The Back Room

The Back Room: Billions and Billions Served

This week in the Back Room: Billionaires give and take, Banksy prints go berserk, bidders chase youth, and much more.

This week in the Back Room: Billionaires give and take, Banksy prints go berserk, bidders chase youth, and much more.

Tim Schneider

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy.

This week in the Back Room: Billionaires give and take, Banksy prints go berserk, bidders chase youth, and much more—all in a 7-minute read (1,913 words).

__________________________________________________________________________________

MacKenzie Bezos attends the SEAN PENN J/P HRO GALA: A Gala Dinner to Benefit J/P Haitian Relief Organization and a Coalition of Disaster Relief Organizations at Milk Studios on January 6, 2018 in Los Angeles, California. Photo: Greg Doherty/Patrick McMullan via Getty Images.

Today, most people tend to view every fortune of a billion dollars or more like telepathy or the ability to fly: whether its owner is a superhero or supervillain all depends on how they use it.

This is especially true in the U.S. (and increasingly, U.K. and E.U.) art industries, where a steady decline in public funding has handed mega-philanthropy a vital role in sustaining nonprofit institutions.

This principle was reinforced on Wednesday, when MacKenzie Scott, the novelist and philanthropist formerly known as Ms. Jeff Bezos, announced she was doling out $2.7 billion in unrestricted donations to 286 organizations across the country—including many affiliated with the arts, such as the Studio Museum in Harlem, the New England Foundation for the Arts, and United States Artists.

__________________________________________________________________________________

But is the promise of “Good Billionaires” like Scott actually hurting art and culture?

That’s the question I worked through thanks to journalist and author Anand Giridharadas’s incineration of beloved plutocrat Warren Buffett last weekend. And I think the answer is yes, on both the nonprofit and for-profit sides.

What provoked Giridharadas was a bombshell ProPublica investigation showing that America’s very wealthiest—even mega-philanthropists like Buffett, Michael Bloomberg, and Bill Gates—have been legally exploiting the tax code in a unique way to pay next to (and sometimes literally!) nothing to Uncle Sam.

Mega-philanthropy has been the best camouflage for the damage, Giridharadas argues. What makes donations from “supposed Good Billionaires” more insidious than donations made by “the crooks and the scoundrels and the people manifestly looking for quick P.R. highs” is that they give so much more—and their public images are so much cleaner.

For instance, the late mega-collector/mega-donor Eli Broad wasn’t always the philanthropic angel he was often portrayed as. Carolina Miranda of the L.A. Times noted that he may have stuck LACMA with $5.5 million in additional construction costs on a building he otherwise financed on its campus (a Broad spox denied it), refused to endow that building for upkeep, and of course ultimately kept his collection to open his own museum.

The grand irony is that mega-donations from the Broads and Scotts of the world have become so important to art institutions partly because the U.S. is sacrificing trillions of dollars in tax revenue (see: potential public funding) to enrich the billionaires signing those fat philanthropic checks.

__________________________________________________________________________________

The Good Billionaire myth is hurting the art market, too. Why have the middle-class collectors who once sustained a more equitable version of the industry become an endangered species? Partly because the costs of simply getting by, let alone getting far enough ahead to acquire artwork, have risen so much.

According to Bloomberg, the cost of college and the median home price in the U.S. are each about 50 percent higher for millennials than they were for boomers, yet millennial wages are up only 20 percent. Full-time employment and robust benefits (pensions, healthcare, paid family leave) have become vanishingly rare too. Public programs are not well funded enough to pick up the slack.

And part of this has been enabled by the narrative that the superrich will take care of the rest of us, including when it comes to art and cultural spending. Even though some deserving folks occasionally win the Good Billionaire lottery, it’s a losing trade most of the time.

__________________________________________________________________________________

I sincerely think MacKenzie Scott is trying to help nonprofits with her wealth. But her would-be remedy is only treating a symptom, not the illness—namely, the tax system that enabled her ex and his billionaire peers to build their fortunes. Until or unless that system is reformed, prepare for the institutional sector and the art market to become even more grossly polarized than they already are.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Banksy, White Idiots, or maybe it’s called Idiots (White), who can really say these days. Courtesy Burnt Banksy’s Twitter account.

You can get the god’s eye view of Banksy’s prints market in three annual auction-sales totals:

Whether that growth qualifies as robust or cancerous depends on your perspective. What’s undeniable from Eileen Kinsella’s deep dive is that the street-art legend’s editions market has transformed in multiple ways over the past 10 years.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Around 2002, Banksy released his first commercial prints through multiple print galleries: primarily Tom Tom (which later became Art Republic) and Pictures on Walls, run by Banksy’s longtime right-hand man Steve Lazarides. (The two have since split. Sources say it wasn’t pretty.)

Prices were around £200 to £300 each. Editions rarely came with certificates of authenticity (COA). Sometimes buyers didn’t even get a receipt!

Fun Fact: “Some dealers would pay 50 students £50 each to be in the queue with a bonus if they got something.” —Brian Balfour-Oatts of London dealership Archeus/Post-Modern.

