The Back Room

The Back Room: End of an Era

This week: Russian patrons’ long retreat, Mary Boone’s nonprofit penance, Yves Klein’s proto-NFT, and much more.

This week: Russian patrons’ long retreat, Mary Boone’s nonprofit penance, Yves Klein’s proto-NFT, and much more.

Tim Schneider

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: Russian patrons’ long retreat, Mary Boone’s nonprofit penance, Yves Klein’s proto-NFT, and much more—all in a 7-minute read (1,985 words).

__________________________________________________________________________

Sotheby’s Russian Pictures and Russian Works of Art sales at Sotheby’s on June 1, 2018 in London, England. (Photo by Tristan Fewings/Getty Images for Sotheby’s)

How much do Russia’s mega-collectors still matter to the global art economy? The best answer is “far less than they used to”—an important reality of the trade in 2022 even before the cultural and financial consequences of the war in Ukraine started stacking up.

The ranks of Russian billionaires sanctioned by the U.S. or U.K. now include several top collectors: Roman Abramovich, Petr Aven, Andrey Melnichenko, and more. They can no longer officially buy or sell art, and some lost board seats at prestigious nonprofits like the Guggenheim and Tate.

Auction houses have pledged that sanctioned parties are off limits, too. Last week, Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Bonhams even canceled their upcoming Russian art auctions in London, suggesting the genre itself is untouchable because of its main clientele.

But these moves have been made easier by the fact that Russian money has been a nicety, not a necessity, to the art business for almost a decade, if not more, as Katya Kazakina covered in her latest column.

Russian millionaires and billionaires became “a major force in the market in the early 2000s,” Katya wrote. Their dominance just didn’t last.

At first, their focus was on repatriating Russian trophies. Big auction wins included nine imperial Fabergé eggs from the Forbes family collection, bought by Viktor Vekselberg in 2004 for about $100 million, and the 450-piece art collection of cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, acquired privately by Alisher Usmanov in 2007 for an estimated £20 million. (Both collectors were recently sanctioned.)

The oligarchs pivoted to Western art next. In 2008, Abramovich paid $86.3 million for Francis Bacon’s Triptych and another $33.6 million for Lucian Freud’s Benefits Supervisor Sleeping. Both were auction records at the time.

Dmitry Rybolovlev (still unsanctioned as of press time) spent about $2 billion on blue-chip art between 2003 and 2014, including what Katya called “outrageous” sums for works by Gauguin, Klimt, and Rodin.

No wonder the Big Three auction houses regularly previewed top lots in Moscow, or that Gagosian staged two sold-out pop-up shows there in 2007 and 2008.

Amid the Great Recession in 2008–9, however, many Russian collectors realized they had overpaid for second-rate Western works. The country’s art-industry influence retreated further after several Russian elites were hit with sanctions linked to Putin’s invasion and annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Although insiders say Russian collectors have continued vying for high-level Impressionist and Modern works since then, they no longer have an advantage over deep-pocketed competitors from Asia, the U.S., Europe, and the Middle East.

As metaphors go, it’s almost too much that Rybolovlev bought Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi for $127 million in 2013, then sold it four years later to a Saudi prince for an all-time-high $450.3 million.

Russia’s patrons have also refocused some of their spending on their countrymen’s output. Abramovich is rumored to have paid as much as $60 million for a trove of works by Russian-American Ilya Kabakov; Aven explored founding a private museum in Riga, Latvia to house his impressive holdings of Soviet porcelain and Russian avant-garde art.

Younger buyers also recently started dialing in on Russian contemporary work—a category that rose from almost nothing to about $15 million in sales in 2021, according to Jo Vickery, a London-based advisor and former international director of Russian art at Sotheby’s.

Then tanks rolled into Ukraine, and art-market progress became the least of almost anyone’s concerns.

__________________________________________________________________________

The war is poised to transform the Russian art market, though how much will depend on its level of isolation from other nations afterward. Still, the impact on the contemporary sector will likely be “minimal,” in Vickery’s words, thanks to the broader global distribution of wealth and power.

