Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, closing the loop…

ALL THAT GLITTERS

With roughly six weeks of the year left, it’s hard to imagine another art-market rumor spreading as rapidly or as breathlessly through 2022 as last month’s talk that LVMH was about to acquire Gagosian. The consensus among art-world observers at the time was that the prospect made too much sense not to happen.

Roughly three weeks later, however, the gossip seems to be a cross between a misinterpretation and a mass delusion. There are two reasons why, in retrospect, this outcome was always more likely—and it’s worth remembering them the next time the art world starts buzzing about a luxury conglomerate buying into the gallery sector.

First, though, let’s nail the casket closed on the LVMH/Gagosian rumor. Gagosian spokespeople have denied it up, down, left, and right since it emerged during the inaugural Paris+ fair in late October. An alternate theory (first reported by the Canvas, then expanded upon by my colleague Katya Kazakina) holds that the real deal linking the two parties is a $1 billion credit line empowering Larry Gagosian to make strategic artwork buys on behalf of LVMH’s billionaire founder, Bernard Arnault. (Representatives for Gagosian and LVMH didn’t respond to Katya’s requests for comment.)

Could Arnault have been the end client for Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn (1964), which Gagosian won for $195 million at Christie’s auction this May? We may never know the answer.

What we do know is, that three weeks after many art pros were holding their breath for confirmation that LVMH was about to buy Gagosian outright, there have been no outward signs that the two companies are marching toward a terms sheet. I can’t picture them—or any of their respective competitors—getting there anytime soon, either. The road has a couple of major obstacles that seem to have stayed out of view during the most active part of the gossip cycle.

