Market

Artist William Powhida Doesn’t Have Room to Store All His Work—So He Wants You to Borrow It, for Free

“I am proposing something between letting go of work for free and trying to sell it on consignment," the artist says.

“I am proposing something between letting go of work for free and trying to sell it on consignment," the artist says.

Taylor Dafoe

A couple of years ago, the artist William Powhida had just downsized to a smaller Brooklyn studio when his West Coast dealer returned a bundle of works that had been sitting in the gallery’s storage. The works immediately annexed a corner of his workspace, where real estate was already tight.

“These boxes came back and I realized that this work had been sitting boxed up, unseen for years,” the artist tells Artnet News. “It opened up this idea of, ‘Well, what if I was able to place this work with somebody, but without giving up hope that there might be some potential resale value for the work or some economic value to it?’”

His answer came in the form of both a practical solution and a new, quasi-conceptual artwork unto itself.

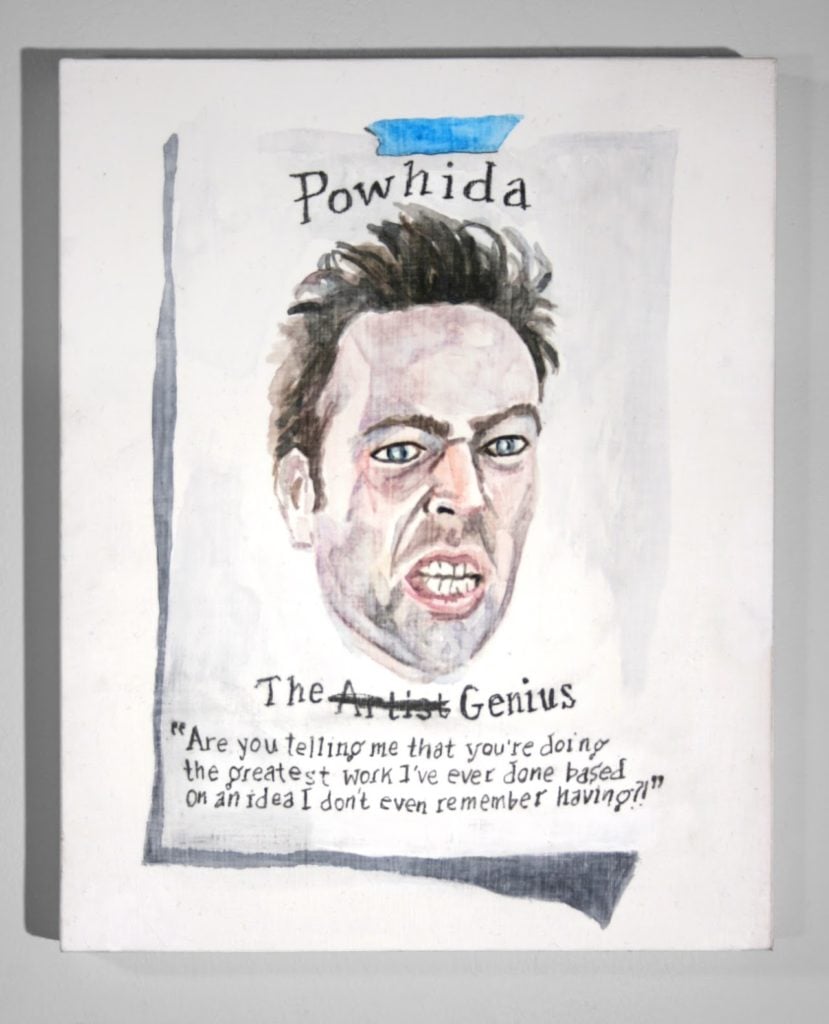

William Powhida, I Statement 3 (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