Top Russian collectors had already largely steered their budgets homeward (and pastward). Russian galleries had not exhibited at Art Basel or Frieze for years. The market for all Russian artwork topped out around $80 million annually, per experts—about the same value as a single excellent Basquiat painting.

So blacklisting oligarchs may not be painless for the rest of the art world, but it sure hurts a lot less than it would have 15 years ago.

____________________________________________________________________________

Mary Boone in 2013. Photo by Neil Rasmus, courtesy of BFA.

The latest Wet Paint reveals that dealer and convicted tax-evader Mary Boone is serving some of her remaining sentence doing community service at Free Arts NYC, a nonprofit providing arts programming and mentorship to the city’s underserved youth.

Also, a Carroll Dunham forgery was pulled from Florida’s Auction Kings ahead of an April 1 sale. The borderline-laughable pass at one of Dunham’s “Wrestler” pieces was estimated to sell for $40,000, a far cry from the $70,000 or so that his works on paper regularly bring by gavel.

Here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Russia-Ukraine Fallout

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

NFTs and More

____________________________________________________________________________

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

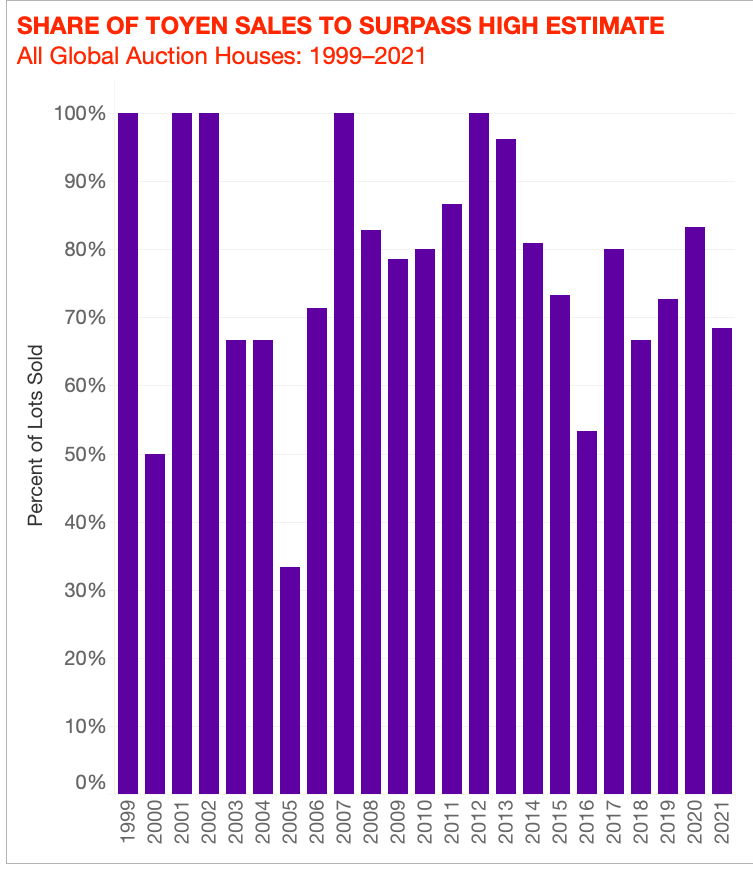

When I learned that a painting by the gender-nonconforming 20th century Surrealist Toyen more than doubled its high estimate to sell for €1.5 million ($1.7 million) at Sotheby’s Paris last week, my reaction was, “I’m sorry, who?”

But if you’re like me, it’s time to get familiar…

For more info on the mysterious Toyen’s dynamic market, click through below.

____________________________________________________________________________

“You don’t need experts in contemporary art. You need an eye, you need an art advisor, but you don’t need an expert. In Old Masters, believe me, you do need experts. I need experts.”