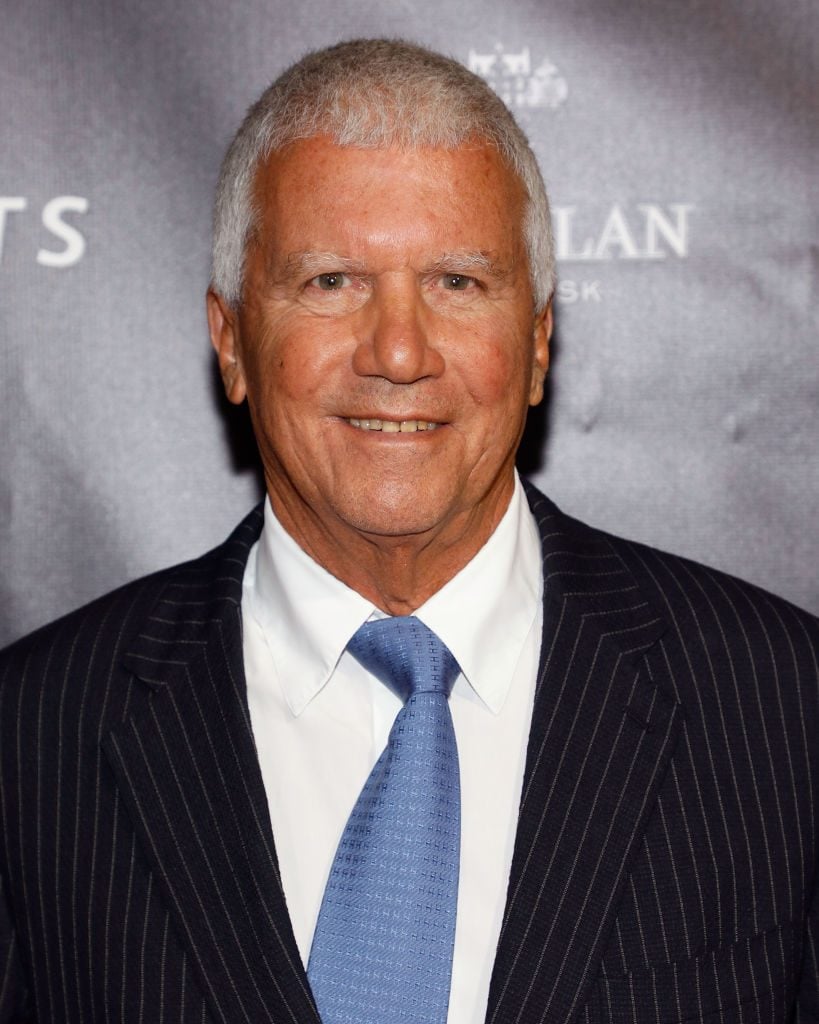

LVMH CEO Bernard Arnault. (Photo by Sergei KarpukhinTASS via Getty Images)

CULTURE CLASH

I spoke to Doug Stephens, an author and longtime consultant to top-tier retail and luxury brands, to get a different perspective on the feasibility and mechanics of a luxury behemoth adding a mega-gallery to its portfolio. Stephens, I should note, said he had not heard a peep about LVMH acquiring Gagosian until I asked him about it in early November. While he too thought that a deal like it made a lot of sense, he also emphasized that practically every merger or acquisition does during negotiations, including the ones that later flame out once the businesses are actually tied together.

“Most acquisitions don’t fail on the numbers. They just don’t,” Stephens said. “Where they often fail is culturally.”

Take LVMH as an example. The company reported €36.7 billion ($38.2 billion) in revenue and €10.2 billion ($10.6 billion) in profit during the first half of 2022. You don’t have to be an economist to understand that figures that size put the conglomerate in the big leagues… which also means every significant move it makes must be methodical.

For a company of LVMH’s caliber, no potential acquisition can advance until it has survived a gauntlet of due diligence appraisals from analysts and attorneys. The stakes are too high to do anything less. What this means is that “nine times out of ten, these deals do make sense on paper from a revenue, profitability, and strategy standpoint,” Stephens said.

And yet, just like in the art market, the data is only one part of the story. How a smaller company is integrated into a larger one is just as important as whether a smaller company is integrated into a larger one. The human element, personnel, internal systems, and workflows all matter. And all of the above matters even more when the company targeted for acquisition has become successful in large part because of its founder’s unique vision and energy (as, I think it’s safe to say, Gagosian has).

