When Angela Gulbenkian met a German art investor she wanted to impress, she made them an offer they couldn’t refuse: fly over to Portugal and visit the family palace in Lisbon. The Gulbenkians, of course, were a fabulously wealthy family of famous art collectors. The Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Portugal is famed worldwide for its collection of 6,000 pieces of art, ranging from Egyptian antiquities to works from the classical era, right through to 18th century French decorative arts and 20th century works by René Lalique.

One couple made the journey to Lisbon expecting a guided tour. According to a former colleague of Gulbenkian’s, the pair called the young art-world insider on arrival and were told (after their sixth time trying to reach her) that she was on a super-yacht in the ocean and wouldn’t be able to meet them. They apparently later caught sight of Gulbenkian on her phone in a Lisbon parking lot.

“Angela was all about dropping names of princes, kings, sheikhs, and so on,” said the former contact. “She was incredibly convincing, and people believed her.”

The game was up for Gulbenkian on July 28 this year, when a London court sentenced her to three-and-a-half years’ imprisonment on two counts of fraud after she pocketed $1.4 million for the sale of Yellow Pumpkin, a statue by Yayoi Kusama. Gulbenkian sold the piece to a Hong Kong dealer, but there was a problem: She didn’t actually have it to sell.

Gulbenkian would later join the roll call of art-world scammers alongside the likes of Inigo Philbrick and Anna (Delvey) Sorokin; the three recent fraudsters all allegedly failed to deliver on promises to the art market’s upper tier. (Philbrick is currently awaiting trial in a Manhattan correctional facility; Sorokin was released on parole in February.) Each one charmed the art world with claims of impeccable pedigrees, unbeatable contacts, and remarkable expertise—only to leave clients, colleagues, and friends holding the bag.

“The high-end art market makes it easy for confidence tricksters like Angela to operate,” said Chris Marinello, an investigator of art fraud, who pursued the Gulbenkian case.

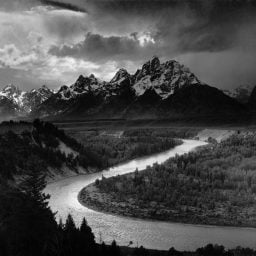

Museum Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon, Portugal. Photo by: Jeffrey Greenberg/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Myth-Making

Gulbenkian, who is German, had acquired the name by marrying Duarte Gulbenkian, the great nephew of Calouste, a man of legendary wealth in the early 1900s. (He was known as “Mr Five Per Cent,” according to a recent biography, because of the commissions he charged on the sale of Middle Eastern oil.) In the years before his death in 1955, Calouste rated as the world’s richest man, according to the book’s author, Jonathan Conlin.

Like so many fraudsters, Angela Gulbenkian, who is now 40, knew the power of appearances. Her icy blond hair was the first thing that struck those that met her, but so too did her extravagant fashion sense. When the money came in from the Hong Kong gallery to her personal account for the Kusama, she went to town, blowing the money on a Rolex watch worth $25,000, global travel, art for herself, and even a private plane rental, according to London court documents.

She was something of an influencer, too, managing to get close enough at an exhibition to the famous Chinese artist Ai Weiwei to get a photograph with him for her Instagram account. Gulbenkian was repeatedly photographed in high heels and couture-like attire. According to a source who worked with her, she frequently borrowed lavish jewelry from designers who hoped she would show it off in the high-end social circles she claimed to move in.

Nubar Sarkis Gulbenkian, son of Calouste Gulbenkian, with J. Paul Getty. The Gulbenkian’s name has long-been associated with power and money. Photo by George W. Hales/Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Gulbenkian ventured into the formal business of art with a partnership in February 2016 with Florentine Rosemeyer, an agent and author in the Munich art world. They planned to establish an online marketplace for private art sales. FAPS-Net, an abbreviation for Fine Art Private Sales Net, was intended—ironically, it seems in hindsight—to bring more transparency to the art trade.

FAPS-Net produced minimal financial results and Rosemeyer left the company in February 2018. Accounts at Companies House in London show that the partnership was in capital deficit to the tune of almost £25,000 at the time of her departure. FAPS-Net was dissolved in December 2020—neither Rosemeyer nor the company was accused of any wrongdoing. The writer contacted Rosemeyer’s lawyers in London, and she declined to comment for this piece.

Angela Gulbenkian, Mon Müllerschön, and Florentine Rosemeyer in Munich at an art show in 2016. Photocapes: Michael von Hassel Hassel via IMAGO.

