Galleries

World’s Biggest Art Review: 7 Critics Cover 20 New York Gallery Shows

Join artnet News' team of critics and reporters on the gallery beat.

Join artnet News' team of critics and reporters on the gallery beat.

Artnet News

Julião Sarmento at Sean Kelly Gallery, closes May 3.

Taste a little sensuous pleasure here, courtesy of pale, elegant paintings of geometric shapes and forms. For the artist this is nothing terribly new, though a conceptual conceit gives more to chew. The show is structured as a fictitious relationship between Degas and Duchamp, the artist searching to combine their influences and legacies in paintings and a singular installation-sculpture. An admirable, even impossible goal, I suspect, to join the purveyor of pure and sublime aesthetics with the master of concepts. Sarmento is searching for the Holy Grail of art.

Benjamin Genocchio

“Alexander The Great, The Iolas Gallery 1955–1987” at Paul Kasmin Gallery, closes April 26.

Time traveling is provided at the Paul Kasmin Gallery, where you can step into the world of the Iolas Gallery, a trendsetting enterprise from the mid 1950s to the late 1980s. Against deep purple walls (yes, I know), two dozen works of modern art offer gentle endearment for those willing to recall the genius of Max Ernst, Roberto Matta, Jean Tinguely, Ray Johnson, Alain Jacquet, Dorothea Tanning, and Jannis Kounellis. A handful of Ed Ruscha paintings hint at changing times, but mostly this show is a glad reminder of how good so much postwar 20th century art was. Keep on looking.

Benjamin Genocchio

François-Xavier Lalanne, Lapin Polymorphe (moyen) (2006).

Photo: Courtesy Paul Kasmin Gallery.

Caroline Wells Chandler at Field Projects, closes May 10.

You will not find a more delicious, demented, formally and emotionally fulfilling exhibition in Chelsea this spring than Chandler’s “Homunculus,” and not only because it mostly consists of wall sculptures depicting nightmarish, psychedelic cookies loaded with perfectly-replicated toppings like M&M’s, marshmallows, Hershey’s Kisses, Skittles, Cheerios, and other assorted staples of an American child’s (or stoner’s) diet. The titles, like Selfie as Alien Milk Dud Cookie and Selfie as Green Slimy Cookie with Nerds (both 2014), up the uncanny by highlighting the relatively untapped sub-genre of baked goods self-portraiture. In addition to the nearly 40 cookie sculptures crammed into the tiny gallery, four crocheted, Muppet-like figures lie sprawled on the floor, propped in the corners, or curled up in the fetal position as if in the throes of a really harsh sugar trip. Chandler’s OD-ing cookie monsters and ominous monster cookies are simultaneously endearing, delightful, repulsive, and weirdly appetizing—and among the most aesthetically nutritious works I’ve seen all year.

Benjamin Sutton

Christine Meisner at the Walther Collection, closes May 24.

Something like an epic poem with a blues score, Meisner’s 28-minute video Disquieting Nature (2014)—the exhibition’s centerpiece—features her own lyrics and nearly static black-and-white interiors and landscapes shot around the Mississippi Delta region in 2011 during a six-week road trip tracking the diffusion of blues, set to music by William Tatge. Interspersed in the video are aerial, practically abstract drawings of the Delta landscape criss-crossed by grids of roads and meandering rivers. As a contrast and complement to the ponderous and moving video, Meisner has included exhaustive sketches, notes, and diagrams created during the trip and afterward; they plot her journey, the history of blues, the diffusion of African cultural practices across the Americas, and other charged and many-tentacled movements.

Benjamin Sutton

“Panopticum” at Robert Miller Gallery, closes April 12.