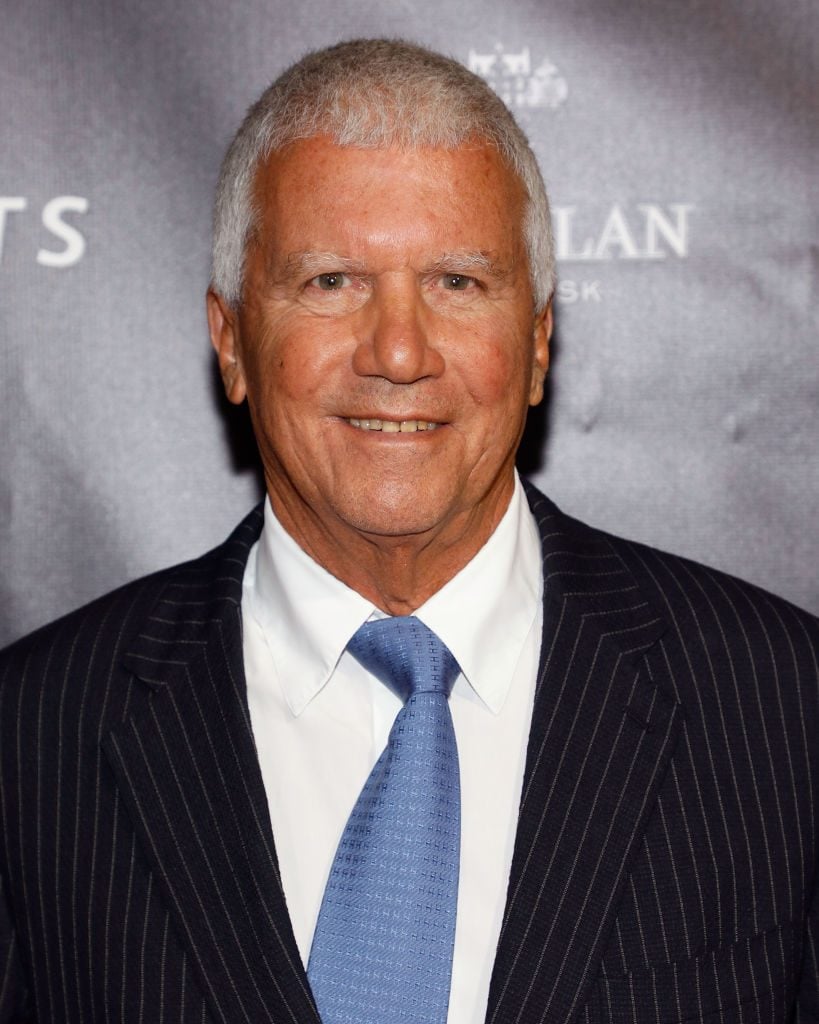

Larry Gagosian. (Photo by Taylor Hill/FilmMagic)

“Founder-led companies often have a remarkable acuity for zeroing in very closely on what customers want and harnessing all the resources of the company to give them what they want. That’s how tiny companies become bigger companies,” Stephens said. “What can happen when a founder-led company is brought into a conglomerate, especially if the founder is marginalized in the process, is that what drove the company and made it great sometimes gets watered down.”

In the worst cases, middle managers’ thoughts on the company’s value proposition and strategy begin to crowd out the founder’s intense focus on the client experience. In turn, decision-making slows down and people work to mitigate risk rather than embrace it strategically.

In fact, Stephens notes that shareholders in a planned acquisition can actually sue the parties involved if they believe there was a “reckless disregard” for the deal’s effects on company culture. This means executives on both ends of any possible deal have a fiduciary responsibility to consider the intangible impact of joining forces, and not just weigh up facts, figures, and balance sheets.

Regarding the LVMH/Gagosian rumor specifically, Stephens said that he has “never heard anything that would suggest LVMH is overly controlling or heavy-handed when it comes to the brands under its roof.” But the conglomerate’s treatment of Gagosian (or any other gallery) post-acquisition would go a long way toward determining the success or failure of merging the luxury and art worlds in this way. (By the way, a well-placed source relayed that Larry Gagosian still owns his business outright, meaning there would be no need for him to convince investors if he ever did decide to sell. A gallery spokesperson declined to comment.)

“If LVMH looked at Gagosian and said, ‘We believe in the trajectory of art as a category that justifies investment, and we believe [Gagosian] is well run with a strong executive and specialized knowledge that we don’t want to screw around with, and we want to make them… a distinct member of the family,’ that can work,” Stephens said. “But if it’s a matter of changing the management structure and value proposition, and tinkering with the core offering of this chain of galleries, then that could go awry.”

And the potential fallout for any gallery’s “core offering” in such a deal deserves more attention than it got during the initial hurricane of speculation over LVMH and Gagosian.

Anna Weyant in her studio, New York, 2022. Photo: courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

ARTIST’S CHOICE

Pop quiz: What’s generally the first and most important unknown that people in the art world try to puzzle through when a significant gallery closes or two notable dealers merge?

If you answered, “Where each of the artists is going to end up after the dust settles…” Congratulations, you’ve been paying attention to how this little carousel of ours turns.

For all its complications, there are certain ways in which the gallery business is as simple as it gets: If you don’t manage enough artists making enough work that buyers actually want to pay for, you’re dead. End of story. It would be an exaggeration to say that big-name dealers aren’t able to meaningfully increase demand for the artists they represent, but big-name dealers are more numerous and more interchangeable than they used to be. Now more than ever, star-caliber artists are the irreplaceable element.

