Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, testing the line between talking about it, and being about it…

MYSTERY CUBE

Corralling the public’s attention for anything is murderously hard in the neverending monsoon of distraction that is life in the social-media-and-disinformation era, and the challenge only increases in the art world, where nearly everything is subjective. In short: godspeed you, art press pros. And to your many clients and in-house employers: I understand why you’re alchemizing increasingly elaborate preview events, video walkthroughs, and other spectacles to try to focus attention on your program. When the competition cranks the volume, the obvious response is to amp up your own output.

Amid this sound clash, it’s all the more noteworthy when two New York art dealers with significant solo track records announce their new joint gallery with not much more than a passing remark and a shrug. That was how the art world at large learned about Egan and Rosen just four days before the premiere of its inaugural exhibition on July 29. The Upper East Side project is an alliance between Mike Egan, the founder of the bleeding-edge gallery Ramiken, and Meredith Rosen, whose namesake space has toggled between tech-forward world-building, conceptual provocations, and of-the-moment themes expressed in traditional media.

It’s plausible that even some plugged-in readers are only learning that Egan and Rosen exists right now because its partners tossed most of the conventional “How to Launch a Gallery in 2021” playbook into the gutter. The founders decided to open in what’s traditionally seen as a sweat-soaked dead zone on the art-world calendar. Then they messaged it via a single email with no follow-up (or at least none that I’m aware of).

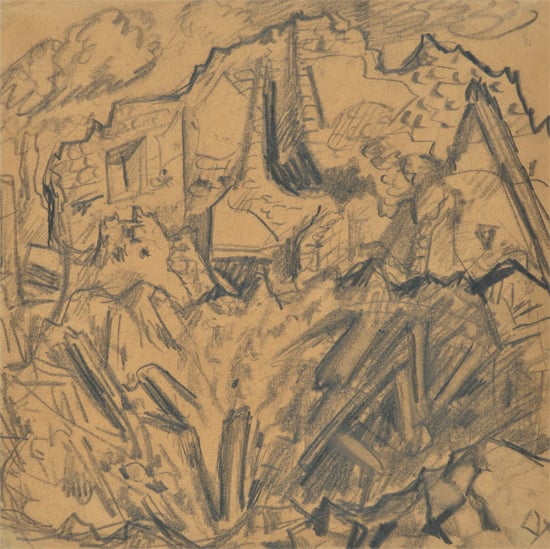

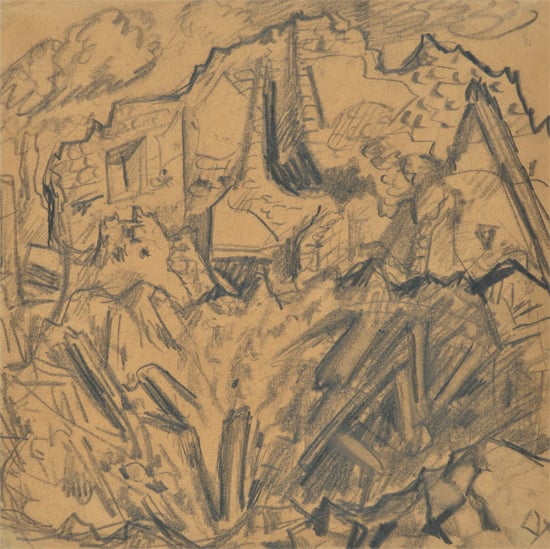

The email included one small embedded image, a few line items of basic info (location, hours of operation, etc.), and a two-sentence description of their debut exhibition, “Otto Dix / Andra Ursuţa.” The show pairs a selection of Dix’s wartime sketches (one of them anticipating his revered “Der Krieg” cycle) and portraits of Weimar Germany’s trauma-haunted hedonism with drawings from Ursuţa’s “Man From the Internet” series, adapted from online images of a decaying victim of Russia’s war against Chechnya in the 1990s.

Andra Ursuţa, Man From the Internet 73 (2016). Courtesy of Egan and Rosen, New York.

