The Art Detective

How Many Living Women Artists Have Gotten a Career-Defining Survey at the Met? The Answer Will Surprise You

The opening of Cecily Brown's 'Death and the Maid' marks a sea change for women artists.

The opening of Cecily Brown's 'Death and the Maid' marks a sea change for women artists.

Katya Kazakina

I had two burning questions as I air-kissed my way through the glamorous reception for “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this week.

Is she the first living female artist to have a solo show at the biggest U.S. museum in its 150-year history? And was she really wearing the same black, gold chain-neck jumpsuit as Shiv Roy in the Succession episode that aired two days earlier?

It took a while to figure out. No one could confirm with absolute certainty at the opening of Brown’s mid-career survey on April 11. The Met’s director, Max Hollein, gave the first question an agonizing minute, then told me he was drawing a blank. Others had similar reactions.

There must have been precedents, I thought. Vija Celmins had a sublime retrospective in 2019. But, as you may recall, it was at the Met Breuer outpost, not the mothership. The museum has commissioned several living female artists, including Wangechi Mutu, Carole Bove, and Huma Bhabha to create works for its rooftop and façade, but not inside its hallowed halls. That honor was bestowed on Alice Neel, whose acclaimed survey in 2021 was an example of the female artist finally getting her due—albeit 37 years after her death.

Cecily Brown at her opening reception. Darian DiCanno/BFA.com, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

I asked Jeff Koons what it means for an artist to have a show at the Met, since he had one in 2008, just before the financial crisis.

“On the roof,” Koons corrected me. “There were just three works.”

Brown, on the other hand, got two rooms in the modern wing for her 50 paintings and works on paper. It’s a major coup for the artist, who didn’t see critical acclaim and market recognition for years, despite being championed early on by dealers such as Jeffrey Deitch and Larry Gagosian.

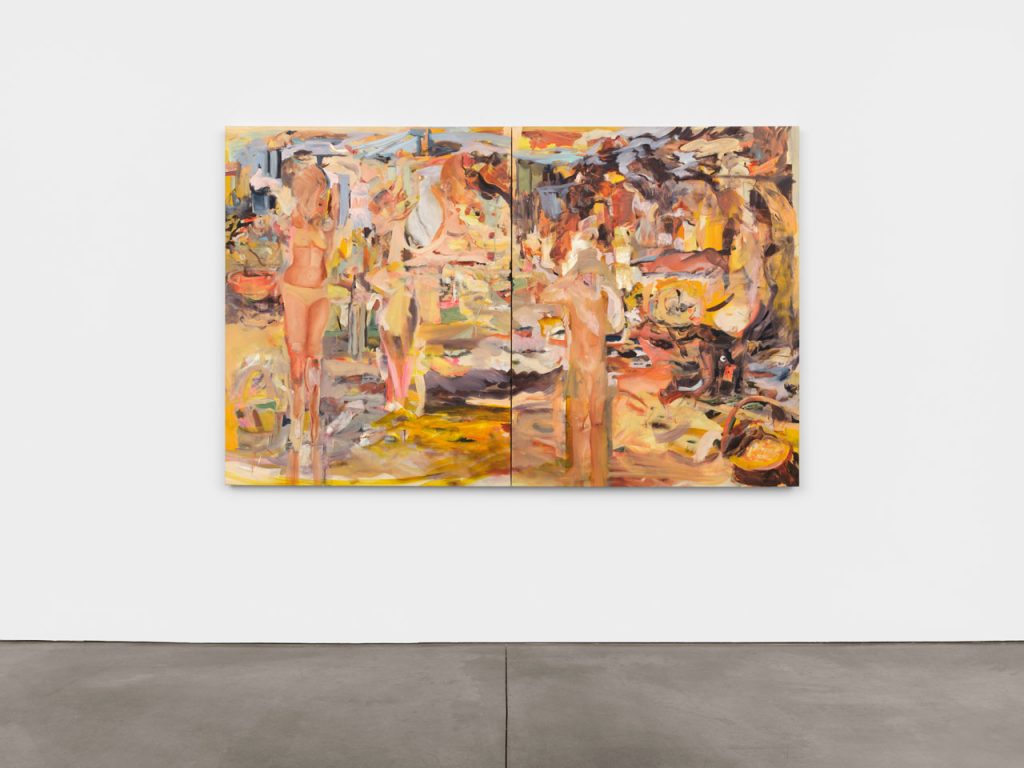

Installation view, “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid,” on view a the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: Paul Lachenauer, courtesy of the Met.