And yet there was next to no discussion about artists’ possible resistance or defections when the unprecedented possibility of a major luxury brand acquiring a mega-gallery ricocheted around the art industry a few weeks ago. To me, that was a mystifying blind spot.

On one hand, I understand why so few people flinched. Fashion, luxury, and art have been getting increasingly frisky with each other, and we have every reason to believe that the attraction is only going to continue intensifying in the years ahead. A beloved artist’s estate can create a retail and licensing empire. Living artists can (and regularly do) link up with designers and fashion houses for limited-edition collaborations. High-end dealers do become romantically involved with movie stars and models. Apex-level collectors run gaudy private art foundations and fund major artists’ projects.

At the same time, for most artists, I think there is still a colossal difference between being able to opt into one-off fashion or luxury deals as a part of a larger studio practice, and having their entire artistic career managed by the subsidiary of a fashion/luxury-lifestyle company. And a subsidiary of a fashion/luxury-lifestyle company is exactly what Gagosian (or any gallery) would become if it were acquired by LVMH (or one of the brand’s rivals).

This isn’t to say that every single artist and estate on the gallery’s roster would mutiny. But I think a cross-industry acquisition like this would spark a lot of soul-searching for not only artists but for the partners, directors, and artist liaisons that would connect these practitioners to the executives at the very top of the corporate hierarchy.

Artist Titus Kaphar poses for a photograph with his artwork entitled ‘From Whence I came’ at Gagosian gallery in London on March 17, 2022. Photo: Justin Talls/AFP via Getty Images

Although art professionals sometimes discuss artists in terms uncomfortably close to how retail analysts discuss manufacturing equipment, artists are human beings with emotions, preferences, and (once they’ve amassed a certain audience) leverage in the marketplace. The same is true for gallery staff who are most directly responsible for keeping those artists content. Every one of these key stakeholders has options, and other high-end galleries would make damn sure that they knew it even before their current representative had finished selling the business to a luxury-lifestyle conglomerate.

All of which brings us back to the issue of risk. A multibillion-dollar company could never afford to close a deal for a major gallery without knowing for certain which artists and key staffers would remain after the ownership change. That means contracts (which so many artists hate). That means incentives. That means, in all likelihood, paying handsomely to ensure that the talent that matters most stays put.

Would money alone be enough? The luxury empire could try to sweeten the pot by producing many more artist-licensed collaborations while also restricting the pool of participating artists to those on the acquired gallery’s roster. I’m just not sure how much of a difference that would make. If an artist bristles at the idea of being represented by a company aligned with a luxury brand in the first place, you’re probably not going to win them over by offering even more opportunities to dive headlong into luxury brand-building.

This is why talent and personnel retention should be the first things people consider the next time the rumor mill kicks into hyperdrive: the “core offering” is the artwork, and this only comes from people with high-touch personalities and strong opinions who can’t be easily replaced if they don’t want to ride the art-meets-luxury trend lines into uncharted territory.

Still, that doesn’t mean tycoons from these sectors won’t try, or even succeed, in permanently joining forces eventually. From Stephens’s perspective, luxury retail may have an even greater incentive to push into the gallery sector than vice versa.

“What is considered to be luxury now is not what was considered to be luxury 30 or 40 years ago. The tectonic plates are shifting,” he said, citing the rise of streetwear as just one rupture to the old order. Plus, every fashion conglomerate “become[s] its own competition at some point. You’re operating so many brands within the portfolio that you hit a point of diminishing returns on profitability.”

Unless, that is, you start reaching into new sectors entirely. Going forward, a luxury lifestyle might encompass “everything from the champagne in your glass, to the hotel you’re spending the night in, to the luggage you brought with you, to the gallery you’re visiting today,” in Stephens’s words. In fact, we’re already there. But vertically integrating them all under the same corporate empire is tougher than the lifestyle makes it seem.

That’s all for this week. The Gray Market will be on hiatus for the Thanksgiving holiday next week. ‘Til next time, remember: just because it makes sense doesn’t mean it’s going to get done.