The Art Detective is a weekly column by Katya Kazakina for Artnet News Pro that lifts the curtain on what’s really going on in the art market.

Reflecting on the contemporary art market’s voracious appetite for portraiture today, an art dealer recently told me over coffee: Imagine all these collectors waking up one morning, looking around their homes, and asking themselves, “Who are all these people?”

It was a joke, of course. But it got me thinking: Is there figuration fatigue on the horizon?

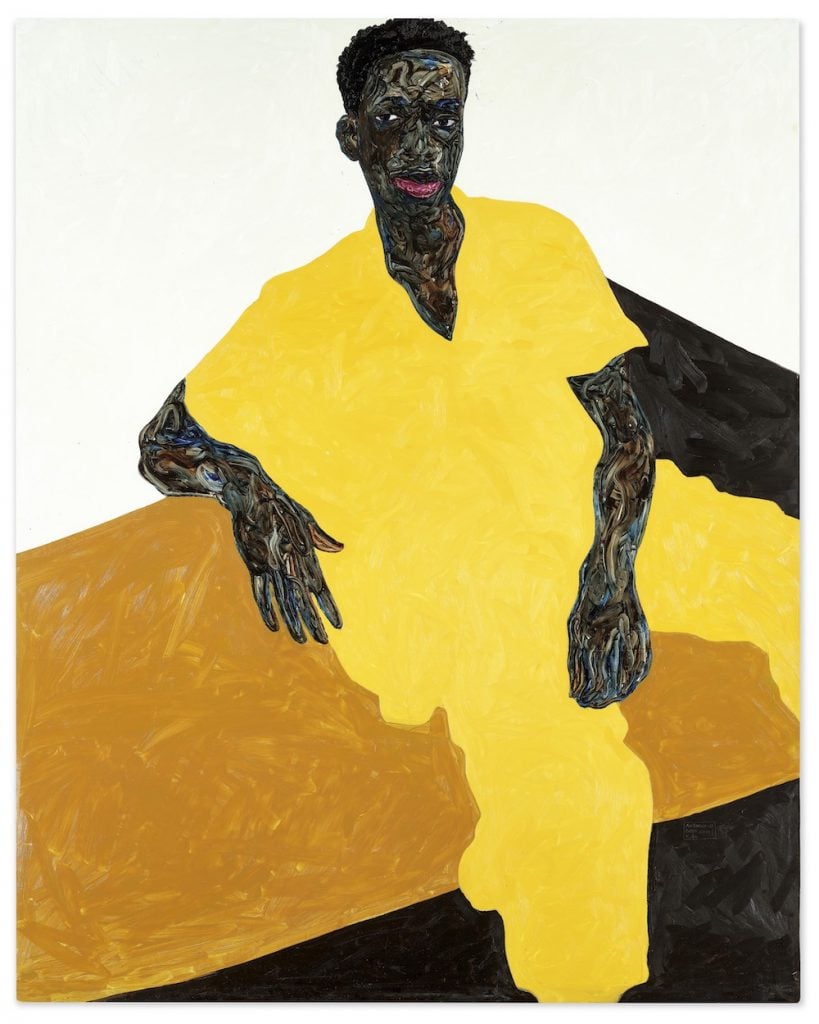

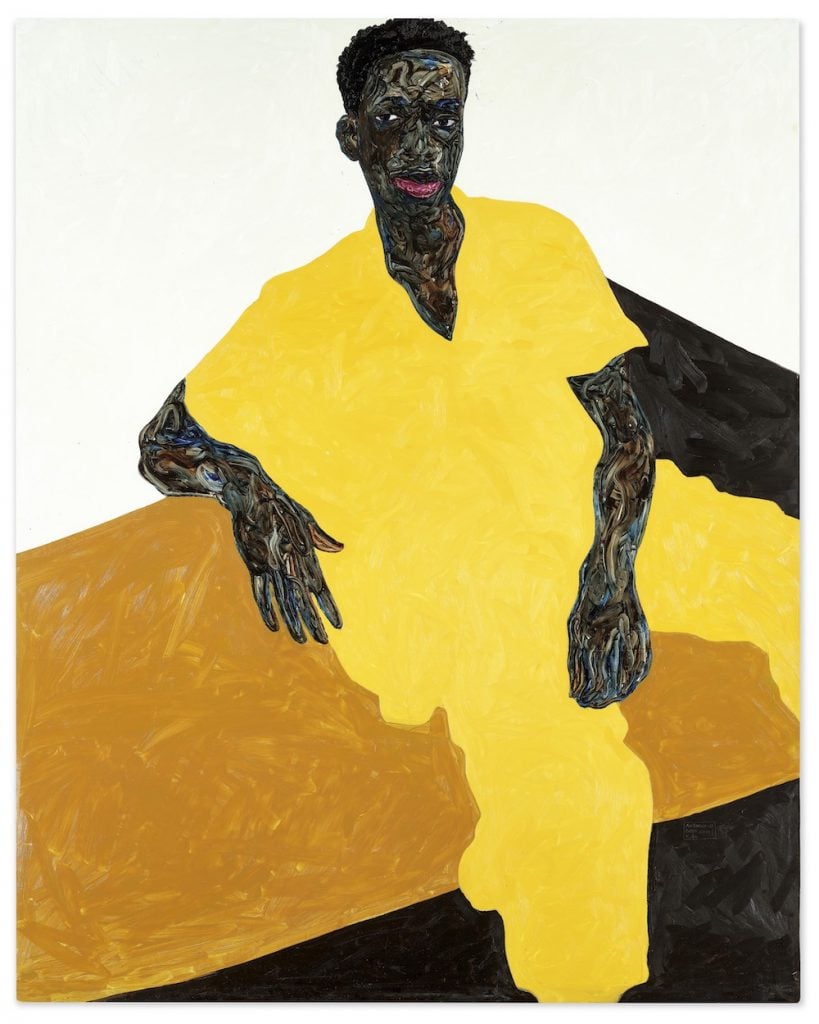

There’s a glut of figurative art out there: on social media, in galleries, auction salesrooms, and museums. Building up prior to the pandemic, the desire for figurative paintings, and portraiture in particular, has only accelerated over the past 16 months. Recently, Asian collectors have been driving up prices for works by Dana Schutz and Amy Sherald, Amoako Boafo and Emily Mae-Smith.

Amoako Boafo, Baba Diop (2019). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Human figures appeared in all but three of the top 30 contemporary and ultra-contemporary artworks sold at auction in the first half of 2021, according to Artnet Analytics (two of the three exceptions depict plants and trees).

“It’s hard to get away from portraiture,” said Miami-based collector Mera Rubell, whose family museum will display new figurative works by three artists in December. “It remains powerful. Every generation has its own version.”

Artists have been depicting the human figure for millennia, starting with cave paintings. But the current obsession has been fueled by a number of factors. Key among them: As museums and private collectors alike work to fill gaps in their holdings by women and artists of color, and particularly Black artists, whose work has been undervalued for decades, portraiture has emerged as an important genre.

Some, however, wonder if the single-minded focus of profit-motivated collectors may keep them from engaging with the true breadth of cultural production. “People want to check these boxes and say they participate in the moment,” said art consultant Rachael Barrett. “They want something recognizable, something people can easily spot on a wall. I think there’s going to be fatigue of that. I do hope that the range of artistic practice of the artists of color becomes more appreciated.”