Showing inside the museum is significant for several reasons. “You have a possibility for a large audience to see your work,” Koons said. In 2022, 3.4 million people visited the Met.

There’s also the scope. “Because it’s an encyclopedic museum, your work is being seen in the context of the entire world culture and art history,” Koons added. “That’s a really important part.”

Brown’s show is a case in point. Accessing it requires a walk through the rooms housing the Leonard Lauder collection of Cubist art with its stunning number of Picassos, Braques, and Légers.

Being seen among these and other treasures “has a profound resonance,” said Steven Henry, a senior partner at Paula Cooper gallery, which has represented the artist since 2017. For Brown especially, “Her work is so imbued with art history and the knowledge and awareness of the traditions and artists before her. It also expands on that in a radical way.”

Visitors taking in “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Darian DiCanno/BFA.com, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Curated by Ian Alteveer, “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid” spans 25 years and focuses on the themes of beauty and death. Many works relate to others in the Met’s collection. While the canvases may initially appear abstract, Brown begins by painting a figure, landscape or still life. Often buried amid a torrent of vivid brushstrokes are references to famous and obscure Old Masters.

Brown said she is humbled by the experience. Coming to the museum on the morning when the show’s massive banner was unveiled on the Met’s façade set off “butterflies in my stomach,” she told me.

The Met’s imprimatur gives Brown, 53, a coveted spot atop the art world food chain. The recognition has been long coming. Born in London, she moved to New York in 1994 and was soon showing her paintings of bunny orgies at Deitch Projects in SoHo. In 2000, she joined Gagosian’s rapidly expanding empire; but her very first show there was panned by Roberta Smith in the New York Times.

Cecily Brown, The Splendid Table (2019–20). Private collection, Texas, promised gift to a U.S. museum. Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery.

By 2008, her primary market prices ranged from $100,000 to $700,000. Auction results were erratic, spiking to a total of $10 million in 2010, then dropping to a mere $614,490 in all of 2016.

Her move to Paula Cooper ushered in a period of stability and acclaim. These days, primary prices range from about $125,000 to $1 million; two 26-foot-wide tableaux (consisting of three panels each), which were showstoppers at Paula Cooper’s exhibitions in 2017 and 2020, sold for $3 million each. The earlier one was acquired by billionaire Mitchell Rales and is currently on view at Glenstone, his private museum in Potomac. The second was purchased by a Texas-based collector and is being donated to a U.S. museum, according to Henry, who declined to reveal any details. A smaller two-panel painting, Nudity. Language. Smoking (2023), is being acquired by the Norton Museum of Art in Palm Beach.

Cecily Brown, Nudity, Language, Smoking (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Paula Cooper Gallery.

Brown’s auction market surged seemingly overnight. In 2017, it hit $14 million, more than doubling the following year. These days, Brown is second only to Yayoi Kusama among living female artists, according to the Artnet Price Database. In 2022, Brown’s works generated $33.1 million at auction, after peaking at $35.5 million in 2021. The most expensive work, Suddenly Last Summer (1999), sold for $6.8 million at Sotheby’s in 2018, and four other paintings have fetched more than $6 million since then. It should be noted, however, that according to last year’s Burns Halperin report, auction sales since 2008 by women artists totaled $6.2 billion—roughly the same as those for Pablo Picasso alone.

The impact of the Met’s show on Brown’s market will be tested in May. Sotheby’s is offering her 2015 painting Free Games for May from the collection of Mo Ostin, estimated at $3 million to $5 million, a comfortable range which has accounted for 16 auction results in the past five years. One measure of interest in her work—searches for “Cecily Brown” on the Artnet Price Database—tripled to 658 in March from 177 in August.