The gallery’s website hosts even less content. In comparison, the 12 posts on its Instagram as of publication time feel like acts of lurid exhibitionism, which is even more ironic given that several are accompanied by either no caption at all or just the hashtag “#ottodix.” The account had 277 followers when I filed this piece, meaning 276 other than me. If I didn’t know better, I would have bet the gallery would have attracted hundreds, if not thousands, more virtual fans based purely on the presence of Ursuţa, whose most recent show of ethereal sculptures with Ramiken was one of the most universally admired New York exhibitions of 2019. (The artist signed with David Zwirner last summer.)

(If you’re wondering, Ramiken’s Instagram has an audience of more than 3,000, and Meredith Rosen Gallery has just shy of 31,000, meaning only a splinter group of the cofounders’ pre-existing fans have followed the trail of breadcrumbs to Egan and Rosen’s social presence to date.)

The week of the partnership’s debut, I reached out to Rosen to confirm whether it was a full-on merger of her gallery and Egan’s, or a new venture that would co-exist independent of her namesake space and Ramiken. Her answer was the latter (which I noted in that week’s edition of the Back Room). After another two weeks passed with Egan and Rosen seeming satisfied to continue hiding in plain sight, curiosity prodded me into seeing if they would elaborate on what, exactly, they’re up to with their space on 78th Street. The result is the interview below, conducted by email over the weekend. (Questions and answers have been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.)

It should surprise no one that Egan and Rosen were selective about the details they divulged. But I think their answers at least bring the gallery into soft focus as a shape-shifting child of productive internal tensions and mutual disinterest in the rote professionalization that has defined too much of the art world lately. In other words, Egan and Rosen seems intent on being a gallery where the best—and nearly the only—way to understand what’s going on is to actually go. In an art trade that too often feels like a high-velocity, high-decibel assembly line clamoring for your attention, there’s more than a little wisdom in that approach.

Otto Dix, Grenade Crater in a House (1916). Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne, New York.

Let’s start here: Instead of a full-fledged merger that marries your two programs together in all aspects, Egan and Rosen is a separate venture the two of you are operating independent of Meredith Rosen Gallery and Ramiken. It has its own space and (unless I’m missing it) no gallery roster to speak of. How would you define the parameters of, and the concept shaping, Egan and Rosen? In other words, what’s the overall vision, and how do some of the organizational details work (e.g. Will every show be a joint programming decision? Will you team up for art fairs or offsite projects? Do you just share all costs and sales proceeds equally?)

Meredith: Every show is a joint programming decision. We plan to do it all, fairs included.

Mike: I went diving to look at these pre-Roman sculptures, submerged off the coast of Naples, and it turned me on to a certain kind of algal existence, and I thought about how we could be like that algae, and as time floods our existence with meaning, perhaps we have to start breathing water, and grow on this shipwreck we call civilization. In ancient sculpture from the Ukraine river valleys, the goddess culture where the sculpture itself is the real thing, there is no representation or false move—because representation leads to perfectionism.

So we do represent artists, but we’re not going to list them online. Now with these things in mind, a lovely punk gallery with charming manners and a thirst for blood makes a lot of sense on the Upper East Side right now. Everybody is going to love it. The gallery is set up so we can do the shows we want to do. I feel that Met energy, that Neue Galerie breakfast magic.

Each of you are now running two businesses: Egan and Rosen, and then your pre-existing spaces yourselves. That seems to fly in the face of the conventional wisdom that teaming up with another dealer is valuable in large part because it allows you to share resources and costs to make the very hard job of running a gallery somewhat easier. Why did you decide that this arrangement was the best way to join forces?

Mike: We both agreed that there were certain things that were becoming necessary to do, and this was going to be the gallery to do those things. We share some of the same hallucinations. Similar delusions too. Different pathos. Different addictions, but complementary: coffee vs. psilocybin. Economically, it’s very simple, and we both like the math of paid artists.

Andra Ursuţa, Man From the Internet 72 (2016). Courtesy of Egan and Rosen, New York.

Boring question, but I’m required by journalistic law to ask: Did the pandemic and its after-effects play any role in convincing the two of you to launch Egan and Rosen when and where you did? If so, how? If not, why did you feel this summer was the right moment?

