A version of this story first appeared in the spring 2020 Artnet Intelligence Report.

It was late 2018 and Karen Boyer, a Miami-based art advisor, was over the moon.

She had just received an email from a young London-based art dealer by the name of Inigo Philbrick announcing that he would launch a second location of his eponymous gallery in a somewhat unlikely place: Miami’s Design District.

“There are almost no blue-chip galleries in Miami, and he was a very prominent, seemingly successful secondary-market dealer,” Boyer said. Having run into Philbrick over the years at VIP openings and spotted him comfortably bidding on seven-figure works at auction, “I thought this was a big plus for Miami.” Philbrick told her via text that he had signed a seven-year lease.

Less than a year later, both his Miami and London spaces have closed. Packages sent to the galleries return unopened. And Philbrick himself—once an omnipresent figure at art-market events, usually sporting a five o’clock shadow, a tailored Italian suit, and a shirt with the top two buttons unbuttoned—has vanished.

In his wake, he has left a growing pile of lawsuits claiming he sold the same works to multiple clients and defaulted on loans he secured using art he didn’t own as collateral. Now, disgruntled former business associates are trying to seize his personal assets, which filings suggest could amount to as much as $70 million, as well as $150 million from his business.

How was a young dealer able to deceive some of the most sophisticated collectors in the world—beginning when he was just a few years out of university? And what does his precipitous rise and even more dramatic fall tell us about the state of the art market?