A Trail of Deceit

The Hong Kong art advisor Mathieu Ticolat paid Gulbenkian $1.4 million for the Pumpkin that never arrived (including a deposit of $100,000, which Gulbenkian passed on to the seller’s agent). He put it quite simply during Gulbenkian’s sentencing in court in Southwark, U.K.: “It was all a mirage.”

Indeed, the fraudster got away with serious deceits and thefts for years, mainly by making excuse after excuse, according to a source who has knowledge of Gulbenkian’s business dealings. She was arrested in Lisbon in June 2020.

James Ashcroft was a London dealer who came to rue the day he met Gulbenkian in 2019. She sold him, through an agent, a picture of Queen Elizabeth the Second by Andy Warhol for £120,000. Ashcroft was forced to return the picture to the seller after being told that he did not have legal title.

Gulbenkian had taken advantage of a relatively common art-market practice, the use of intermediaries, which can prevent both sides of a transaction from knowing the ultimate client’s identity. “He [the owner] gave the picture to Angela, but Angela never paid him, she kept the money,” Ashcroft said in an interview. “She stole the picture.”

Art-world insiders were not Gulbenkian’s only target. Another victim was Percy Bass, an interior design shop in Knightsbridge, U.K., that was commissioned to create some wallpaper based on the Kusama pumpkin motif for Gulbenkian’s flat in Battersea. Its production cost £5,000 and, when the company started to chase the debt, the shop’s owner Jane Morris said that Gulbenkian told them the money would be paid by the Gulbenkian Foundation accountant—but that they would have to wait, as he was away on holiday. She even made up a name for the accountant—Macario Castro—and a fake email address.

“I ended up ringing the Gulbenkian Foundation asking to speak to the accountant, but they’d never heard of him,” Morris said. “It was all made up.” The shop eventually had to write off £7,000, which had accumulated interest. “She was so confident and bold,” Morris said. “She strode through my shop with such arrogance.”

The experience prompted Morris to look further into Gulbenkian’s accounts. She found that her shop had previously fitted a carpet for Gulbenkian’s Chelsea flat. At the time, the client had complained about the state of it and wanted it replaced, but when Morris sent a carpet fitter to look into the matter, he found Gulbenkian’s little white dog had scuffed it.

Gulbenkian also targeted her trainer and masseuse in London, deceiving her into believing Gulbenkian could double her money by investing it in art. Jacqui Ball handed over her life savings—£50,000—to Gulbenkian, who made up a litany of excuses to save having to return it. Some three years after the transfer, she paid it back without interest, according to statements made at the hearing.

Screen prints of Queen Elizabeth II by Andy Warhol, similar to the work Gulbenkian was accused of illegally selling. Photo by Ian Gavan/Getty Images)

Steal of a Deal

Gulbenkian was an outsider in the sophisticated Munich cultural circle. Her family had created a successful optician business in the suburbs of Munich, but it had no connection to the art world. The author contacted Angela and Duarte Gulbenkian directly, Angela Gulbenkian’s lawyers in Munich, and Angela Gulbenkian’s mother’s lawyer in Munich.

When she married into the Gulbenkian family in 2010, she saw the value of Duarte’s family name and started to circulate around the Munich art world. As we have seen, the Gulbenkian name elicited great interest among the artistic community and Angela exploited this by, among other things, offering visits to the Gulbenkian palace in Lisbon, which she could not actually provide.

She was a quick learner, said one German art expert. “Angela was extremely charming, charismatic and was very good at hinting and not denying her connection with the Gulbenkians, from Portugal,” they said.

Back home, there was little surprise about her eventual fate. Gulbenkian had, according to a former business associate, failed to pay a colleague the proceeds of the sale of a picture she had sold at an exhibition. Gulbenkian allegedly sent the colleague a deceptive bank statement; the colleague was incensed that Gulbenkian had not paid the exhibition organizers. They said it took months of fighting to get the repayment, and the pair later fell out.

Scams like Gulbenkian’s are symptomatic of a broader problem in the art market: it is too focused on who one knows, rather than what one knows, according to Marinello, the investigator who pursued her case.

“They had said that they would get you a sculpture that they did not even own,” he said. “Fraudsters like Gulbenkian have destroyed the art world… [It] used to like dealing that way, with a handshake, but people like Gulbenkian have given all art dealers a bad name.”

Ticolat, the French art advisor based in Hong Kong who lost more than a million to Gulbenkian, still feels bitter. “You are very ashamed when you get scammed,” he said. But even he says it is hard to deny the influence she wielded in the art world—if only for a short while.

“I trusted her, I trusted her name,” Ticolat said. “Everyone has heard of Gulbenkian.”