For most mortals, things are pretty frustrating financially nowadays, and, if you happen to live in the art world, they are even worse. We are smack in the midst of a nasty economic cycle and thick in the sticks of unprecedented social and political upheaval and violent strife. Not to mention, the U.S. is less than six months away from a historically crummy presidential election. No matter the outcome, all indicators point to the present state of humankind going from bad to yikes. I will add, though, that there is an upside to a down market: nicer, friendlier art dealers!

And then there is is Ken Griffin, master of his own monied universe, founder of Citadel, a hedge fund that has generated a record-shattering $74 billion in returns since its inception in 1990, earning him $4.1 billion in 2022 alone (also a record—of late capitalistic profiteering). Griffin’s 2023 was at least as remunerative, with 2024 slated for even higher levels of profitability on the back of massive generated so far this year.

In my biggest scoop since I revealed that Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, the impetuous, insouciant, murderous man-child ruler of Saudi Arabia had stashed his $450 million Salvator Mundi (at least a hair of which is attributed to Leonardo da Vinci) on his yacht, I can share that Griffin bought Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa’s untitled 1982 Jean-Michel Basquiat head for $200 million, almost twice the $110.5 million that Maezawa paid for it at Sotheby’s in 2017. I have reached out to associates of both parties for comment and have not heard back from either—but my sources are unassailable.

Griffin first tangoed at the top end of the Basquiat field back in 2020, during another down market (wrought by the Covid crisis), when he bought Peter Brant’s 1982 canvas, Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump, for $100 million. He sure seems to have a penchant for plump, round numbers.

The way Griffin, Maezawa, and their brethren (almost exclusively testosterone-fueled bros) burn through cartoonish sums of cash brings to mind hyperinflation in postwar Germany. Back in 1920, the German mark fell from 69 per U.S. dollar to 4,210,500,000,000 (that’s four trillion and change, if you are scratching your head) in November of 1923, when it was said that a wheelbarrow full of currency wouldn’t land you a newspaper. It’s only a matter of time before a billion-dollar Basquiat arrives.

With New York’s weakest round of spring auctions in recent memory beginning next week, look for overall results to plummet compared to previous years. There’s a dearth of major top-end material, coupled with no marquee single-owner sales.

Sotheby’s, where the proceedings this go-round seem unlikely to rise above a yawn fest, is emblematic of the state of play right now. Among its highlights is… get ready … drum roll, please… guess what? Yet another Basquiat! This time, it’s a collaboration with Warhol. Historically, these works have been viewed as an example of 1 + 1 = less than 0; the market generally frowns upon (and recoils from) gratuitous pairings, which in this instance was instigated by dealer Bruno Bischofberger in the mid-1980s. The partnership was the subject of a Broadway play a couple years ago, will be addressed in an upcoming film, and was the focus of recent blockbuster exhibitions at Bernard Arnault’s private museum in Paris and Brant’s in New York.

The painting is among the best that Warhol and Basquiat did together, and I can reveal that: a) the estimate on it was lowered since the announcement of its offering, from $18 million–$25 million to $15 million–$20 million; b) a house guarantee by Sotheby’s was rejected at $17 million; c) when the work last sold, in 2010 for $2.66 million on an estimate of $2 million to $3 million, it was consigned by Basquiat’s family; and d) the sellers are billionaire brothers Frank and Lorenzo Fertitta, of Ultimate Fighting Championship fame, which they sold in 2016. Together, the Fertittas have flipped more paintings than bodies have been flung to the UFC boxing-ring canvas.

The McLaren F1. Warning! This is not a toy—certainly not at $20 million-plus—but if you treat it like one, you’d better have good health insurance. You’ll need it! P.S., I was chased into the street by a Sotheby’s security guard for opening the door. Sorry, couldn’t resist. Photo by Kenny Schachter.

