executive William Ruprecht announced he was stepping down two weeks ago, no one batted an eyelid. After all, the announcement came at the end of a long-winded proxy battle spearheaded by investor Dan Loeb, who had forced his way into the board and had Ruprecht in his sights (see “Will Dan Loeb Take Sotheby’s Private? Stock Rises 9 Percent on Departure of William Ruprecht“).

The departure of Christie’s CEO Steven Murphy is quite another story, however. An art world outsider when he took over the house in 2010, Murphy is largely credited for having radically modernized the London-based auction house, investing $50 million in the online platform and securing the company’s place in Asia.

The surprise announcement also comes hot on the heels of Christie’s glittering postwar and contemporary sale, which pulled in $852.9 million in New York last November (see “Epic Christie’s $852.9 Million Blockbuster Contemporary Art Sale Is the Highest Ever”).

Murphy is said to have been brought to the auctioneer by François Pinault’s right-hand woman, Patricia Barbizet, who has been appointed as his successor. (Barbizet is CEO of Pinault’s holding company Artémis, which owns Christie’s.) She claims that Christie’s “sales and profits [are] at their highest ever level,” but PR aside, what has really been going on?

Unlike Sotheby’s, which is publicly traded, Christie’s is a private company and doesn’t have to disclose its figures or any deals it makes with collectors to secure prime consignments. These deals include the ever-more-regular guarantees on results (which pay out regardless of the outcome of the sale), as well as, in some cases, a forgoing of the commissions and of part of the buyers’ premium.

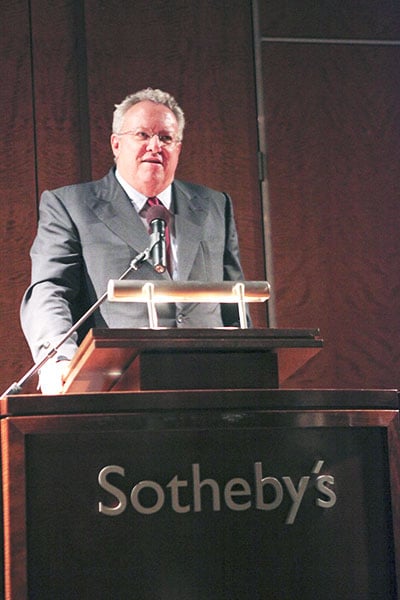

Former Sotheby’s CEO William Ruprecht.

Photo: Shaun Mader/patrickmcmullan.com

Some of those deals have left the house sideways, most publicly with Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Orange). Despite it setting a record for the most expensive work by a living ever sold at auction in 2013 ($58.4 million), its former owner Peter Brant and the house reportedly agreed that, if it didn’t hit $75 million, Christie’s “shouldn’t get anything.”

According to auction house executives in Miami for Art Basel, multiple cases in which guarantees on major lots garnered heavy media attention but no profit for Christie’s resulted in Murphy being pushed out from his post as CEO.

“You’ve got two CEOs who’ve been battling madly for market shares and their margins seem, by many accounts, to have got smaller and smaller,” commented an industry insider who spoke to artnet News on the condition of anonymity. “So in one case, a slightly aggressive, disrupted board, and in the other case a company owner, appear to have said ‘enough is enough’.”

“We are at a record time for the art market, but it seems these two have battled so hard they might not have turned that into record profits,” she added.

But, not everyone is buying it. Thomas Seydoux, former co-head of Christie’s Impressionist and Modern Art department, says such conclusions are “a little too quick.”

“Even if it’s a very competitive environment, even if one has to make concessions on the commissions, even if the profitability isn’t optimum, when you do a $850 million sale, you make money,” Seydoux told artnet News. “Let’s not forget that not that not that long ago, contemporary art sales didn’t reach $100 million. This is eight times more.”

Seydoux suggests that Murphy’s departure was in fact always part of the plan. “I think that Murphy’s work was clearly transition work, which is never popular, and never easy,” the Christie’s veteran said. “Usually restructurings of the kind he implemented don’t come with a permanent post. One prefers to have someone very professional deal with the change, and then appoint someone else to make peace with those who didn’t like it. It’s probably what happened.”

Yet even if it was a plan all along, the timing is odd. Not only did the news come as the art world gathered in Florida for Art Basel in Miami Beach, but it also coincided with two important Christie’s sales: Contemporary Art in Paris, and Old Masters in London. Murphy also pulled out of a luxury goods conference being held in Miami in conjunction with Art Basel at the 11th hour (see “François-Henri Pinault Says Fashion Should Not Exploit Art for “So-Called Respectability”“).

So either Pinault’s team decided to let Murphy go sooner than expected for some unforeseen reason—which seems to be the more popular explanation among art worlders—or else the CEO pulled the rug from under Pinault’s feet and decided to leave.

The need to move quickly would explain the appointment of Barbizet, who has been Pinault’s loyal aide since she joined the group in 1989. But she already has plenty on her plate. Barbizet is CEO of Financière Pinault and Artémis, vice-chair of the board of Kering (Pinault’s luxury goods holding company), and an independent director for such major French groups as Total, Air France/KLM, Bouygues, and TF1.

“Does she really want to throw herself into Christie’s? That I don’t know,” said Seydoux. “It hasn’t been her profile up to now. It’s up to her, but I imagine that [the appointment] could be temporary.”