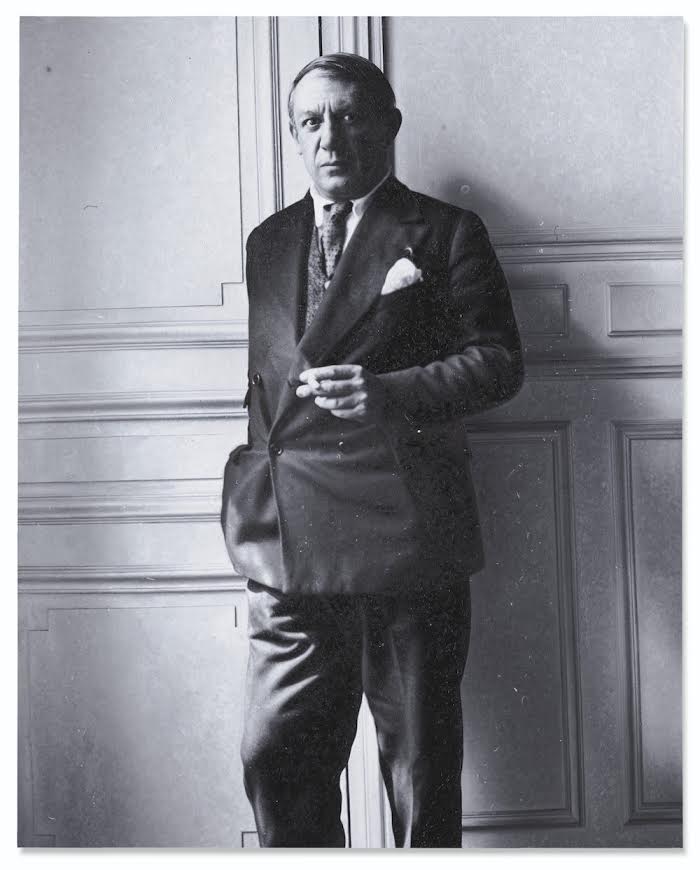

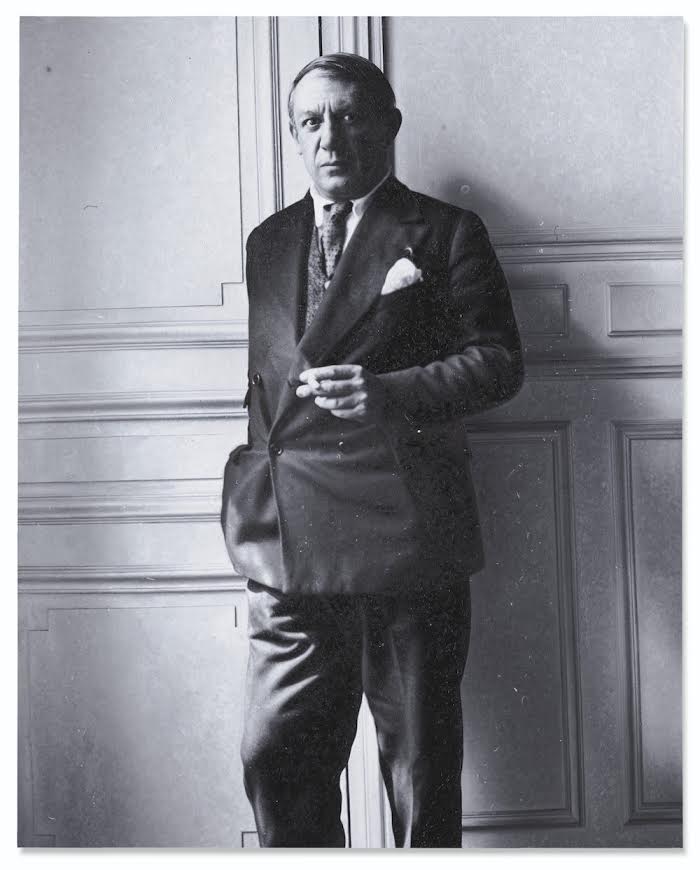

Inigo Philbrick allegedly scammed high-flying art collectors around the world. Photo collage: Artnet Intelligence Report.

The story of Inigo Philbrick is the story of a man who, depending on whom you talk to, is either a well-intentioned and ambitious dealmaker who got in or over his head or a vain grifter who preyed on investors gullible enough to hand over money and art.

Regardless of which Inigo Philbrick you pick, one thing is clear: he was able to operate because the art market, for a long time, supported him—and because his aggressive tactics, before they got out of control, were celebrated and even envied by the very people he exploited.

Interviews with Philbrick’s clients and associates, a thorough examination of the lawsuits against him, and a review of his company’s own records reveal that Philbrick is very much the product of a system that thrives on opacity—one that is full of profiteers making deals through offshore shell companies, buying art for no other reason than to flip it for a profit, and relying on a paucity of regulation to operate unchecked.

Only in this sort of system could a player like Philbrick—a middleman who had no relationships with artists and few with actual collectors who buy art to hang in their homes—get as far as he did.

Friends in High Places

Among those stunned by Philbrick’s downfall is his former boss, Jay Jopling, the founder of London’s prestigious White Cube gallery. Philbrick started there as an intern in 2010 at just 23 years old and quickly rose in the ranks to lead Jopling’s secondary-market business.

“He struck me as a smart, ambitious young man with a good eye for art and an impressive commercial sense,” Jopling said in an email. When Philbrick “decided to launch his independent career in 2013,” Jopling continued, “I agreed to support him financially.”

The pair continued to do business until Philbrick’s house of cards began tumbling down last year—and now Jopling is one of numerous players jostling to be among the first in line to get his money back. After the first major lawsuit was filed against the young art dealer, in early October, Jopling was granted an injunction in London’s High Court to protect his business interests with Philbrick. Over the past five months, three additional offshore entities and shell companies have filed similar claims.

Jay Jopling, owner of White Cube. Photo by Oli Scarff/Getty Images.

It appears Jopling worked with Philbrick through a mysterious offshore entity called Ogini Ltd, which was incorporated in Jersey in the Channel Islands in 2017. Although Jopling declined to comment on whether he owns the entity, the address for Ogini is identical to a White Cube entity also registered in Jersey, and Jopling previously disclosed that the court granted his injunction request on November 1, 2019—the same date as an injunction granted to Ogini. A source familiar with the filing says it contains exceptionally detailed information on Philbrick’s activities, suggesting a close relationship between the entity and the dealer.

Another clue? Ogini is Inigo spelled backwards.

A Business Built on Secrets

Some say the Philbrick affair will be a wakeup call for an art market that has become increasingly financialized but is still not subject to the same level of regulation as most financial markets. Philbrick, for example, often provided his profit-hungry financial backers with verbal or written assurances about the whereabouts or title of a particular artwork—but rarely provided supporting evidence.

“Outside of any potential government intervention or legislation, it’s a call to begin to operate in a slightly more CYA [cover your ass] manner, in which we establish ways to sort out what true title is amongst ourselves, and to be less lackadaisical,” said art advisor Benjamin Godsill. “It’s a great spurning of self-regulation based on self-interest.”