There’s a great deal to be enjoyed in writer-curator Kevin Moore’s thematic show of works probing our culture’s collective forensic, anatomical, and taxonomical impulses, whether in the rogue biological projects and related drawings of Mark Dion, Taryn Simon’s arresting photo of a cosmetic surgery patient mid-hymenoplasty, or one of Cindy Sherman’s creepiest large-scale images of a dismembered and dirt-smeared doll. The exhibition’s star attraction should be a series of Herbert List photographs from 1944 starring unsettlingly pretty late-19th century surgical dolls from Vienna, their innards exposed. But Jonah Freeman and Justin Lowe’s enormous rear-room installation Profanity in the Sky (2014)—a seemingly looted secondhand store with a smattering of portentous and odd objects left behind that is accessed through the hole smashed in the wall next to the Michaël Borremans painting—overshadows everything else with its surprising size and impressive level of whimsical detail. So what if it’s a little off-topic?

Benjamin Sutton

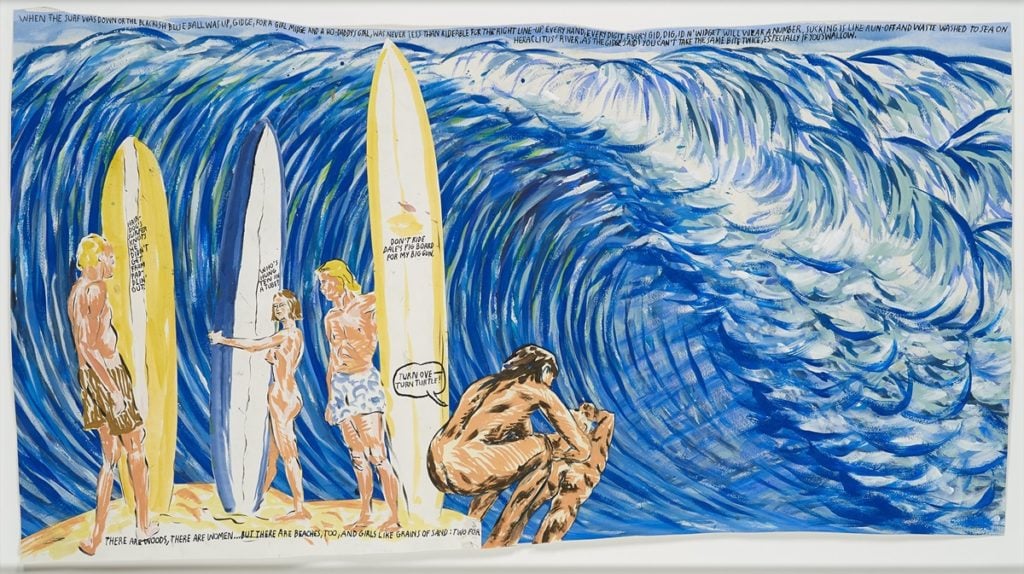

Erwin Wurm, Kiss (Abstract Sculptures), 2013.

Photo: Benjamin Sutton

Erwin Wurm at Lehmann Maupin, closes April 19.

Never one to take himself too seriously, you can’t help but wish that the Austrian artist had gone the extra mile and legally changed his last name to “Worm” so as to be in keeping with the incredible number of sausages, bratwursts, wieners, and other assorted phallic things that he has cast in bronze and acrylic to create the sculptures in his new show. Giggle-inducing works like Head (Abstract Sculptures), Step (Abstract Sculptures), and Kiss (Abstract Sculptures) (all 2013) are exactly the type of thing Giuseppe Arcimboldo might have made, if he’d been a New York City hot dog vendor. Though not as hilarious, the non-sausage works in “Synesthesa” are similarly adept at aping the forms and proportions of classical sculpture all the while subverting them to comic effect.

Benjamin Sutton

Richard Patterson at FLAG Art Foundation, closes May 17.

This mini-survey from the British-born, Dallas-bred artist is a study in Americana, combining countless art historical, cinematic, and Freudian references. From a painterly portrait of a Dallas Cowboys Cheerleader to a surreal scene from Midnight Cowboy, the show is a peek into the mind of the artist—a place populated by beautiful women, motorcycles, and plastic army men, all awash in globs of colorful paint. With a great sense of humor and no shortage of kitsch, this is a show to see if you appreciate art with (possibly) more meaning than meets the eye.