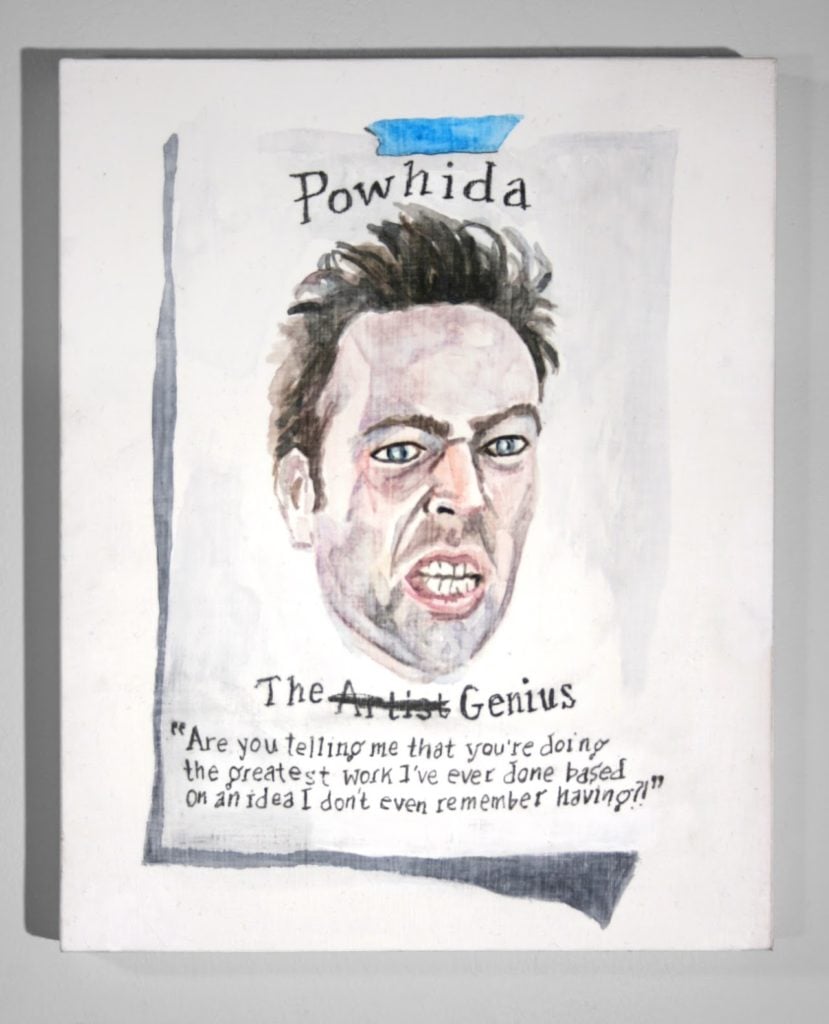

Through a newly-launched initiative called Store-to-Own, Powhida is inviting strangers to freely borrow artworks from his personal inventory to keep in their homes or offices. For the artist, the project offers free storage for his work in a place where it will actually be seen and appreciated. For borrowers, it’s free art that might otherwise come with four- and five-figure price tags at his galleries, like Postmasters and Charlie James. All borrowers have to do is take care of it.

Known primarily for his illustrations that merge Raymond Pettibon-like graphics with cheeky institutional critique, Powhida doesn’t have the storage concerns of, say, a sculptor working in Corten steel. But his inventory of old works took up valuable space, both physically and emotionally.

“Storage is an issue that we don’t often discuss in the art world,” Powhida writes on his website. “Unsold inventory represents a heavy financial and emotional burden for artists and galleries tied to the potential, perhaps theoretical, value of the works.”

“I am proposing something between letting go of work for free and trying to sell it on consignment.”

