Art Fairs

Free to a Good Home: Artists Launch a New Fair to Clear Unsold Works From Their Studios

Collectors must agree to a five-year vesting period in the "sale" contracts.

Collectors must agree to a five-year vesting period in the "sale" contracts.

Adam Schrader

The Zero Art Fair, a new three-day affair in upstate New York, uniquely allows artists to clear out their storage spaces by giving works away free to would-be collectors who normally couldn’t afford them.

The concept for the fair is rooted in a contract first developed by the artist William Powhida in 2019. At the time, Powhida had received a large amount of work back from his gallery in Los Angeles. His Bushwick studio was too small to store it all. He has since partnered with fellow artist Jennifer Dalton to create Zero Art Fair, which will be held in Elizaville in July.

“The shows did well, but I had 30 or 40 objects I was looking at and wondered if there was a way I could give them away while experimenting with some ideas,” Powhida said. So he reached out to another friend to help him draft a contract.

Under the terms of the contract, ownership is transferred after a period of five years if the work hasn’t sold. During that time, the borrower retains possession of the work but it remains fully sellable by the artist. At any point after ownership is transferred, the artist would be entitled to 50 percent of the profit if the work sells.

“I knew I was pretty much going to be giving this work to people, but I wanted to create space in my studio,” he said. “The other thing was, you know, this work had a chance to sell. It was in inventory for a long time.”

Artists and fair organizers Powhida and Dalton shift artworks in storage. Photo: Adam Schrader.

Powhida said the market is structured to prioritize the sale of new work and so he didn’t think the work would be shown again. So, he took the contract to another friend, a lawyer, who helped make it more legally enforceable in New York State.

With that contract in hand, Powhida started a website advertising his store-to-own concept. He got 400 requests to take his work off his hands in just two days.

“I was the canary in the coal mine because next year, in 2025, the vesting period for my contracts ends and ownership of the work will automatically transfer to them,” Powhida said. “I’ve had two conversations with any of the people who took the work about the work they have. There hasn’t been one instance where I needed to borrow the work back. I’ve not heard anyone say, ‘Oh, your work was destroyed.’ Nothing has come up at auction.”

When Studios Become Storage Units

One of the seeds that led to the project came from the artist Jade Townsend, who once told Powhida they had spent about $60,000 storing artwork over the years and ultimately did a garage sale to liquidate their storage unit. Another friend, Peter Rostovsky, said he felt like he had to choose between having a studio and having a storage unit.

“Artists can’t stop making work,” Dalton said. “I often say that if I could stop, I would. But it’s a compulsion and no matter how much of the work is selling, I’m still going to make more.”

Dalton, who co-runs the Auxiliary Projects gallery in Greenpoint which aims to sell works at affordable prices, added that it’s “uncomfortable” for artists to talk about getting rid of their work or discuss the market conditions that prevented their work from selling.

“Giving your work away is not a sustainable answer to the problems with the market system,” she said. “We feel like the bar is low for trying out other experimental ways of doing things.”

The idea of giving away artwork is not necessarily new, Powhida pointed out. In 2006, Adam Simon developed this website called the Fine Art Adoption Network—a platform where artists could let work be “adopted.” But what Simon’s project didn’t do that Powhida thought he could bring was the use of the contract to let artists retain certain rights.