Cait Munro

“Logical Guesses” at Driscoll Babcock, closes April 26.

Featuring works by Sol LeWitt, Marylyn Dintenfass, Alice Hope, and others, this show succeeds due to the unique intricacies of several pieces—for example, a bowl constructed entirely of matchsticks by Ryan and Trevor Oakes. Although not mind-blowing and a bit disjointed as a whole, many works merit a second, closer look in order to realize their physical complexity.

Cait Munro

Ryan and Trevor Oakes, Matchstick Dome, 2013.

Photo: Cait Munro.

Ghada Amer at Cheim & Read, closes May 10.

Airy and colorful on the surface, Amer’s embroidered “paintings” are engaged in a deep exploration of the complexities of the modern woman. By combining written statements like “One is not born but rather becomes a woman” (a quote from Simone de Beauvoir) with large portraits of girls wearing come-hither expressions (often sourced from soft-core porn magazines), the artist plays with our notions of image/text, high/low, male/female, and art/craft in a way that is both thought-provoking and visually striking. Just as enjoyable are Amer’s egg-like metal sculptures, which carry the same themes into a new medium that she is just as capable of deftly manipulating.

Cait Munro

Adam Pendleton at Pace Gallery, closes May 3.

The undeniable centerpiece of this multimedia exhibition is the video, My Education: A Portrait of David Hilliard, an interview in which the former Black Panther leads the viewer on a tour of an Oakland neighborhood, recounting a fatal gun battle that took place two days after the death of Martin Luther King. Using unexpected camera angles projected upon three separate screens, the artist has created a space that is quiet, contemplative, and ultimately worth its subject. In a second room, large mirrors splattered in silkscreen ink are pleasurable, but feel flat after the harrowing video experience.

Cait Munro

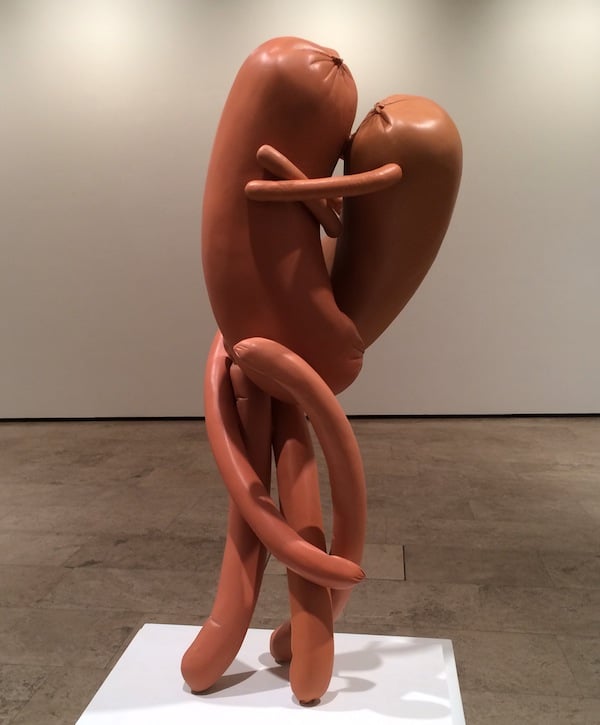

Sarah Lucas, Chicken Knickers, 2014.

Photo: David Regen © Sarah Lucas, courtesy Gladstone Gallery,

New York and Brussels.

Collier Schorr at 303 Gallery, closes April 12.

Of the photographs of mostly nude women in this exhibition, one is sliced into five parts and pieced back together, another is unframed and pinned up with binder clips, and yet two more are rolled and placed in a Plexiglas vitrine, making it difficult to get a good look at their bodies. As with their presentation, the subjects of Schorr’s lens, though they seem at first like female models in tear sheets from Vogue or Harper’s Bazaar, are equally hard to grasp—they’re not easily objectified (though they’re half-naked and posed as if they want to be looked at), sometimes they look away from the camera when they should be looking at it, and you’re not sure most of the time if they’re men or women; and then you feel conflicted for even having wondered. (Calling the show “8 Women” was coy, to say the least.) This is the weird bind you might find yourself in while viewing Schorr’s smartly handled images in this captivating show.