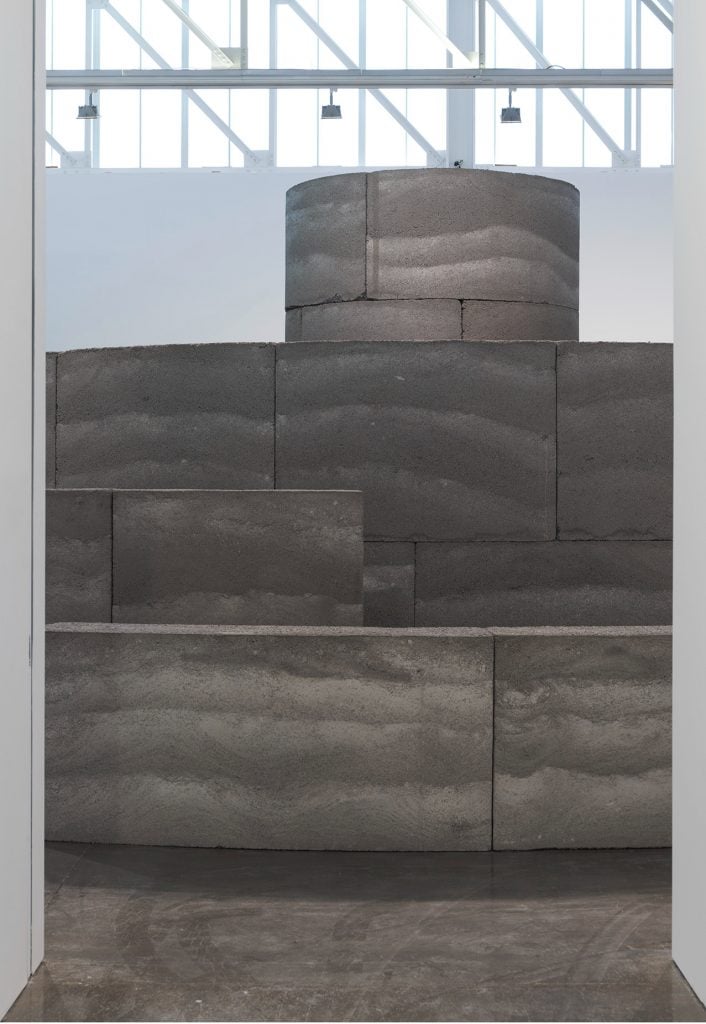

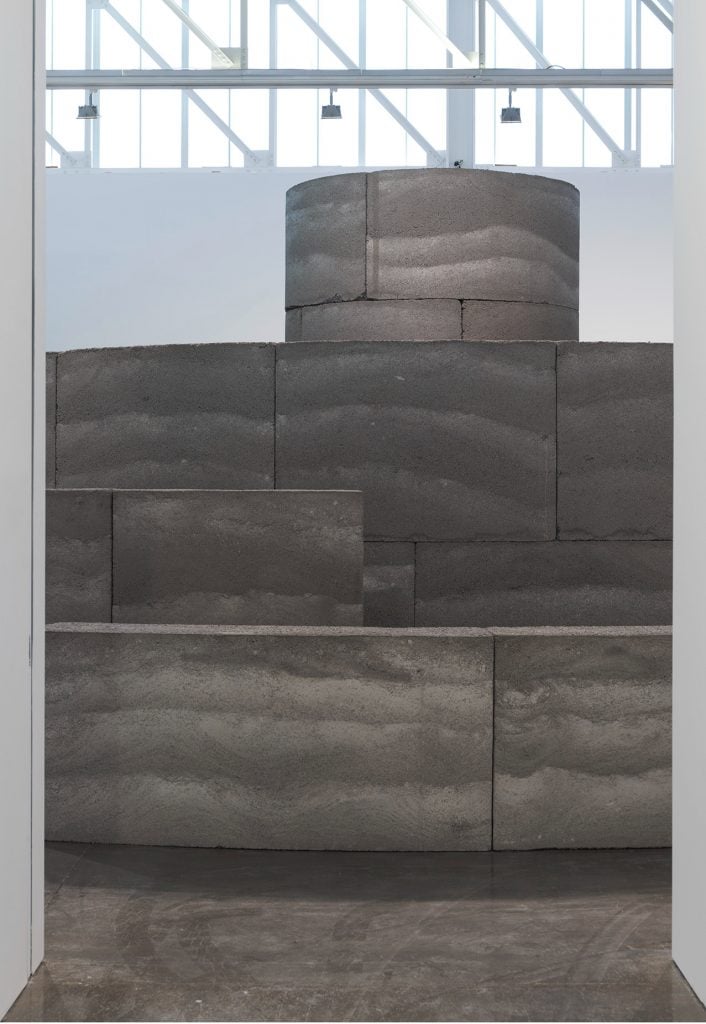

Installation view, “Hugh Hayden: Huey” © Hugh Hayden. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

There are signs this is already starting to happen. At Lisson gallery in Chelsea, Hugh Hayden has created three chapel-like spaces filled with meticulously sculpted, sawed, and woven objects such as reclaimed church pews, basketball hoops, and school desks.

Nearby, Gagosian mounted “Social Works,” an exhibition that focuses on community engagement in Black art practice, with monumental sculpture, video installations, and even a functional farm. Theaster Gates contributed a display of 5,000 records amassed by DJ Frankie Knuckles, who was influential in Black queer circles in the 1980s. House music fills the gallery and a DJ on site is busy digitizing the archive for the duration of the show.

Works of this scale and complexity would be hard to appreciate, or even grasp, on Instagram, the social media platform that contributed to the saturation of figurative art during the pandemic. Portraits are much easier to digest and acquire because people know what they were looking at.