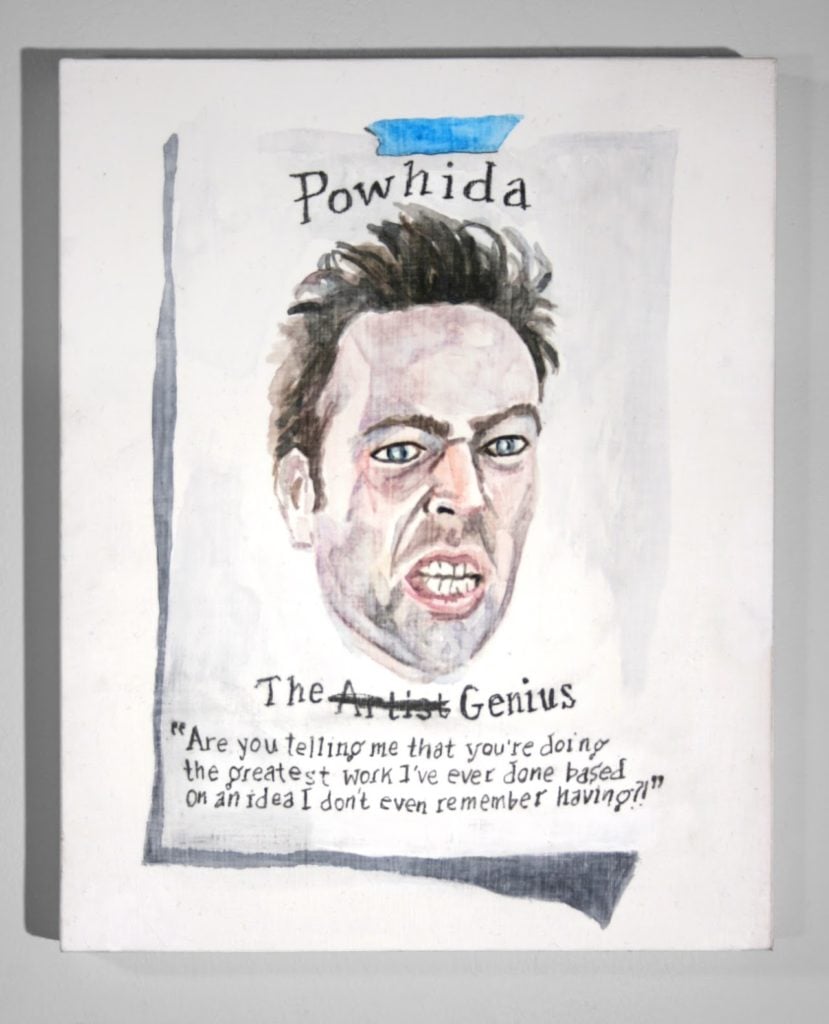

William Powhida, Powhida (2007). Courtesy of the artist.

“We’re not totally giving up on the value, or the possibility that somebody could sell the work later,” Powhida said. He added that he and Dalton previously did a project called #Rank in Miami, there was an artist named Sean Naftel gave away 150 pieces of free art by the end of the day amid the high-value Art Basel Miami fair.

“That was uncomfortable because we were inside an art fair,” Dalton added. She explained that the discomfort artists have with the market comes for two reasons: either they are not successful in the market or they’re selling work to people that are in a different economic class.

“Most artists don’t sell a lot of work and have ancillary income from day job,” she said. “But they price their work because something takes them months to make, and they can’t really sell it super cheap. So then that price is either a theoretical price, like the market is kind of a fiction, or they’re selling it to people in an entirely different class.”

Powhida has seen examples of rent-to-own arrangements where clients could pay to rent an artwork for a period with the option to buy it at a discounted rate in the future. And Dalton added that artists sometimes have studio sales where they note that the retail price might be $10,000 but offer works with deep discounts.

“But I haven’t necessarily seen too many things like this or that use a contract to kind of facilitate or set up a framework for the exchange or transfer work,” Powhida said.

Keeping the Fair Fair

When asked whether they feared that everything might find a home in the first day of the three-day Zero Art Fair, the duo noted that they have a limit of one artwork per collector per day to keep things fair.

The organizers are still in the planning phase for this year’s inaugural fair and are holding an open call for artists through May 20. They are asking for up to five works from each artist with the expectation that about three works from each artist would be approved. They aim to hang about 100 works per day with the goal of having empty racks by the end of the fair.

Dalton and Powhida said that the art market “doesn’t work for the majority of artists.” Photo: Adam Schrader.

Dalton expressed that the logistics of the fair have proven difficult because the team doesn’t have a staff and has only raised a budget of about $7,000. And because the fair’s mission is to give art away for free, there’s no profit in running the show.

“It’s not nonprofit, but it is no-profit,” she said.

The team is sensitive to the idea of asking for volunteers to help run the show because they are already asking artists to give their work away for free.

“We are looking for somebody who has experience working at art fairs that could kind of help us with logistics,” Powhida said. “If we do have some volunteers to move or help pack things, that would be amazing.”

When asked if the fair could be gamed by wealthy collectors and dealers who may be looking to pick up some works on the cheap, Dalton noted that they are welcome to come—”we’re not asking for their tax returns or anything”—but the team will maintain a public online ledger of the of the new collectors and the work that is matched with them. Flipping is discouraged via the five-year vesting period in the “sale” contracts.

Powhida added that the fair is considering having tiers to fundraise the operations of the fair. For example, for $500, a collector can be among those who get first dibs of the available works before access is given to the public.

Dalton and Powhida also addressed concerns that a free art fair could be used by savvy collectors and galleries to game the market of a rising artist.

Getting Artists Paid

Conceptually, the idea of the fair is that works will retain value, but statistics from the Art Basel 2022 market report show that 68 percent of all works sold by living artists on the secondary market was under $5,000. And that’s just the work that makes it to auction. The report also shows that 57 percent of gallery sales are driven by the gallery’s top three artists. The top artist at a gallery usually drives 43 percent of a gallery’s sales.

“When we say things like ‘the art market doesn’t work for the vast majority of artists,’ it is because there’s a lot of value and activity at the lower end of the market, but it’s generally these very low-price points and it’s spread out amongst a ton of artists,” Powhida said.

While the fair aims to send people home with free work, they hope the works do sell in the future so the artists eventually get paid.

“Even during the fair itself, somebody could just say, ‘I’m going to buy that, and I don’t want to deal with your contract.’ But they’ll have to pay for that privilege,” Powhida said. But he doesn’t believe there’s a big risk the free fair will turn into a rush of people trying to buy art because “it doesn’t sound like human nature.”

“We’ve had to think about what our role is. Are we sort of representatives to the artists? Should we be trying to facilitate sales? We don’t really want to get into that zone,” Powhida said. “If somebody said I wanted to buy it, we’d have to put them in touch with the artist.”