The Gray Market

Why Auction Houses Might Keep One Foot Off the Crypto Bandwagon After a Volatile Year (and Other Insights)

Buyers take on more risk with crypto payments than auction houses do.

Buyers take on more risk with crypto payments than auction houses do.

Tim Schneider

Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, the ups and downs of stepping into new frontiers…

In the past year, all of the Big Three auction houses have agreed to accept payment in cryptocurrency for one or more major physical artworks. For several months after the first instance, the escalating prices of Bitcoin, Ether, and even various alt-coins upped the pressure on the gavel gang to hurry the sector into the future promised by blockchain evangelists: one in which cryptocurrencies would be fully integrated with all levels of the larger economy, including the high end of the market for tangible art.

One year later, however, cryptocurrency prices are radically down from their 2021 highs amid a broader decline in the financial markets. Just as important, New York’s freshly concluded spring auction cycle shows that Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips are proceeding with caution when it comes to blockchain-based payments for physical works. The fine print governing these transactions also clarifies that merging the art and crypto economies demands traveling a path with more switchbacks and detours than either side may have anticipated during last year’s run-up.

Let’s rewind. In early May 2021, Sotheby’s announced that it would partner with Coinbase, the prominent U.S. crypto exchange, to enable payment in Bitcoin or Ether for Love Is in the Air, a 2005 Banksy painting included in its spring contemporary evening sale in New York later that month. The house stated that the sale would mark the first time an auction house would accept cryptocurrency for a physical artwork, not an NFT.

The move didn’t come without risks, but the upside likely looked too great to turn down. At the time, one bitcoin was worth about $59,000, and one ether about $3,900. Both values were at or near the highest they’d ever been. The auction sector was also only about five weeks removed from seeing Beeple’s NFT-backed digital collage Everydays – the First 5,000 Days sell for $69.3 million, a gargantuan sum ultimately paid in cryptocurrency, according to Christie’s. If Web3 plutocrats were eager to fork over tens of millions of dollars worth of Bitcoin or Ether for an NFT, then why wouldn’t they be willing to do the same for the right painting, especially with so much new crypto wealth sloshing around the economy?

Love Is in the Air ultimately hauled in a premium-inclusive $12.9 million, more than two and a half times its $5 million high estimate. (Reminder: presale estimates exclude premiums.) Although Sotheby’s declined to comment on whether the winner actually paid in crypto, the house must have believed that giving bidders the option benefited the house (or at least didn’t hurt). The strongest indicator? Sotheby’s went on to offer crypto-payment capabilities on two more Banksy paintings in its rebranded “The Now” evening sale in New York in November 2021.

Ramping up made sense. Although the prices of Bitcoin and Ether both plummeted during the summer of 2021, they bounced back in the intervening months to reach new apexes (of $64,400 and $4,644, respectively) less than a week before the house’s marquee fall sales. Sotheby’s move once again correlated to healthy results for the Banksy works: another version of Love Is in the Air sold for $8.1 million against a $6 million high estimate, and Trolley Hunters (2006) went for $6.7 million after fees, close to its top expectation of $7 million.

Since last May, Christie’s and Phillips have joined Sotheby’s in accepting cryptocurrency for certain physical artworks, including in the two-week cycle we just completed. But the value proposition looks different against this year’s ongoing economic turbulence, with crypto prices absorbing outsized damage. As of noon this past Tuesday, the price of one bitcoin had declined to $28,900, and one ether to $1,957—both down more than 55 percent from their November summits. Each daily news cycle seems to harbor a fresh crypto-based scam, even among mainstream media outlets. Everyday people who rocketed into the ranks of the crypto wealthy during 2021 are now sharing tragic stories about vaporized life savings, suddenly unpayable mortgages, and the darkest personal exit strategy of all.

Has the new gloom around cryptocurrencies affected the Big Three’s position on accepting them for major paintings and sculptures, not just NFTs? To find out, I combed through Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips’s lot lists and conditions of sale for this May’s evening auction slate. Below are my top three takeaways.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled (1982). Image courtesy Phillips.