One of the coolest lots in the contemporary art sales isn’t even an artwork, but rather a McLaren F1 sports car that is being sold by under-the-radar collector Chris Cox. Past and present owners of the model are a who’s who of sports, entertainment, and business figures, such as Lewis Hamilton, Elon Musk, Rowan Atkinson, Jay Leno, George Harrison, Ralph Lauren, Nick Mason, and the Sultan of Brunei. Though Musk and Atkinson famously wrecked theirs (these are highly specialized vehicles, not for the incautious), I would gather that this rare auto will race past most of the art on offer.

Over at Christe’s, an optimistically estimated ($30 million to $50 million) but pretty 2004–07 Brice Marden painting is guaranteed by the auction house, i.e. owner Francois Pinault. A sister painting sold in 2020 at Christie’s for nearly $31 million, from famed collector Donald Marron’s estate, but I am aware that work has since been resold, with the seller taking a haircut. Given the present market environment, look for the work to become part of Pinault’s permanent collection.

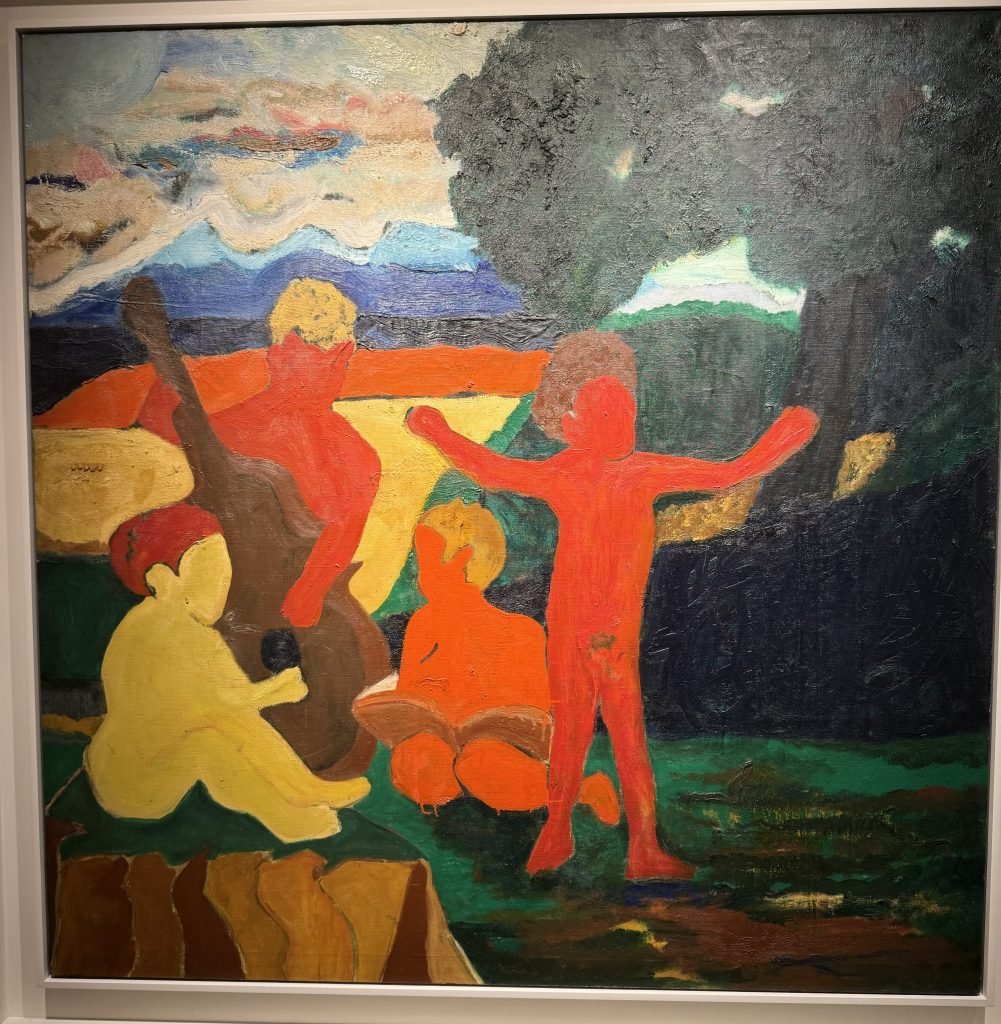

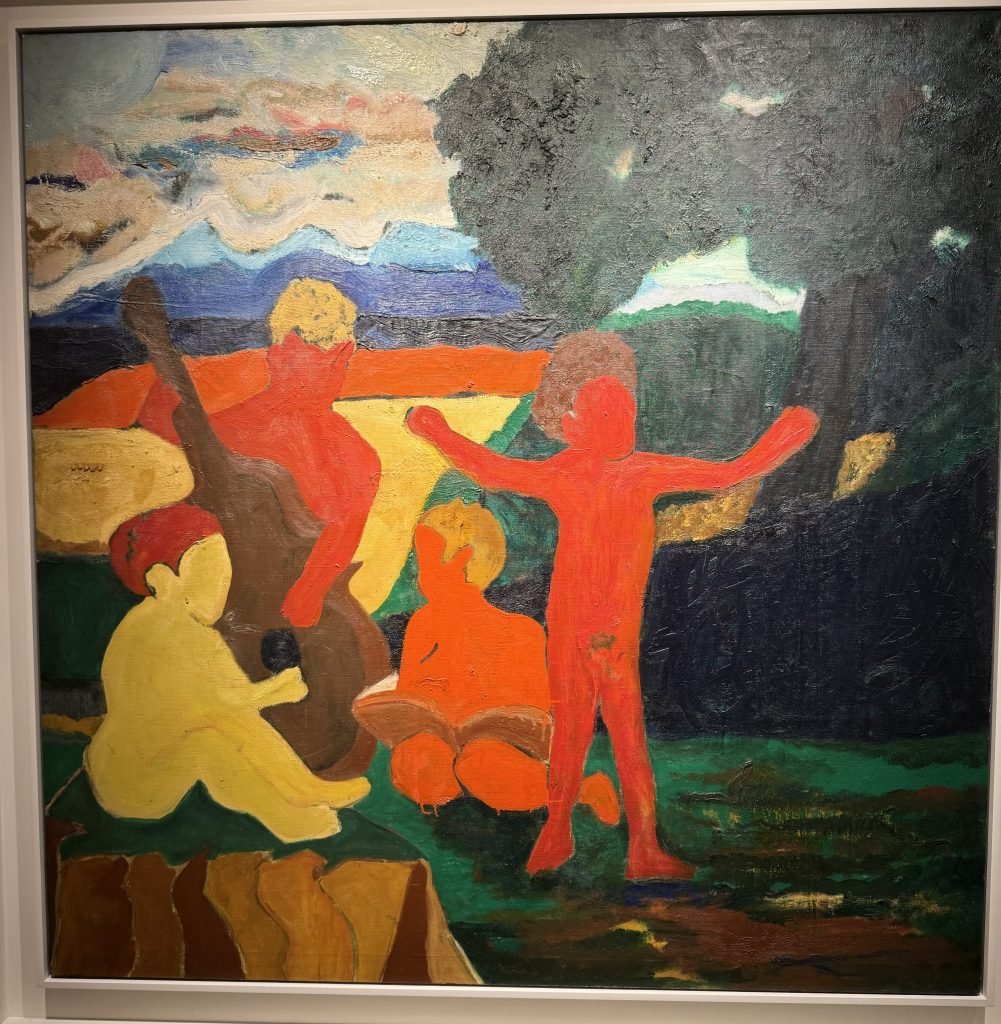

Bob Thompson’s Music Lesson (1962). Photo by Kenny Schachter.

Best of week, in my opinion anyway, is Bob Thompson’s 1962 painting Music Lesson, priced at $400,000 to $600,000 by Christie’s. I expect it to soar well above his measly auction record of $327,750, which was set at a 2013 day sale at the house.