Rozalia Jovanovic

Friedrich Kunath at Andrea Rosen, closes April 26.

Plush blue carpeting muffles the sound of your steps as you walk into Friedrich Kunath’s exhibition. As if that wasn’t loopy enough, there’s a set of what appear to be very tall cat-scratching posts covered not in regular carpeting, but in the kind of Persian rug favored by Sigmund Freud. On the platforms of these psychoanalytic cat scratchers (or, as Kunath names them, “Melancholy Towers”), instead of cats, there are outsize sculptural fruits adding a touch of exoticism, not to mention humor, to this alluring medley of concerns. Lining the walls, canvases painted to look like notebook paper with pencil and charcoal drawings on them, offer windows onto beautifully painted scenes of impossible dreamscapes. Other large canvases offer bright bands of color with small carefully painted objects. Expect to be surprised by the idiosyncratic feel of Kunath’s show.

Rozalia Jovanovic

Sarah Lucas at Gladstone Gallery, closes April 26.

Sarah Lucas’s characteristic ribald wit is plentiful at her first US exhibition in almost a decade. Rooms are filled with enormous sculptures of cast-concrete phalluses balanced against rectangles of crushed cars and equally huge bronzes of vegetables that in this context come off as sexually suggestive. There’s the sense that through size, this artist of the YBA generation can make up for the loss of shock value her work once registered. It’s the smaller scale, delicate, and ravishing bronze casts of stocking sculptures made to look like humans in repose—which could easily go atop any mantle—that are most alluring. The apotheosis should be in the back room, where the walls are covered in Eating a Banana (2014), wallpaper digitally printed with images of Lucas provocatively eating a banana, circa 1990, when the artist was newly emerging with her fellow YBAs. But rather than startling, the effect is more one of nostalgia for artwork that at one time could be truly unsettling.

Rozalia Jovanovic

Kristen Morgin, Super Can Man (2013).

Photo: Courtesy Zach Feuer.

Kevin Appel at Ameringer | McEnery | Yohe, closes April 19.

What appear at first glance to be large abstract paintings primarily in shades of black, red, and white, are revealed on careful inspection to be Kevin Appel’s photos of Los Angeles construction sites. Blocks of concrete and profusions of rebar are almost entirely concealed by large translucent swaths of color and Ben-Day dots. The effect recalls Roy Lichtenstein‘s oeuvre, adding a cheerful pop sensibility to the city’s decaying urban landscape.

Sarah Cascone

Elger Esser at Sonnabend Gallery, closes April 26.

In the tradition of romantic landscape painting, Elger Esser offers a series of large-format photographs of Giardino di Ninfa, a lush, verdant Renaissance-era garden in the south of Rome. The romantic fairy tale quality that pervades the mythologically inspired works has darker, more sinister undertones: A tangle of branches ominously obscures your view of brightly colored flowers, something translucent and mysterious hovering in front of the camera leaves certain areas of the photo fuzzy and out of focus, and a strange, rectangular, almost fluorescent light in the sky gives off a haunting, otherworldly glow.

Sarah Cascone

Kristen Morgin at Zach Feuer, closes May 3.

Nothing is what it seems in Kristen Morgin’s “The Super Can Man and Other Illustrated Classics.” A master of trompe l’oeil, the artist has carefully painted unfired clay sculptures to perfectly mimic toys, books, records, household objects, and other items. Appearing rusted and decayed due to the passage of time, and defaced by painted “stickers” and writing, the sculptures are at once suffused with a sense of nostalgia and childhood whimsy, and regretful longing for time gone by. Juxtaposing Disney cartoons and retro pop culture icons with tin cans, wooden blocks, and assorted odds and ends, the show resembles nothing so much as your grandpa’s garage, chock full of the useless former treasures forgotten by a long-departed family.

