In the art world, a superstar artist quietly parting ways with his gallery of more than two decades is big news all by itself. But the fact that he did it on the eve of a major museum exhibition—that was genuinely eye-opening.

This is the case of Scottish-born artist Peter Doig, one of the most expensive of all living painters, who opened a hotly anticipated show of new paintings at the Courtauld Gallery in London last month.

There, Doig’s most recent works—12 new paintings and 20 works on paper—hang in a gallery adjacent to masterpieces by Van Gogh, Manet, and Gauguin. Not just any artist could hang in this company and still draw rave reviews. But he seems to have pulled it off: As Sotheby’s vice president and specialist Lucius Elliott put it to Artnet News, the Doig exhibition is “the most talked about show in London.” In our conversation, Elliott lauded him as a “brilliant and consistently inventive painter,” and even went so far as to suggest that it was the Gauguins which benefit from being near Doig’s work, and not the other way around.

Other market stakeholders would likely join Elliott in that opinion, given that just two of Gauguin’s paintings have sold for more than Doig’s £39.9 million auction record. At just 63, Doig still has a lot more time to supply the market.

Amid all the buzz about Doig’s artistic genius, it would have been easy to miss the major bit of industry news hiding in the wall labels: the conspicuous absence of Doig’s longtime dealer, Michael Werner Gallery. The paintings in the show appeared to have gone straight from Doig’s London studio, where he relocated in 2021 from his longtime home in Trinidad, to the museum.

Puzzled by the observation, we took it to Werner. Had dealer and artist parted ways after nearly a quarter of a century? A gallery spokesperson confirmed that they had.

Although Michael Werner gallery declined to comment further, Artnet News’s Annie Armstrong reported that Doig’s relationship with Werner began to deteriorate during the pandemic, and was hastened after the gallery decided to axe a financial arrangement it had with Doig’s wife Parinaz Mogadassi, who runs the London- and New York-based gallery Tramps. But details about what else might have caused their relationship to sour were scant.

We dug deeper. Among the twists and turns of Doig’s phenomenal market rise, we uncovered something of a cautionary tale about the pitfalls of the traditional gallery approach to navigating a runaway market. The Peter Doig story might even go some way towards explaining why increasing numbers of in-demand artists are looking for new models of representation today.

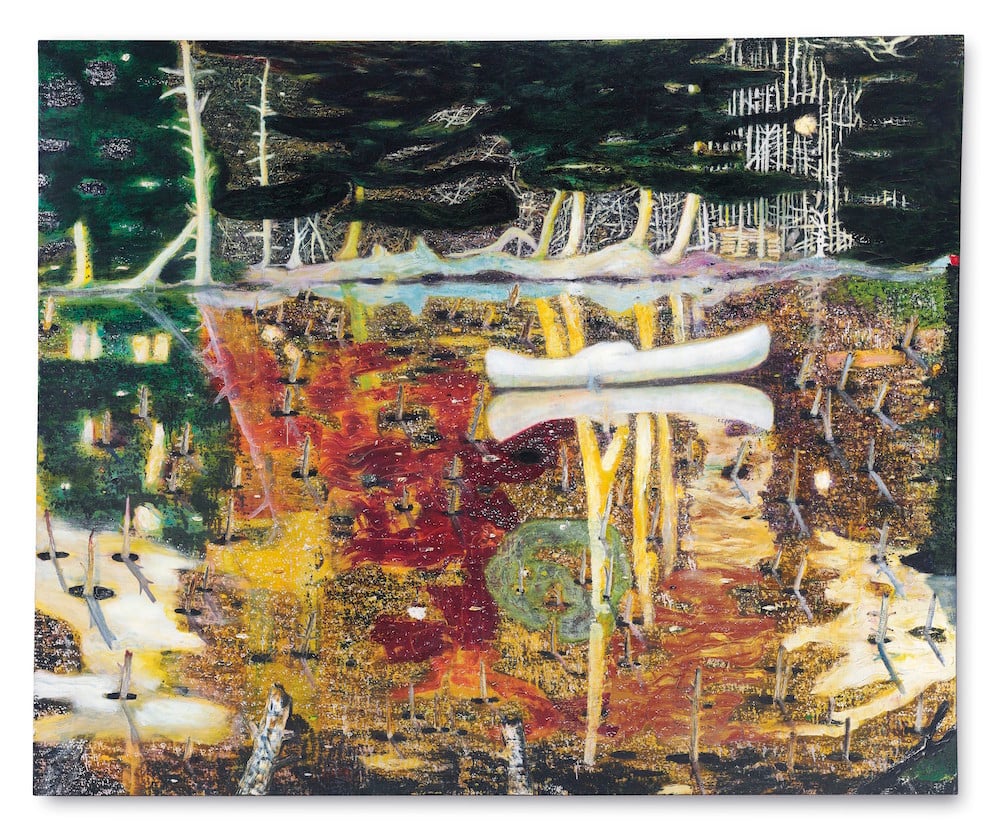

Peter Doig, Swamped (1990). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Doig’s Market Troubles

Doig’s fraught relationship with the art industry began early on in his career.