In fact, it’s something of a miracle that fraud doesn’t occur more often. Even in the most routine art transactions, buyers and sellers typically have no idea who is on the opposite end of a deal, not to mention any clue about how many operators—advisors, dealers, financial backers—might get involved along the way. The frequent use of offshore shell companies to conceal investors’ true identities only obscures matters further.

Philbrick, evidently, was a past master at turning the art market’s blind spots into lucrative loopholes, taking advantage of the plethora of sophisticated financial strategies that cropped up as the global art market ballooned over the past two decades, including third-party guarantees, less formal “flipping” agreements, and art-backed loans. For an older generation of traditional collectors and connoisseurs, such convoluted deals might be anathema, but for a younger generation of risk-tolerant buyers, they have become the norm. Art collecting, it seems, has been replaced by arbitrage.

In all his dealings, Philbrick adopted a common MO: sharing a measure of risk with clients to buy and sell a work of art without ever taking physical possession of it, and sharing in the upside when the flip made a profit. For a while, it worked swimmingly. The strong returns Philbrick secured early on may have prompted some backers to look the other way as red flags began to mount and other market players began to avoid doing business with him.

Inigo Philbrick ©Patrick McMullan. Photo by Liam McMullan / PMC.

What made Philbrick exceptional was not his tactics but rather the margins he was promising, the number of backers he was working with, and the number of deals he had in the works at any given time. “He’s kind of a secondary-market assassin—pure speculation,” said one dealer. “He attached himself to certain markets that were perceived as blue-chip and rising, with exponential profits.”

But before long, some of those markets began to falter, and Philbrick found himself furiously moving funds around from one client and deal to the next in order to stay afloat. According to a detailed report he filed with Companies House, the UK business registry, in August 2018, Philbrick’s turnover in the 2015–16 financial year was £50.6 million, with a relatively slim profit of £1.6 million. Turnover nearly doubled, to £96.4 million, the following year—but Philbrick still posted a loss of £935,000, which he attributed to “currency loss” from a devalued pound sterling.

“It might have been fake all along,” said one advisor. “He might have been stealing from Peter to pay Paul. Certainly, there are Pauls out there who made out like bandits.”

An Auspicious Start

Given Philbrick’s comfort with treating artworks as less-than-glorified financial derivatives, it is somewhat surprising that he is the son of a fairly eminent museum director. His father, Harry Philbrick, was the director, from 1996 to 2010, of the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut, where he staged ambitious shows by difficult artists like Anselm Kiefer. Afterwards, he spent five years running the museum at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, where he, too, engaged in a kind of art flipping: he deaccessioned Edward Hopper’s East Wind Over Weehawken (1934), selling it at Christie’s for $40.5 million (double its low estimate), in order to buy the museum more contemporary art.

Growing up in Connecticut, Inigo graduated from Joel Barlow, a highly ranked public high school in Redding, in 2005 after a stint or two on the school’s honor roll. Like his father, he attended Goldsmiths at the University of London. Their relationship became strained, however, after Harry divorced Inigo’s mother in 2006 and remarried in 2009, according to ARTnews.

In an email, Harry Philbrick said that “while Inigo and I have been estranged for nearly a decade now, I love him and want the best for him.” He described the allegations against his son as “deeply concerning,” although he said he has “no knowledge of what transpired beyond what has been publicly reported.”

Philbrick did not broadcast the estrangement with his father, consistently presenting himself as more confident, more informed, and more connected than anyone else in his orbit. “When you Googled the name, you came across his dad,” one dealer recalled. “No one knew they were estranged.” Six years before Philbrick got his job at White Cube, he was already leveraging his art-world ties, bringing his friends—including now-film director Gia Coppola— to visit the celebrated artist Rirkrit Tiravanija’s Land Foundation on a trip to Thailand.

In the years after he left White Cube, his decision to strike out on his own seemed by all accounts a wise one. He was often spotted front and center at major evening auctions—an eyebrow-raising position for someone so young—sitting alongside Artnet News columnist Kenny Schachter. Schachter has since written about his falling out with the dealer, which he said pushed him to sell off part of his collection at Sotheby’s to offset his financial losses.