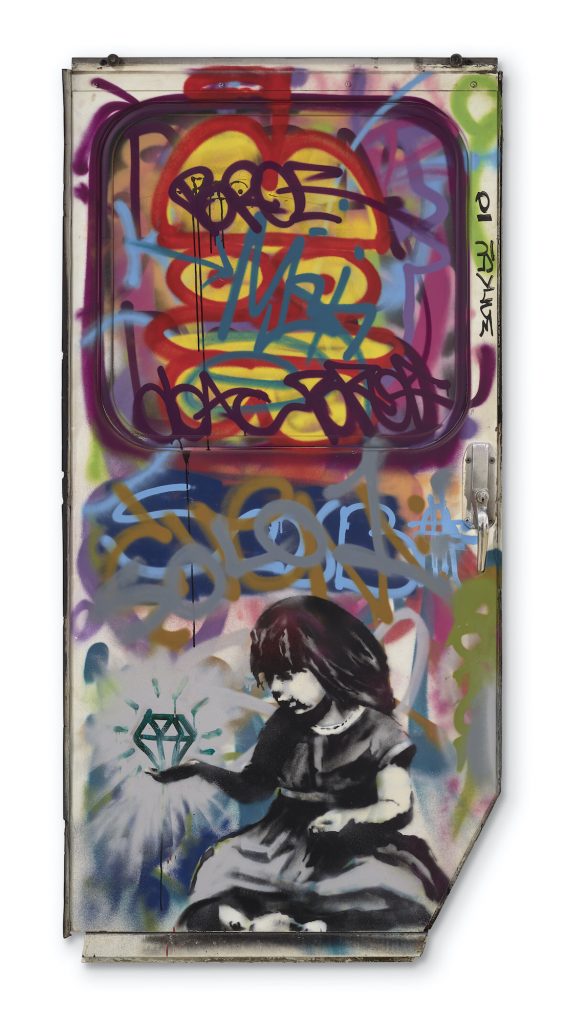

In the most recent round of New York auctions, Christie’s OK’d payment in Bitcoin or Ether for the 2011 Banksy painting Diamond in the Rough, offered in its 21st century evening sale. Phillips did the same for its 20th and 21st century evening auction’s premier lot, the untitled 1982 Basquiat canvas consigned by Japanese billionaire Yusaku Maezawa.

But just as interesting was who didn’t enable crypto payments this time: Sotheby’s, the house that kicked off the trend a year ago. Not a single lot in its evening sales of Modern art, contemporary art, or art of “The Now” could be settled up with blockchain-backed money—not even the Banksy painting This Is Not a Photo Opportunity (which sold for a premium-inclusive $2.7 million in “The Now”).

It’s unclear why Sotheby’s decided to abstain during this round after its enthusiasm in 2021 and its competitors’ advances in 2022, but signs from elsewhere suggest the best answer may be simple lack of interest from clients. Phillips required bidders to declare their intention to pay with cryptocurrency before the Basquiat sale opened; none did, according to a Phillips spokesperson. Christie’s declined to comment on whether the winner of Diamond in the Rough paid in Bitcoin or Ether, citing client confidentiality. Combine those facts with Sotheby’s demurral on the winning bidders’ payment method for Love Is in the Air last May, and we are left with no compelling evidence that accepting crypto payments in select cases has done much for each house’s bottom lines. That possibility could make this experiment a short-lived one for the Big Three.

Banksy, Diamond in the Rough (2010). Courtesy of Christie’s Images Ltd.

Volatility is the gift and the curse of cryptocurrencies. Even Bitcoin and Ether have valuations that move more like a caricature of tech stocks than like the dollar, the pound sterling, or other major fiat currencies. And since cryptocurrencies trade 24 hours a day, seven days a week, a significant price swing could happen at any time. As a result, paying for anything with crypto takes on a casino-esque dimension that fiat currencies generally only match if they spiral into hyperinflation (see: Argentina).

For example, suppose that the buyer of Banksy’s Diamond in the Rough at Christie’s wanted to use bitcoin to cover the $3.7 million final price this Tuesday. Within about two hours that afternoon, the value of one bitcoin changed by nearly $800, or 2.8 percent of its total value at the day’s nadir. This means the difference between completing the transaction at 2:15 p.m. versus 4:15 p.m. would have been about $103,000. And Tuesday qualifies as a pretty stable day in Bitcoin relative to its price plunge since early April.

Fiat currencies don’t zero out the stakes of (mis)timing the market from moment to moment, but they reduce it substantially. For comparison, the largest spread in the exchange rate between the dollar and the pound sterling on Tuesday was about one percent. So if the buyer of Diamond in the Rough needed to convert U.K. currency to U.S. currency to complete the transaction (all three houses require buyers to pay in the native currency of the salesroom where the physical work was offered), the maximum difference in their final price would only equate to about $37,000—an order of magnitude less than the difference they could have faced by paying in bitcoin.

In theory, the auction houses play the same game of chance once they receive a payment in crypto, only on an even longer timeframe. Buyers paying for a physical work in cryptocurrency must remit the total balance due within somewhere between 48 hours and 10 days from the auction’s end, depending on which of the Big Three is on the receiving end. The houses, on the other hand, could theoretically hold a cryptocurrency payment in their crypto wallets for as long as they were willing to brave the market. Considering that we saw the prices of major cryptocurrencies double in as little as four months last year—and get cut nearly in half in five weeks—it creates a fascinating new risk calculus to manage for high-priced artworks.