At art school, he was not making work that was popular with buyers. He was dubbed a “terrible draughtsman” by a fellow student at London’s prestigious Central St. Martin’s College. At his graduation show at Chelsea, in September 1990, his paintings were priced at £1,000 each “and nobody bought one,” per a 2017 profile in the New Yorker.

All that began to change in the early 2000s, when Doig’s work, already represented by taste-making gallerists Victoria Miro, Gavin Brown, and Bruno Brunett (of Contemporary Fine Arts in Berlin), began to filter onto the secondary market.

His debut at an auction house evening sale was at Sotheby’s in 2002, the same year the artist moved from London to Trinidad. As auction veteran and private dealer Francis Outred recalled, “putting Peter into an evening auction was a big step at a time when not many young artists were being presented in that way.” Some ten interested parties competed to drive up the price of Swamped (1990) to £322,500, “which was a massive price for a young artist at the time,” Outred said.

If that price seemed steep then, it certainly didn’t by the time the same painting was flipped in 2015 for $25.9 million—and then again for $39.9 million in 2021. (According to sources, it eventually landed with a determined Asian billionaire who had made it clear he would go to any length to get it if it became available on the market again.)

It was around that first market spike in 2007 that Doig caught the attention of notorious market speculator Charles Saatchi.

Blocked from buying Doig’s paintings directly from his dealers, who worried that he would resell them, Saatchi circumvented the galleries and bought several artworks on the secondary market at what were then believed to be highly inflated prices. He later sold several of these works to Sotheby’s. In 2007, one of them, White Canoe, was auctioned for $11.3 million, smashing the high $2.3 million estimate. Doig received no proceeds from that auction sale.

Speaking to the New Yorker a decade later, Doig, who declined to be interviewed for this article, said the price hike “definitely slowed me down.” By this point, he was gaining institutional recognition, with a major Tate exhibition in 2008, and he said the flashy market event transformed how people perceived his work. “You get seen as a different kind of artist, one whose work is of interest only to the mega-rich,” he told the New Yorker.

Doig’s primary market prices climbed in tandem with his auction market. At the time of the initial spike in the mid-late aughts, large paintings were selling privately for under £100,000; in 2013 prices had ballooned to between $300,000 and $3 million, according to the New York Times. And by the time Doig parted ways with Werner, sales for primary market paintings were in the high seven figures, according to sources familiar with the market.

Doig’s relationship with Victoria Miro cooled after he moved to Trinidad, and they officially stopped working together in 2008. His other two galleries were squeezed out after Michael Werner assumed exclusive representation in 2012. But his early dealers’ tight-fisted approach to his primary market continued with dealer Gordon VeneKlasen, who is a co-owner of Michael Werner and worked closely with the artist for decades. VeneKlasen, who declined to comment for this story, kept Doig’s work out of art fairs, and sold only to carefully selected buyers.

Depending on whose interests are being considered, you could say this strategy backfired. The harder Doig’s work became to access on the primary market—and its scarcity was also down to the fact that Doig produces slowly, some years releasing nothing at all from the studio—the more desirable the works became on the secondary market, tempting even the most carefully selected collectors.