A now-deleted Instagram photo of Victoria Baker Harber with Inigo Philbrick. Photo courtesy: Wikinetworth.com

Several people who knew Philbrick described his laser-like focus on deal making and the intricacies of a particular artist’s market, as opposed to the art itself. “He came across as quite quiet and really kind of facts-based, meaning all about the deal,” one person said. “I never heard him talk about art so loquaciously” as he did about finances. Others said he had an encyclopedic knowledge of the catalogues raisonnés of the artists he speculated in.

According to the Baer Faxt, a subscription-based art-market newsletter that tracks major buyers at auction, Philbrick bid on at least 11 six- and seven-figure works between 2014 and 2018 and won four of them. The priciest acquisition he made during this period was a $3.5 million Jean-Michel Basquiat, followed by a $3.2 million Christopher Wool.

Philbrick’s extravagant spending extended beyond business to his lavish lifestyle, complete with private planes and bottle service at nightclubs. His girlfriend at the time of his disappearance, Victoria Baker Harber, is an English socialite best known for her role on the popular British reality show “Made in Chelsea.” She moved to Miami when Philbrick opened his gallery and launched her own boutique, called the Space.

In an Instagram message, Baker Harber told us she “was running the store separate from” Philbrick and declined to comment on his legal troubles. “Wish I could be of more help,” she wrote, “but am in the dark!”

A Dream Deal

Firmly ensconced in the international art market, Philbrick struck what appeared to be a dream deal in 2015. It would ultimately be his undoing.

He signed on to buy and sell blue-chip works at a profit on behalf of a two-person company called Fine Art Partners (FAP), founded by former Morgan Stanley banker Daniel Tümpel and Loretta Würtenberger, a German judge turned art researcher.

Under the terms of the agreement, they would jointly acquire works—at a very favorable split for Philbrick, who only had to provide 30 or 35 percent of the purchase price. Philbrick would hold the works in storage until it became clear they were likely to reach a predetermined target price, at which point he would flip them. Notably, FAP did not require Philbrick to pay his share of the purchase price until the resale was complete, giving him ample time and cash to operate.

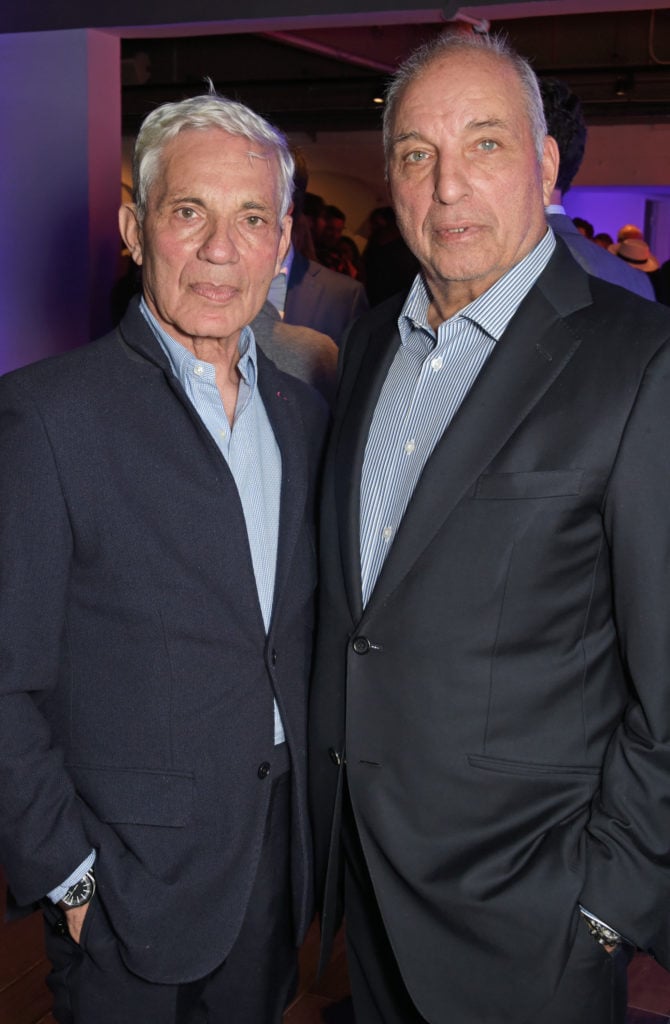

Loretta Würtenberger and Daniel Tümpel. ©Rolf Zscharnack

Each artwork had its own contract specifying the acquisition price and the target sale price. An untitled Donald Judd stainless-steel sculpture purchased for $2.25 million in 2015, for example, had a target resale price of $2.8 million, while a photorealist portrait of Pablo Picasso by Rudolf Stingel, bought for $7.1 million, had a target of $9 million. The division of profits hinged on whether Philbrick was able to sell the work for more or less than the target price; a discount would eat into his cut.