Sarah Cascone

Urs Fischer, mermaid, 2014.

Gagosian Gallery © Urs Fischer, courtesy of the artist and Gagosian Gallery. Photo: Melissa Christy.

Urs Fischer at Gagosian Gallery, closes May 8.

It takes serious balls for an artist to do a Last Supper; It’s a pushy construct. Urs Fischer’s version, a take on da Vinci’s (as was Warhol’s), is a tableau complete with tacos, cigarette butts, rats, and all the usual apostolic suspects. Powerful, sly—Thaddeus seems to be patting Simon’s rear end—and seemingly slapdash, it takes place in Gagosian’s new Park Avenue storefront space like a doomed dinner party.

At its center sits Christ, wide-eyed and spiky-haloed, apparently overwhelmed—almost cartoonishly—by the melting rot surrounding him. He sits both together and isolated, as deep cracks in the bronze table maroon him away from his disciples.

Its tempting to be resistant to the art, given the sophistication and inexorability of its march to market. Consider Fischer: curated by the New Museum’s Massimiliano Gioni, introduced globally by Gavin Brown, collected by Peter Brant, sold by Larry Gagosian. (There’s more spontaneity in a square dance.) Sometimes it can seem like It’s their world, we just open checkbooks in it. That said, it’s pretty memorable work. Damn it.

Alexandra Peers

Urs Fischer at Gagosian Gallery, closes May 23.

Larry Gagosian’s latest presentation takes place in a Chase Manhattan Bank branch abandoned on Delancey Street. Distressed, by time or artifice, it displays several Urs Fischer sculptures among pockmarked walls, graffiti, gapingly open safe-deposit boxes, and the general faux-wood detritus of corporate life. The financial setting might have had more resonance in 2009, and verges on gimmicky, but ultimately works.

The art was made of clay in 2013 by Fischer and hundreds of volunteers, for a Los Angeles MOCA show. The best pieces from then have been cast in bronze, and this makes it a strikingly uneven show in scale and subject. But at the center sits a glorious mermaid fountain, all surface and sex, and the show radiates out from there into different rooms. It gives it all a theme park air that you don’t want to leave until you go on all the rides.

A gleaming cat sits in a closet; in the back room a giant foot lands like it smashed through the ceiling, Monty Python style. There is a literal pig*ucker, melting Grecian columns, a gleaming, tiny silver bed. There are riffs on Koons and Warhol, maybe even Botero. It’s a show of ruins and scenes. It’s cool.

And if we should care that it seems the exhibition has essentially come straight on flatbed trucks from museum to marketplace, well, welcome to the art world.

Alexandra Peers

Maureen McCabe, Blue Ionia (2013), mixed media on game board. Photo: courtesy Hollis Taggart Galleries.

Brenna Youngblood at Tilton, closes April 19.

Youngblood tends to be a commentating artist, so she’s difficult to describe without using quasi-academic-sounding words. Her mixed media works here often make reference to domesticity, or the “domestic sphere,” what with their fan blades and wood paneling. Her bleak mixed media on canvas Still Life (2014) is so very sad-making, like looking down the wrong end of a telescope at a Chardin or De Heem: Against a vast creamy background is perched a colorful, stylized representation of a pile of fruits and vegetables. The pile could be a distant cousin of the Fruit of the Loom logo. Near the pile, a couple of patches suggest not-such-good-times ahead, or perhaps the continuation of a never-hopeful future. Still: it’s life. Maybe this is as good as it gets, 15 minutes at an Organic Avenue juice bar before looking deep into handheld screens—but never again a banquet and a leaning back of chairs, a time of such gifts and gifts of such time. Be prepared to be mildly depressed, in the manner of a sensitive cultural critic.

Elizabeth Manus

“Selected Works” at Hollis Taggart, closes April 26.