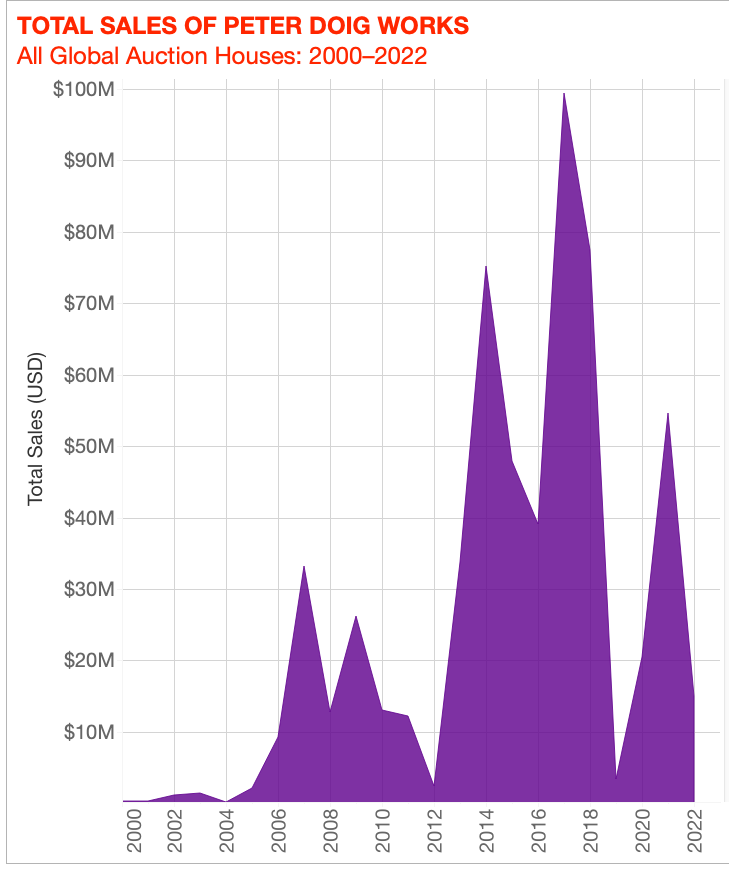

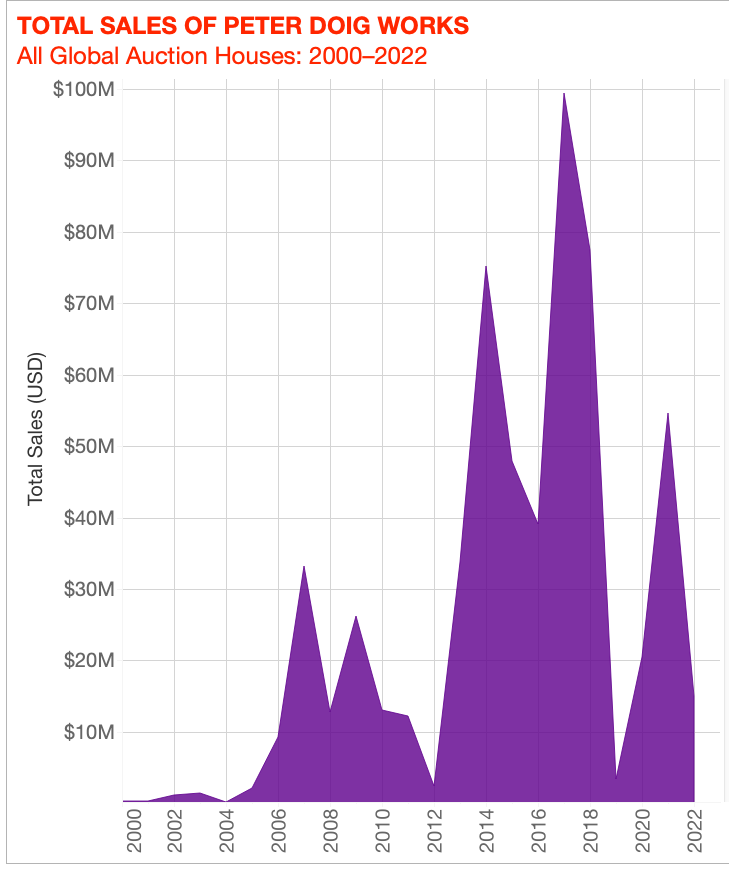

© Artnet Analytics.

The sharp peaks and valleys of Doig’s total sales at auction reflect the scarcity of the work to the public auction market, though Artnet News understands more have been traded privately. Few major paintings ever hit the auction block, and virtually no post-2000 large-scale works have ever come to market. His records are all for 1990s works.

So Doig’s stratospheric auction totals are mainly attributed to two classic market phenomena: speculation and scarcity. However, others we spoke to suggested a third factor at play. A major auction spike can be seen in Doig’s market around 2017 and 2018. In 2017, total sales reached nearly $100 million and he made his then-record $28.8 million price. So what happened?

“This market at auction seemed strange for a long time, as if there were a small group of buyers—possibly a Russian consortium—paying the insane prices achieved at auction,” said art advisor Todd Levin. “This situation was particularly apparent because almost all Doig’s paintings were consistently selling to either the reserve guarantor, or at one bid above low estimate.”

Levin added: “There was never a bidding war for these paintings in the auction room. At this price point there was only one entity bidding, possibly two at most. It was clear that the market was being gamed somehow.”

Sources said the now-sanctioned Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich was the buyer of Reflections (What does your soul look like?) (1996) which sold at Christie’s in 2009, for $10 million. A fellow top collector is Ukrainian Victor Pinchuk, another oligarch whose pipe and steel company was doing significant business with Russia’s biggest oil companies and relied heavily on the Russian market. Pinchuk was reportedly the buyer of White Canoe at the 2007 Sotheby’s London sale. Pinchuk also owns (or did own at one point) two other large-scale Doigs: Country Rock Version (2001-02) and Country Rock (1998-99), as Judd Tully reported in 2014.