The agreement was initially lucrative for both sides. But Tümpel grew increasingly frustrated as months passed with no resales. He wrote repeatedly to Philbrick stressing the need for FAP to have money in order to pay its tax bills. Philbrick’s lengthy and elaborate responses now look like a master class in stalling. “To rush these sales is signing your own death knell,” he wrote, somewhat incongruously, at one point.

A Deal Gone Wrong

As things deteriorated, it became clear that the amount of latitude FAP had given Philbrick—and the limited amount of information he was sharing—were creating problems.

Correspondence between FAP and Philbrick contains numerous references to a buyer named Leonid, whom several sources identified as Leonid Friedland, cofounder of Mercury Group, which owns Phillips auction house. According to emails attached to the FAP lawsuit, Friedland bought an untitled Rudolf Stingel painting of two ravens from Philbrick and FAP for $6 million in 2017.

The same work sold at Phillips in 2018, with a third-party guarantee, for the slightly lower price of $5.9 million. A year after that, Philbrick and Tümpel were still discussing the fact that Friedland had not paid the $6 million he owed for the work, even as Philbrick inexplicably proposed selling yet another Stingel triptych to Friedland for $5 million.

“A deal is a good deal when it is completed and you’ve got profit in your pocket,” Tümpel wrote to Philbrick. “I believe the Raven should have been paid out by Leonid by last autumn…. That that has not happened yet, is frustrating for me and maybe this is due to the German vs. the Russian perception of doing business.”

Rudolf Stingel, Untitled (2012). Image courtesy Christie’s.

The transaction raises many questions. If Friedland acquired the work in 2017 for $6 million, why had he not paid for it by March 2019? Even if it was Friedland who consigned the work to Philllips (which seems likely), the painting carried a third-party guarantee, which means that the auction house had a committed buyer lined up.

Why, almost two years after the initial sale and after the painting had changed hands yet again, would Philbrick and FAP still be discussing Friedland’s nonpayment and not that of the third-party guarantor? And if Philbrick did receive the money from Friedland without notifying FAP, where did it go? Through Phillips, Mercury Group declined to comment. Neither FAP nor its attorneys have responded to numerous requests for comment.

Even as FAP continued to pursue Philbrick for money and information about the status of resales into early 2019, the young dealer was, according to its lawsuit, illicitly selling work out from under them.

In perhaps the most extreme example to surface to date, legal documents show that Philbrick sold multiple overlapping shares in the Stingel painting of Picasso. Two months before he told FAP in March 2017 that they had acquired the work in full for $7.1 million, he had already invoiced Satfinance, a firm controlled by the young collector Sasha Pesko, for a 50 percent share of the same painting worth $3.35 million.