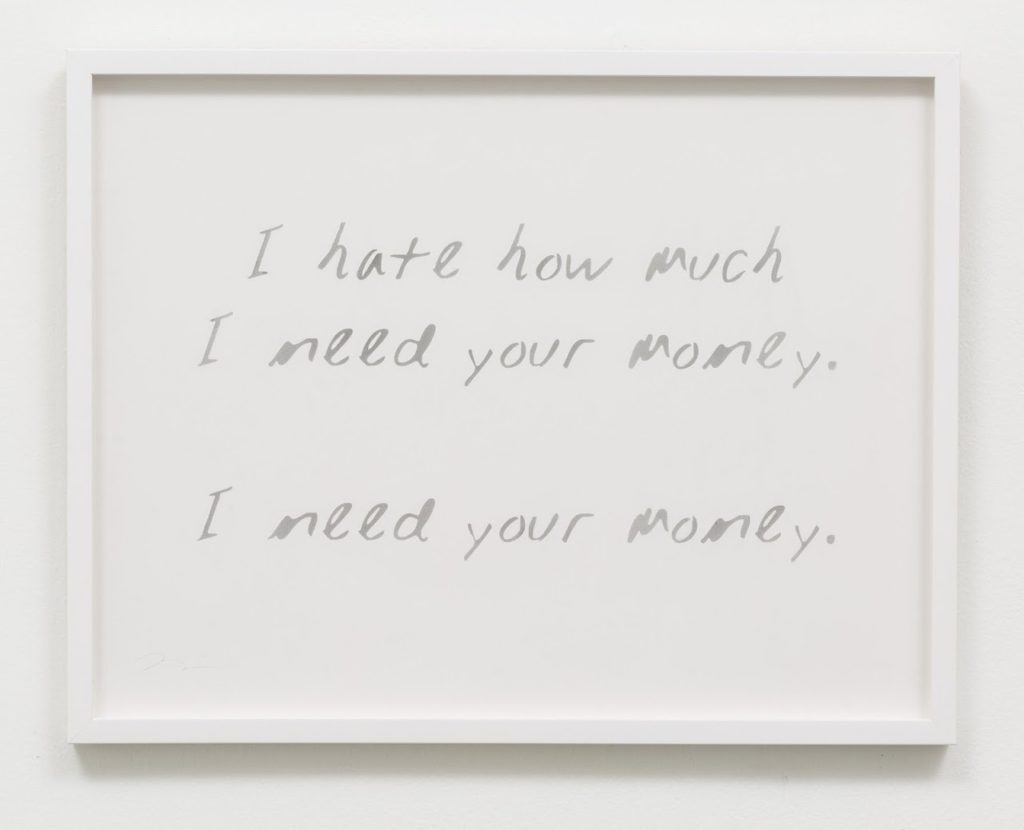

William Powhida, Fuck Trump (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

To borrow one of Powhida’s works, you simply apply through an online inquiry form. If accepted—and so far, just about everyone who has applied has been accepted—the artist will shoot you back a contract that he put together with fellow artist Alfred Steiner and writer-professor Amy Whitaker.

It stipulates that the borrower is responsible for caring for, storing, and insuring the artwork. The borrower may at any time purchase the work, and the price to do so will go down by 20% with each year they’ve held onto it. After five years, outright ownership of the artwork will be transferred to the borrower.

The borrower may also sell the artwork at any time—and for any price—though Powhida will be owed 50 percent of the profits. The contract also includes a 10 percent resale royalty clause, meaning that should the artwork appreciate in value, the artist will continue to make money on it.

“Being confronted with boxes and boxes of stuff in this unsold inventory prompted me to think about how I can actualize some of these ideas I’ve been thinking about—about how we value art through price points and how ownership is one of the prime conditions of contemporary art.”

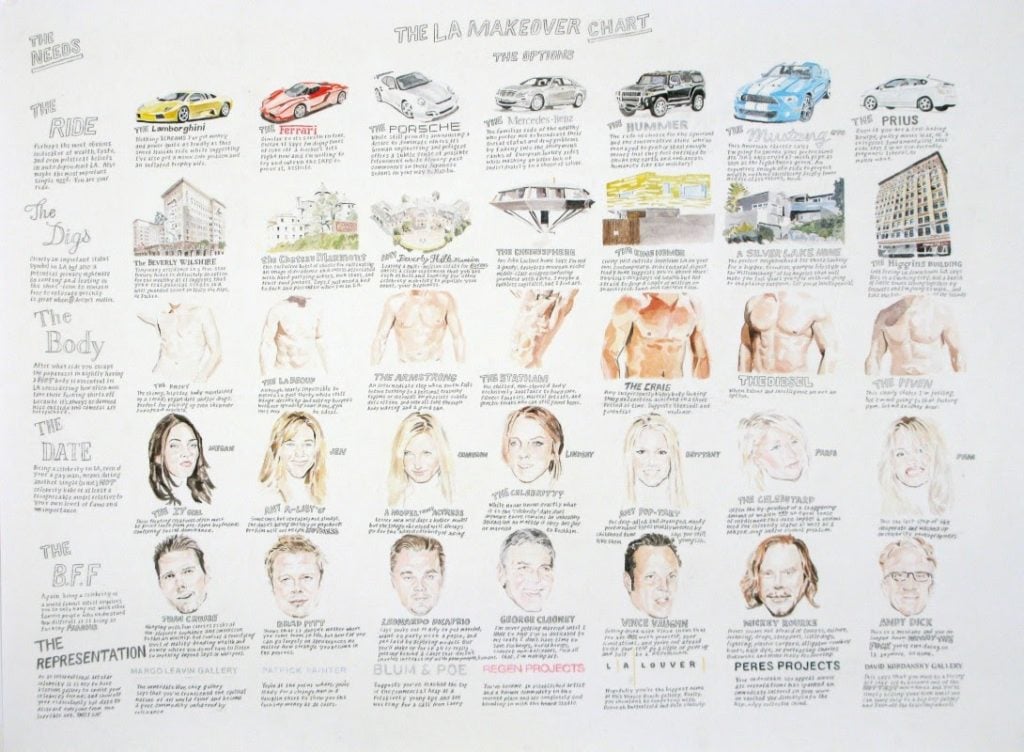

William Powhida, L.A. Makeover Chary (2015). Courtesy of the artist.

A free, alterable version of Powhida’s contract is available for download on his website, and he encourages other artists to use it for their own work. It helps, he says, in preventing one from being sucked into “believing you’ve not succeeded if you have a significant inventory.”

“I think that’s part of the reason people don’t want to talk about this,” he explains. “It’s like, ‘Hey, do you want to look at my stack of unsold toasters over here?’”

See the full inventory of Powhida’s borrowable works here.