—Eric Turquin, whose firm has managed to certify a slew of unattributed works as genuine Old Masters that went on to sell for millions at auction, including the Chardin still life that soared to a record €24.4 million ($26.8 million) at Artcurial this Wednesday. (Artnet News)

____________________________________________________________________________

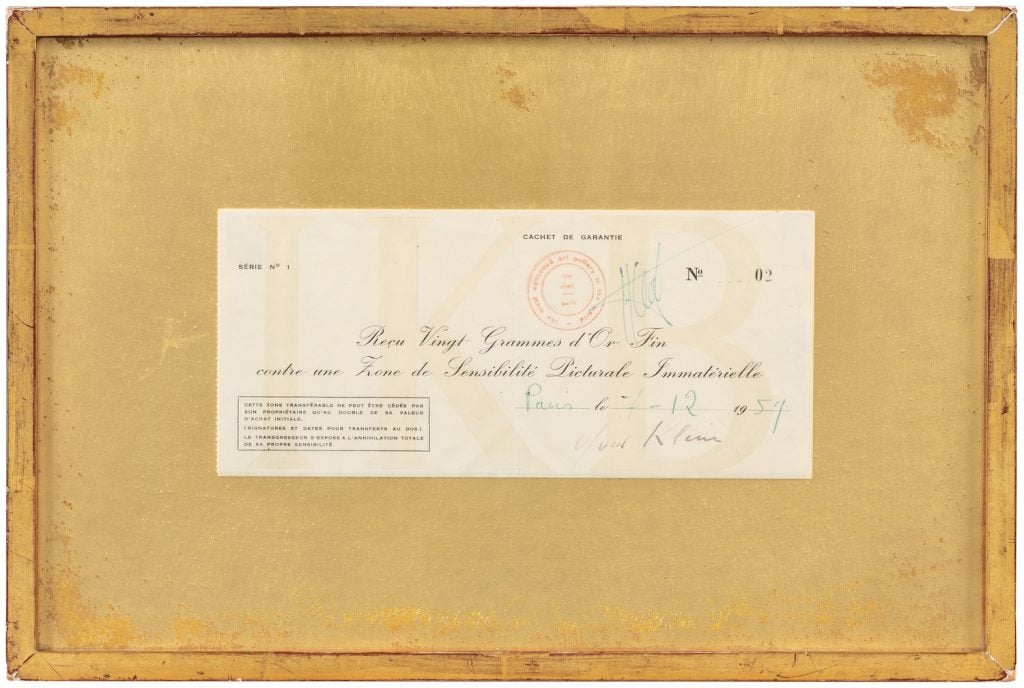

Yves Klein, Zone de sensibilité picturale immatérielle (1959). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

____________________________________________________________________________

Estimate: €300,000 to €500,000 ($331,000 to $551,000)

Selling at: Sotheby’s Paris

Sale Date: April 6

Did Yves Klein beat NFTs to the punch? In 1959, Klein sold his first so-called Zone de sensibilité picturale immatérielle (“zone of immaterial pictorial sensibility”), aka a slice of empty space, in return for a weight of pure gold. What the buyer actually received was a paper receipt certifying their ownership of a specific intangible asset that was otherwise infinitely replicable.

While Klein sold eight more zones before his death in 1962, only a handful of receipts survive today, according to Sotheby’s. This is partly because the artist offered every buyer the choice to participate in a performance that involved burning the receipt and throwing half the gold into the Seine—an act meant to “rebalance the natural order” disrupted by the sale. Some accepted.

But the dealer Jacques Kugel kept his receipt. Over the years, his certificate has been shown at major institutions including the Hayward Gallery, the Centre Pompidou, the Moderna Museet, and the Reina Sofia. Now, it could be yours. The certificate is among the lots being offered by Sotheby’s from the collection of art advisor and curator Loïc Malle, who acquired it in 1994. Just don’t expect Malle to offer to chuck half the sales proceeds in a river, no matter what the winning bidder does with the receipt.

____________________________________________________________________________

With contributions by Naomi Rea.