Not everyone agrees with Levin’s theory. Some insist that these buyers were all bona fide collectors, even if they did end up selling on the work eventually (as sources indicate Abramovich did with Reflections, selling it privately to Steve Cohen.)

Outred, who has placed the most Doig works privately, said he has observed “broad interest from collectors” ever since the late ‘90s, with interest expanding geographically to the east from the early ’00s. “There were always multiple potential buyers for each work I have handled,” he said, adding that he recalled multiple bidders at public sales too. “At each stage, the commentators have questioned the values attached to Peter’s works, but the fact is that his work doesn’t just appeal to one or two wealthy collectors. It probably has a greater breadth of collecting interest than any other living artist in the market today.”

Others who dismissed the notion of a consortium pointed out a direct correlation between increased market activity and critically acclaimed institutional shows in that period (at Tate in 2008, Fondation Beyeler in 2014, and the Louisiana Museum in 2015).

A viewer admires Canal (2023), one of the most recent paintings by Peter Doig in his self-titled exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery in London. Photo: Vivienne Chow.

So What’s Next for Doig’s Market?

After all this chaos, it is little wonder that Peter Doig might have been questioning his existing relationship with his gallery, whose main job is to help build an artist’s legacy through exhibitions and scholarship, while protecting them from any market interference that may damage or distract from said legacy.

Though the decision to part ways with Werner might have been hastened by its treatment of his wife, a source familiar with the situation said the artist himself had already begun to question the dynamics of his relationship with the gallery and its public-facing representation of him.

Whatever happened between Werner and Doig, the news of their split undoubtedly has galleries all over the world dusting off their dancing shoes, preparing their courtship in the hope of securing representation of one of most sought-after artists of our time. But as it turns out, they might be out of luck, as Doig does not appear to be looking for a new gallery at all.

Tramps’s Mogadassi confirmed to Artnet News that “the most recent work is still with the artist,” adding that Doig is opting to hold onto more works moving forward since it makes exhibition planning “far easier.” Indeed, one of the perils of secondary market activity is that artists often lose track of their works, making it even trickier to secure loans for exhibitions. “The ability to make cohesive and poignant institutional shows remains a chief concern for a living artist, and being able to ensure that he has access to key works at critical times remains a priority,” Mogadassi said, adding that her own gallery will continue to collaborate with Doig on projects as it has done in the past.

Jean-Paul Engelen, president, Americas for Phillips auction house tends to agree. “I feel that artists have a choice—do you want to be in the Metropolitan [Museum of Art]? Or do you want to produce for a beach house? Doig to me seems to fall into the category of ‘he’s going to the Metropolitan.'”

While some feel that Doig’s market conundrum might be resolved by securing a better gallery, the artist seems to be taking a different tack, similar to a growing tide of artists discontented with the restrictions that come with traditional gallery representation, which decides what they show, where they show it, and who they sell to (while taking half of all sales).

As a result, a growing number of successful artists have been abandoning exclusive relationships with their galleries (see: Jeff Koons, Richard Prince, Nicolas Party). Others negotiate a “hall pass to sell occasionally from the studio,” according to art advisor Lisa Schiff, or a different commission split. And increasingly, artists are opting to forego the traditional model altogether, whether that is for alternative models such as an agency, or, as Doig seems to be doing, deciding to go it alone.

“Why should any artist relinquish the unequivocal sense of autonomy that the act of making art allows by binding themselves to the antiquated notions of ownership and servitude the representational model in many ways perpetuates? There is no ‘art world’ without art and the artists who make it,” said Mogadassi. “An artist who wants to set the pace and conversations surrounding their own work, shouldn’t be scrutinized and intimidated, but rather should be respected and encouraged. It is the most intuitive and obvious way forward.”

While Doig holds close to his museum pieces, he has been experimenting with different models of marketing his work. He has retained the services of secretive art world power attorney Joe Hage as his legal counsel, and through Hage’s Heni publishing venture, sold a limited edition series of six prints based on original snowscape paintings. All 250 editions of each of the six prints, priced at $3,000, sold out. Doig will create future prints with Heni, a source confirmed, though they also stressed that does not mean Hage “is holding the reins in any sort of way.”

Stakeholders in the traditional art industry may feel dismayed by this turn of events. Others are convinced it cannot work. Even as there is an emphasis on placing works in institutional collections, market observers point out that you do need a certain amount of objects to circulate at sensible prices in order to maintain a market. “To maintain a healthy balance of market supply vs. demand one can’t place all primary works directly into museums, permanently removing them from circulation,” said Levin. “Peter’s market would benefit from a major gallery assisting him in putting his market in order for the longer term.”

But the Doig camp is committed to writing his own legacy from now on. And while the market may be a secondary consideration to his bid for autonomy, Mogadassi said we can rest assured: “In terms of the primary market—the interest and demand in his works remains unwavering.”