Past the New York sales, a few words on the media circus swirling around the global Inigo Philbrick/Orlando Whitfield (who?) comeback tour and media blitz: A pair of breathy puff pieces in both Vanity Fair, by Marc Seal, and The Times of London, by Laura Pullman, were exceptional for their lack of journalistic standards and unabashed toadying.

Besides $86.7 million, Philbrick stole lines straight out of art dealer Michele Cohen’s mouth in Vanessa Engle’s BBC doc $50 Million Dollar Art Swindle, which chronicles Cohen’s stealing from dealers and collectors. Both men rationalized their dirty deeds by the fact that none of the dupes they stole from suffered a diminution in their standards of living. The seven killer sins for success as an art dealer are: dishonesty (first and foremost), cruelness, cold-bloodedness, duplicitousness, narcissism, materialism, and hypocrisy.

Best of all was Philbrick’s comedic comment in The Times: “If I wanted to hide and was trying to not get extradited, we’d have gone to Russia, we’d have gone to Iran.” The very notion of the designer-clad duo traipsing thought the streets of Tehran is almost too much to fathom. Even for me.

Whitfield wrote a book about Philbrick entitled All That Glitters that is billed by its publisher as: “A dazzling insider’s account of the contemporary art world.” Except that Philbrick always described Whitfield not as an insider but as his art handler, whom he funded (with our money, unbeknownst to me) to open a gallery for (very) inexpensive emerging art. I met Whitfield only once, fleetingly, throughout the years I was friendly with Philbrick.

Whitfield’s book, for which he was reportedly paid upwards of a $1 million advance (or thereabouts), with a TV project to follow, is an art world caricature, swathed in hyperbole and nothing more than an uninformed, downright buffoonish characterization of the social milieu surrounding the market. The Trumpian levels of histrionics involved would make the orange scourge turn a shade more crimson.

The absurd lack of perspicacity in Orlando’s undertaking was summed up succinctly by the author himself, as summarized by the Guardian: “He describes the art market as a corrupt, unregulated orbit sloshing with drugs, $5,000 bottles of wine, yachts, private jets, prostitution, and populated with oligarchs and ‘sons and daughters of the sinister rich’—all built around betting on ‘wildly unstable assets of no intrinsic value.’ ”

To begin to unpack this feeble, uninformed bunkum and balderdash (sorry for the flowery descriptive, but it’s that dumb), let’s start with the misconception the art market is unregulated. The esteemed art market journalist Georgina Adam has enumerated dozens of statutes and laws that apply to any given art transaction, from the Uniform Commercial Codes that govern commercial conduct to rules and regulations pertaining to fraud, misrepresentation, title issues, and warranties.

As far as the drugs and $5,000 bottles of wine (a detail he directly lifted from my 2020 New York Magazine feature, no doubt), in 35 years in the business, I only ever witnessed such wanton behavior in the company of Philbrick. As to the “sinister rich” and their baleful babes, there is a bell curve of morality with plenty of execrable miscreants at every level of the socioeconomic spectrum, not just the filthy rich.

Lastly, if you deny the intrinsic consequence of art, you belong anywhere but the art world. Since it came off the wall of the cave, art has been coveted and treasured throughout history. Making and appreciating it distinguishes humans as a species. Not to mention, art has calculable, medicinal values that are clinically proven. And, if you are aware of even fundamental market basics, you would know that there is absolutely nothing unstable about good art, which is incontrovertibly objective. If you know, you know.

Back to my back: I choose not to dwell any further this week on the subject of my surgery, as I’m too tired to get into it and there are plenty of people suffering inordinately more than me. Though I will add that, five weeks after needing Oxycontin 90 minutes before I could sit up in bed (much less attempt to stand), when my pelvis felt like it was being pulverized by a baseball bat, my physiotherapist said that I’ve made the most remarkable recovery she’s seen in decades. For that, I am not only lucky but eternally grateful.