Mike: I was on the mainland when the ‘vid popped off. Luckily, I got out, and Meredith saved me, pulled me out the gutter, and showed me this space with leopard print carpet that I fell in love with, and I really just don’t want to disappoint her. So I’m gonna work really hard, and I’ve shared all my client info with her. And it turns out we both sell to the exact same 300 people.

Is the current Egan and Rosen space on 78th Street going to be the gallery’s permanent location, at least for the time being? Either way, what aspects convinced you both it was the right location? It’s obviously right around the corner from your gallery, Meredith, but the U.E.S. is a very different context than people tend to associate with Ramiken, Mike.

Meredith: Yes, 11 East 78th Street is the permanent location for Egan and Rosen.

Mike: I’m not killing giant rats anymore like I was in 2009 down on Clinton Street. I had a gallery in Nichols Canyon in Los Angeles that was perfect, but only seven people came. Then I was squatting in a penthouse on 81st Street for a year and a half, but the parties got too big.

The Egan and Rosen space is perfect. Meredith found it. When it comes to galleries, the space just has to come at the right time and do the shows it was meant to do. Our vibe is: Go to the Met, then come to Egan and Rosen. That’s an art experience I can believe in.

Mike Egan, Lo peor es pedir (2021). Courtesy of Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York.

Meredith, this spring you did a solo show of Mike’s artwork, a polaroid series of Lana Del Rey’s face that he warped by contorting his body while wearing a t-shirt with her image. What was your relationship like prior to that exhibition? How, if at all, do you think the experience of working together on a dealer-to-artist level has (or will) factor into your partnership as co-dealers/co-exhibitors? (Mike, this question is just as much for you as Meredith. It was just weird to introduce it differently than this.)

Meredith: Artists’ whole lives are continuous with their work. Mike as an artist informs Mike as a dealer. We had a great experience working together on “Lana”. The show sold out very quickly and had an unbelievable response from the public. I’m looking forward to his next show at M.R.G.

Mike: I can be a difficult person, but every second of my show at Meredith’s gallery was joyful. I desperately need to learn how she does that. I was a big fan of Tina Braegger’s paintings, and that made me want to show with Meredith. A gallery show next to the Met is a dream come true for every artist.

Technically speaking, Egan and Rosen qualifies as an expansion of sorts in a gallery business that has for years now gravitated toward the idea that the default solution is “bigger, faster, more.” At the same time, based on what I know of you and your respective careers, I suspect “expansion” is a somewhat lazy way of framing what you’re aiming to achieve with the new venture. What do you think working together on Egan and Rosen can help you do first and foremost for the artists you’ll work with, but also for your own goals, in the art world as it exists in 2021?

Meredith: Working with artists is the thing I love about being an art dealer. Egan and Rosen is a space without constraints: secondary, primary, historical, special projects, just good shows. There are no rules, and we thrive on that. It’s exciting to me to create something new, something that doesn’t fit in pre-existing categories. The great thing about working with artists is they’re always pushing themselves to the next frontier, and I feel the same way as a gallerist.

Mike: I’m a collector, and this job feeds my need to acquire. I have a Dix etching from “Der Krieg” and a “Man from the Internet” next to each other in my apartment. This gallery is how I form my collection philosophy, and working with Meredith on the gallery puts the art I want in reach.

If there’s a goal other than to do the shows we each want to see, it’s to make a gallery that people love, or love to hate. I care about the work. I also care about the artists and the love of their fans. I don’t have any other goals. All the structures in the art world are less than a hundred years old, and in a hundred years there will be completely different ones. We’re supplying the future with the raw materials for their new art world.

Otto Dix, Reclining Female Nude, Half Figure (1929). Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne, New York.

Can you give me any hints of what’s coming up for the gallery in the future?

Meredith: In September, we’re opening a show of two paintings from the mid-‘90s by Takako Yamaguchi from her “Smoking Women” series.

… And there you have it, folks. A small part of me wishes I could give you some grander takeaway about what to expect from Egan and Rosen, but the larger part of me is convinced that my inability to do so is the most promising sign of all.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: “show, don’t tell” is advice that applies to more than just writing and making movies.