Banksy, Trolley Hunters (2006). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

Setting aside exchange rates and the volatility of crypto prices, a close read of Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips conditions of sale show they have (wisely) worked to firewall themselves off from as many uncertainties of the crypto ecosystem as possible. To me, it also reveals how the auction houses’ version of decentralized payment can be the worst of both worlds for bidders: a myth in some respects, and a harsh reality in others.

First, it’s not enough for prospective crypto bidders to simply prove to the houses that they hold a sufficient amount of Bitcoin or Ether in their crypto wallets to compete for a given artwork. They also have to meet the same standards related to anti-money-laundering and know-your-customer protocols as fiat bidders; warrant that their crypto wealth was legally earned and remains free of any liens or criminal ties; and in at least one past case, verify that they reside in a country where crypto trades are permitted (primarily meaning “not China”).

In addition, all three houses only accept payments from crypto wallets under the custodianship of the same five platforms: Coinbase, Coinbase Custody Trust, Fidelity Digital Assets Services, Gemini, and Paxos. The wallet in question must also be registered to an individual physical bidder or a legally recognized entity (such as a corporation) on whose behalf that physical individual is authorized to bid. Phillips’s conditions of sale for cryptocurrency payments even state that prospective crypto payers may be required to do a “recorded video call with Phillips staff” to verify their identity and wallet ownership; they also explicitly ban decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) from registering as bidders (another contrast with Sotheby’s).

What unites all of these stipulations? They eliminate the anonymity, “trustlessness,” and rejection of central authority that were supposed to be the lifeblood of the crypto economy. From a legal and regulatory standpoint, it’s the only way for the houses to tiptoe into this territory.

At the same time, bidders who accept these conditions are still left to contend with the greater risks of blockchain systems on their own, starting from the moment a lot hits the block. Spokespeople from Sotheby’s and Phillips noted that the on-screen currency converters used during live bidding omit the equivalent amounts in accepted cryptocurrencies; this means competitors planning to pay for a lot with blockchain-based money must do their own math to keep themselves within their budget. (The final balance due is calculated automatically on either the invoice or a payment link sent after the sale concludes.)

More broadly, the houses expressly warrant that they bear no responsibility for any events or conditions that might interfere with a buyer’s attempt to pay in an accepted cryptocurrency, from technological glitches to operator error. In some cases, should bidders miss the cryptocurrency payment window, they will be required to pay in the fiat currency of the applicable auction salesroom.

Sotheby’s conditions of business and other terms applicable to sales are even “subject to change until a lot is sold to a buyer,” a house spokesperson stated. In other words, even if Sotheby’s had announced in advance of an auction that it would accept crypto payment for one or more works, it reserves the option to say, “Actually, nevermind!” until a deal is actually complete. Seems like a handy failsafe in the event of a crypto market crash, doesn’t it?

A “physical Bitcoin” (which is sort of a gimmick, but exists). Photo Illustration by Thomas Trutschel/Photothek via Getty Images.

After absorbing all the facts, conditions, and caveats above, more than one person reading this column is probably asking themselves whether transacting in crypto for physical works is really worth it to either bidders or major auction houses. It’s a fair question, particularly against the backdrop of the crypto market’s latest dive bomb. Still, it’s worth remembering that building this payment architecture is a potentially lucrative new customer acquisition tool for the Big Three auction houses.

Fourteen years after the Bitcoin white paper emerged, vanishingly few merchants in any sector can transact in cryptocurrencies, forcing Bitcoin and Ether tycoons to go through the headache of converting blockchain-backed money into fiat funds almost any time they want to purchase anything. To me, one of the strongest engines behind NFT prices’ blastoff during much of 2021 was that they were one of the few assets that crypto wealth could actually buy directly with their then-growing stockpiles of Bitcoin, Ether, and alt-coins.

By enabling crypto payments for high-value physical artworks, the Big Three auction houses give blockchain barons another legal outlet for their digital cash in what remains a wasteland of options. At the same time, the houses have also armored themselves against as many perils of the crypto economy as possible. The result: maximum upside, minimum downside, and the ability to pull the plug on the experiment at any time.

The longer the cryptocurrency rout continues, the more worthwhile it will be to watch how willing Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips will be to accept Bitcoin and Ether in upcoming marquee sales. Blockchain evangelists will say it’s still early days for the synthesis of crypto and the high-end art market; blockchain critics will say this could be the beginning of the end. But if the past year has taught me anything, it’s that neither outcome is likely to proceed in a straight line from where we are now.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: If you want to know what someone really thinks about a deal, read the fine print.