The artist is ambivalent about her commercial success, telling the Financial Times in 2020: “I don’t actually think any work of art by a living artist should be more than a million dollars. I think it’s sick. It’s out of control. It’s about big-dick contests and it’s about all the wrong things.”

Cecily Brown, Suddenly Last Summer (1999). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

The Met’s show validates Brown as an artist beyond the market, a rare and coveted spot. In 2006, Betty Woodman, then in her mid 70s, became the first woman artist to get a retrospective at the Met during her lifetime. The museum has featured only 13 living female artists in its solo exhibitions and commissions since 2010, according to a spokeswoman.

After dissecting the list, the Art Detective can confirm: Brown is the first living female painter to receive the accolade inside the museum’s main building.

(Three artists showed on the roof, two on the façade, and two at Met Breuer; four others contributed specific works in video and sculpture. Japanese fashion designer Rei Kawakubo was presented by the Costume Institute and Janet Cardiff showed her sound installation at the Cloisters.)

The opening reception for “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: Katya Kazakina.

Interestingly, Brown joins three other women with significant solo exhibitions in New York museums: Sarah Sze at the Guggenheim; Wangechi Mutu at the New Museum; and Jaune Quick-to-See Smith at the Whitney. The range of their work is as diverse as their backgrounds—and unprecedented in the city’s cultural life.

“It’s the dawn of a new era,” said Lisa Phillips, director of the New Museum. I ran into her two nights in a row this week, first at Brown’s opening, then a few blocks north at LGDR gallery, where another female artist, Marilyn Minter, had a big first. Her large-scale painting Word of Mouth sold for more than $1 million, crossing that mark for the first time and especially notable since her auction record is just $269,000, the gallery said.

Could Phillips remember another time when four major New York museums gave living female artists sprawling retrospectives at the same time? She could not.

“The world is coming around and finally recognizing that there are so many great female artists who haven’t gotten their due,” she said.

Perhaps that sense of change, decades and even centuries in the making and suddenly self-evident, infused the night at the Met.

Will Cotton, Rose Dergan, Sophia Cohen, and Dana Schutz attend the opening of “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid.” Photo: Darian DiCanno/BFA.com, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The art world came out in force to celebrate. Champagne was passed around the Petrie European Sculpture Court, the bubbles dancing giddily in the glow of the neon uplighting. Artists on hand included Koons and Sze, Julian Schnabel and Dana Schutz, Will Cotton and Leo Villareal, Glenn Ligon and Jessica Craig-Martin, Christopher Wool and Charline von Heyl.

Brown, resplendent in that halter-neck, backless jumpsuit, offered hugs and kisses.

Also on hand were Oscar Tang and Agnes Hsu-Tang, who gave the Met $125 million, its largest capital gift, to reignite efforts behind the new modern art wing. Klaus Biesenbach chatted with Marina Kellen French, whose 2021 gift created an endowment for the Met’s directorship, and Linda Macklowe, whose epic divorce from real-estate developer Harry Macklowe resulted in a $900 million auction. Anna Wintour and Huma Abedin found a quiet spot by Rodin’s Burghers of Calais.

Huma Abedin, Met director Max Hollein, and Anna Wintour at the opening reception for “Cecily Brown: Death and the Maid.” Photo: Darian DiCanno/BFA.com, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

What better authority than Vogue’s editrix to inquire about my second burning question: Brown’s jumpsuit and its relationship to the Succession series? Wintour peered at me through her signature sunglasses and said she didn’t know because she didn’t see the artist.

Brown, it turns out, wore Celine, the Met spokesperson later confirmed. The seemingly identical outfit worn by Shiv, the heiress we love to hate, paired a Tom Ford tuxedo with a gold halter-neck top by Aqua from Bloomingdale’s, according to a Warner Media publicist.

Sarah Snook as Shiv Roy in HBO’s Succession. Photo: Macall B. Polay/HBO.

Mystery solved.

More importantly, Brown’s Met exhibition seems to have converted some of her harshest critics. Two days after the reception, Smith published a glowing review in the New York Times.

Its headline: “I Was Wrong About Cecily Brown.”