Elegant stalwarts populate the group show at this unostentatious Upper East Side blue chip gallery. There’s Richard Pousette-Dart‘s Conté crayon and ink wash on paper work, Hero and Leander, (circa late 1930s), Louise Nevelson‘s diminuitive wood collage Untitled (1965), and a 2013 untitled pink Portugal marble work by Pablo Atchugarry, sculptor of so many sensuous beauties standing throughout Uruguay. Maureen McCabe‘s box o’ balls and wheels seemed vacuumed packed with the combined spirit of Esther Williams, Rosie the Riveter, Lady Liberty, and Louise Brooks. Beginning May Day, the gallery will present 1960s works by pop artist Allan D’Arcangelo. Just know that near the gallery’s back offices, there yet might be Duchamp’s Nu descendant un escalier (1937), a small pochoir-colored collotype with French 5-centime revenue stamp, still hanging around.

Elizabeth Manus

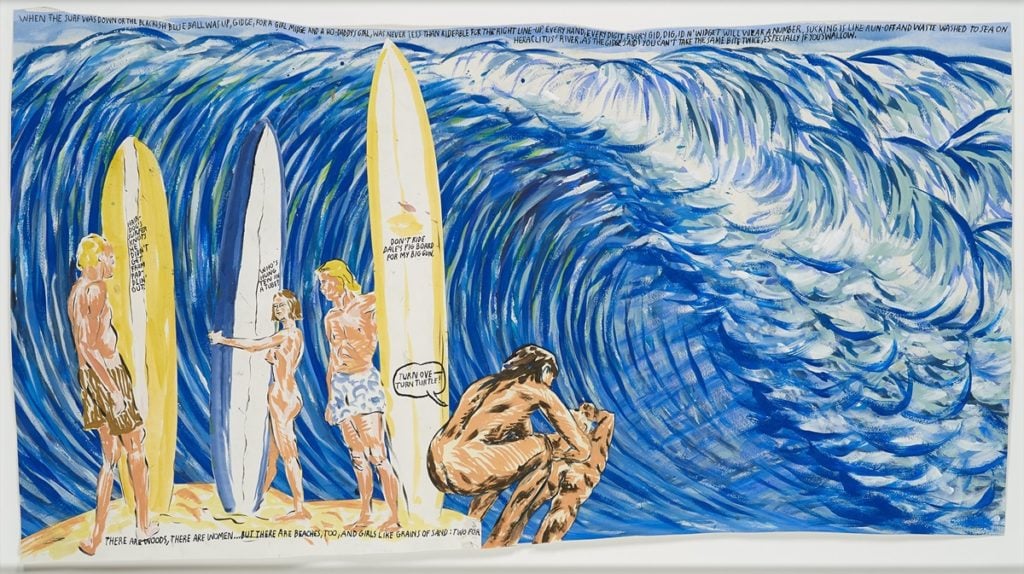

Raymond Pettibon at Venus Over Manhattan, closes May 17.

Especially if you are a Pettibon ingenue (you don’t read his Twitter feed, you have no interest in Black Flag or Sonic Youth), you may likely fall in love with him here, on the third floor of 980 Madison. Anne Bruder and Adam Lindemann scoured the US and beyond to gather Pettibon’s waterworld works. None of the ones here are for sale, alas (prepare for unrequieted coveting). The wild and weird prose smithy won me over with such texts as “Kurek had already caught some splendid gleams. / There would be no cathedral without it.”—these words written above the image of a surfer slicing through a curtain of carmine wave flaps in No Title (Kurek had already) (1987). Some of the smaller paintings and drawings, such as No Title (Here and there) (1995) are as mesmerizing as the wide-screen big-blue-wave canvases, e.g., No Title (This left was) (2012), 55 by 84 inches of pen, ink, colored pencil, acrylic, gouache, and collage on paper. My suggested Saturday afternoon itinerary for you: begin with these Pettibons, then buy some wine and sandwiches and hie thee to Central Park for a discussion of what it will take to legalize marijuana in California and New York State.

Elizabeth Manus