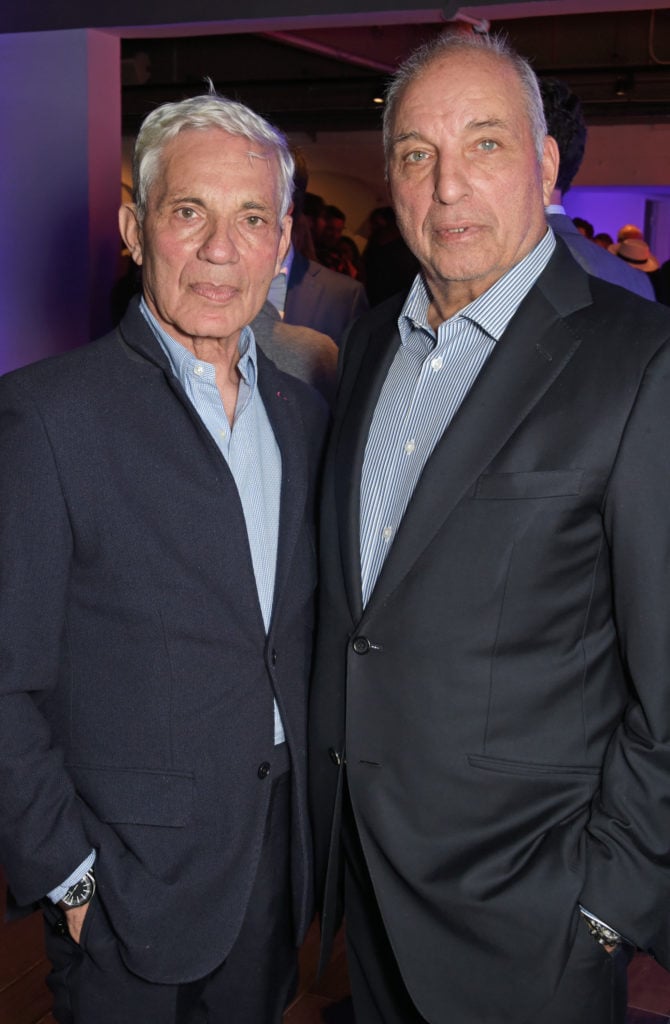

Simon and David Reuben. (Photo by David M. Benett/Getty Images for Lyric Hammersmith)

Documents show that later, in June 2017, Philbrick sold the painting again—this time to Guzzini Properties, an investment vehicle controlled by billionaire UK brothers Simon and David Reuben. Title was transferred to the brothers, who, around two years later, consigned the painting to Christie’s, where it sold for $6.52 million.

All the while, Philbrick kept FAP under the impression that the work had been consigned on its behalf and that he had secured a guarantee from Christie’s for $9 million—conveniently, the work’s target sale price—by falsifying documents, including an eight-page seller’s agreement that bears Christie’s Rockefeller Center address at the top.

Now, FAP, Pesko, and the Reuben brothers are fighting in court, each claiming to be the rightful owner of the painting. While the lawsuits are ongoing, a judge has ordered Christie’s, which is not a party to any of the litigation, to keep the painting in storage.

The Beginning of the End

FAP sued Philbrick on October 4, opening the floodgates. Since then, at least five other legal claims have been filed in US courts for numerous works, including the Stingel of Picasso, a Yayoi Kusama “Infinity” room, and a Basquiat painting of two crowned figures titled Humidity (1982). London’s High Court has also granted at least four separate requests to freeze Philbrick’s assets.

Further complicating matters, Philbrick used the Basquiat, as well as four other works, as collateral for a $10 million loan, which he later increased to $13.5 million, from specialist lender Athena Art Finance. Philbrick was declared in default in October, when he missed a six-figure interest payment, and Athena secured the Basquiat as it was on its way back from a show at the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo. Pesko, the young collector who also bought a share of the Stingel, says he is the Basquiat’s rightful owner, having paid what he claims was an inflated price for a 66 percent share in 2016.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Humidity (1982). Photo: Phillips de Pury.

“This fraud was as sophisticated as it was brazen, and time will tell whether Philbrick acted alone, or whether others should be held accountable for the damage he has left in his wake,” Pesko’s attorney Judd Grossman said. “The problems that can arise due to the lack of transparency in the art world are magnified in cases like this, where bad actors look to find a way to pledge the same art, to multiple players, ostensibly for different purposes.”

Sources say there are likely dozens more people who have been swindled, and many additional works that will be subject to claims in the wake of Philbrick’s disappearance. Messages sent to Philbrick at his gallery’s former email address bounced back as undeliverable. For now, his whereabouts remain unknown, though rumors have put him everywhere from the Bahamas to Australia to the Solomon Islands. Philbrick’s Miami attorney stopped representing him in December, noting that the dealer had “failed to fulfill his obligations.”

Asked if she thinks the art world will become more cautious, or demand more transparency, in the wake of the Philbrick scandal, Miami advisor Karen Boyer was unfazed. This drama, she suggested, only affects the segment of the art market that treats art as nothing more than a financial instrument. “When I assist clients in acquiring artwork, we pay for it and take possession of the art,” she said. “I work with a small percentage of people that I know and trust. I don’t ever buy 50 percent of an artwork.”

A version of this story first appeared in the spring 2020 Artnet Intelligence Report. To download the full report, which has juicy details on how A.I. could transform the art industry, what art top collectors are buying (and why), and how titans of the finance industry are infiltrating the auction houses, click here.