Social Works, installation view, 2021. Artworks © artists. Photo: Rob McKeever. Courtesy Gagosian.

“Even sculptures, in lockdown, it’s hard for people to take this leap of faith and buy something digitally,” said art advisor Ed Tang. “Unless you are standing in front of it, looking at it from various angles, it’s difficult to commit to it.”

In a moment of social isolation, figurative imagery was comforting. “There was a desire to see ourselves in some way or another, to see the context around the human figure, socially, historically, or just on a physical level,” said gallery owner Franklin Parrasch. “The drive for figuration is part of the replacement of the socialization process.”

As physical interactions with art resume at museums, art fairs, and biennials, audiences may swing toward something more challenging.

“The way people are looking at art will change,” Tang said. “Can you imagine going to Venice and seeing figurative painting in every pavilion?”

While it’s hard to say what the next big trend will be, the pendulum seems to regularly swing between abstraction and figuration. And while some artists make work that responds to prevailing ideas and taste, many do what they do independently of them. Sometimes, it takes decades to understand the significance of a particular work or artist. A recent rehang of New York’s Museum of Modern Art radically paired Faith Ringgold’s 1967 American People Series #20: Die with Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon.

“We didn’t have the same versatility of context in the ‘60s when this work was being made,” said art advisor Allan Schwartzman. “Figuration was seen as dated.”

Installation view, “A Thought Sublime.” Courtesy of Marianne Boesky Gallery.

While pure abstraction remains somewhat out of fashion these days, the landscape, which hasn’t been a hot genre in decades, is making an appearance in several shows, including “A Thought Sublime” at Marianne Boesky and “Ridiculous Sublime,” organized by advisor Lisa Schiff.

“It’s something of a relief from all this figuration,” said art advisor Wendy Cromwell. “It may be a bridge back to abstraction for some artists and collectors.”

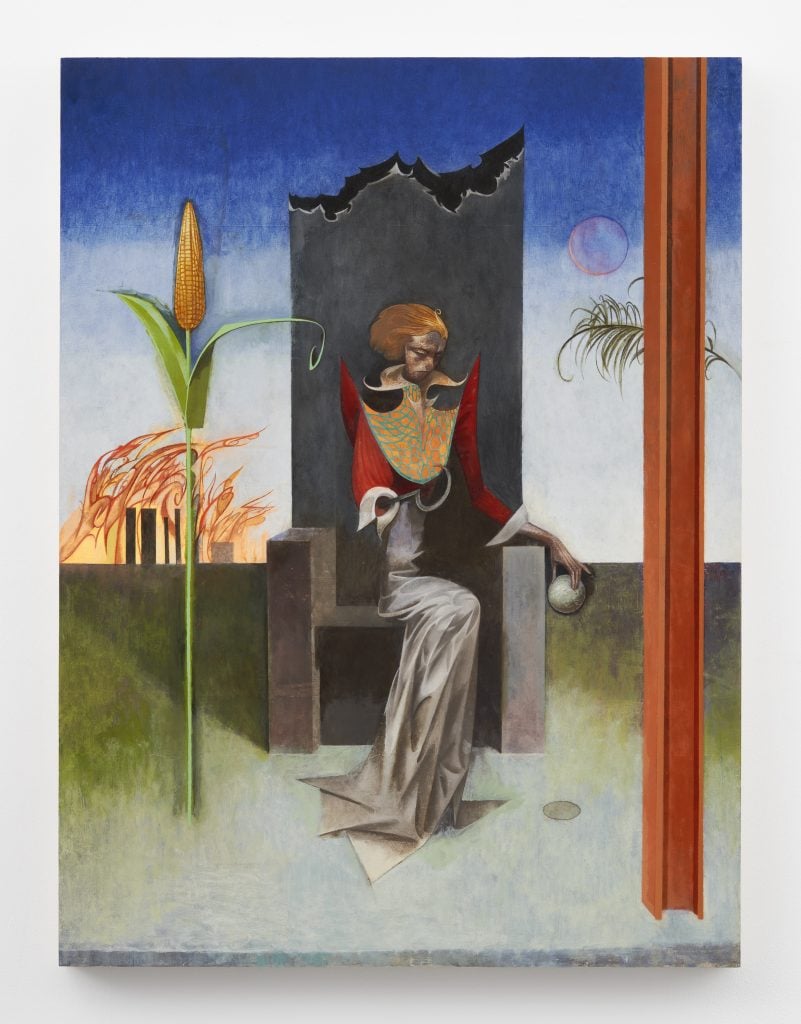

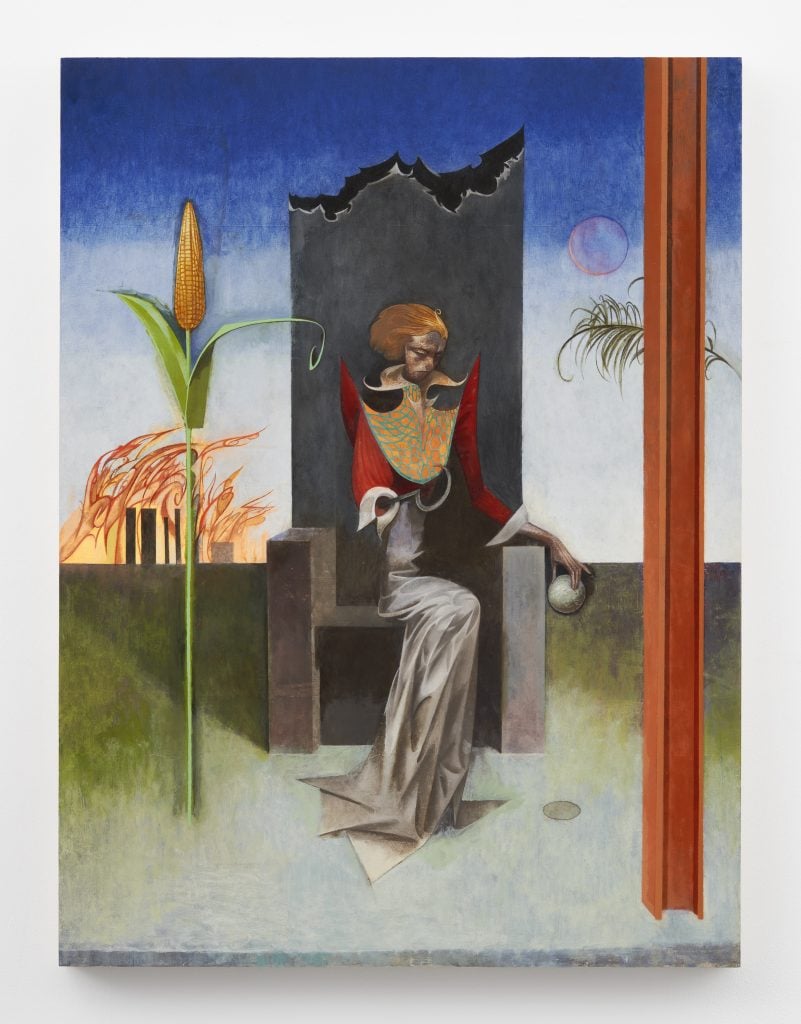

Some artists are fusing the figure and the landscape. Matthew Marks gallery sold out its current show by 31-year-old Julien Nguyen, who makes haunting portraits and jewel-like allegorical scenes inspired by the Bible, Renaissance painting, and anime. (The waiting list for his work is growing.) Prices ranged from $30,000 to $50,000.

A block north, at Cheim and Read gallery, the late Matthew Wong’s ink drawings depict his signature lone figures in exquisitely rendered mystical spaces. Several sold, with prices ranging from $275,000 to $450,000.

Julien Nguyen, Ave Maria (2019). © Julien Nguyen, courtesy of Matthew Marks Gallery.

Many see figuration fatigue as linked to the pure volume of material, some of which is bound to be of lower quality. “Bad figurative painting is everywhere,” critic Dean Kissick wrote last year in an essay on a wave of painting he called Zombie Figuration. “It crawls into every room, from museums to galleries, to cool young project spaces, to the world at large.”

Others simply long for a more sophisticated and critical level of discourse than a social media post that says: “Hey I just got this artwork. I bought it online. What do you think?”

“And there are 400 likes or kisses,” Parrasch said. “It’s never anything deep enough to create an argument. What we have is clicks and underdeveloped thoughts.”

But weaning off the figure will not happen overnight, said Ron Segev, the co-founder of Thierry Goldberg gallery on the Lower East Side.

“Collectors who are coming to me want figurative work,” he said. “I can’t convince people to buy abstract paintings right now. But you can see that there are some artists out there who are working against the trend. One of these artists will start a new one.”