__________________________________________________________________________________

In 2007, total auction sales of Banksy prints leaped 10x year-over-year, from about $127,000 in 2006 to $1.3 million.

The next year Banksy launched Pest Control to authenticate his works and police fakes. After 2009, every genuine Banksy came with a Pest Control COA. The outfit can retroactively issue certificates for works made before its founding too.

The artist also took more control of his primary-market sales, sometimes offering works through random lotteries. Fun Fact: In 2010, Banksy directly offered a now-popular print, Choose Your Weapon, showing a figure in a hooded sweatshirt walking a Keith Haring-style dog. After the hours-long line got hooligan-ish, he released a supplemental “queue jumping” edition for the fans who were boxed out.

__________________________________________________________________________________

It’s wild! Mainly for three reasons:

Since Banksy has not run a random lottery for some time, demand can only be fulfilled through auctions and resale dealers. Christie’s and Sotheby’s now each hold two dedicated Banksy print sales per year, “many of which have been 100 percent sold,” Eileen writes.

Balfour-Oatts relays that “some of the mega-galleries handle Banksy works quite often, but are very coy about saying so.”

No wonder Pest Control is inundated with requests—and sometimes slow-walks COA issuance for recent prints to combat flippers. This has led some Banksy collectors (and even smaller auction houses) to trade prints with the promise of a COA to follow—which is not normal! (Other evidence of authenticity, such as emails trails, are often substituted, but still…)

Fun Fact: This March, one of the queue jumping editions of Choose Your Weapon sold at Sotheby’s for £201,600. So don’t expect this rocket ship to run out of fuel anytime soon.

__________________________________________________________________________________

© Artnet Analytics 2021.

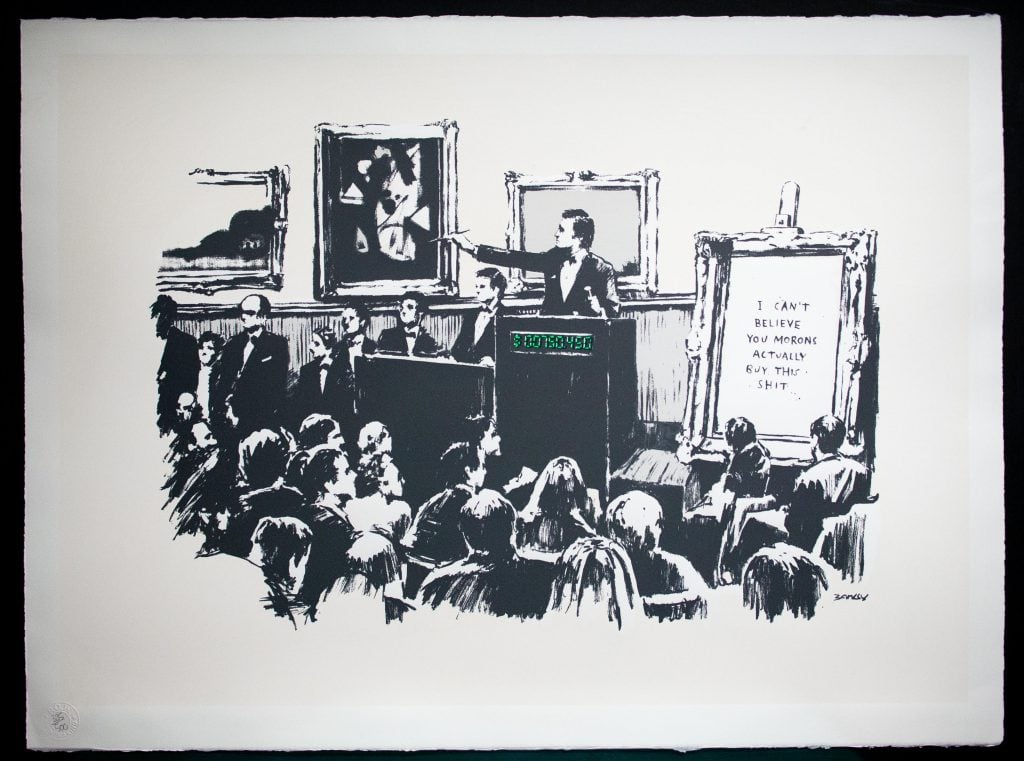

If you’ve ever laid awake at night wondering how genre-by-genre auction sales in May fared before, during, and after COVID, today is your lucky day. (Also, may I recommend considering a spa vacation, or at least switching to herbal tea after lunch?)

With the return of the traditional slate of premier May auctions in New York, it’s no surprise this year’s biggest resurgences were in the Impressionist-Modern and postwar-contemporary categories. (We define these by artist’s birthdates: Imp-Mod covers artists born from 1821 through 1910, and P.W.C. covers artists born from 1911 through 1974.)

But the most interesting story in the data is the pronounced shift toward youth over the past two years. While Imp-Mod sales came in more than $322 million lower (about 25 percent) this May compared to the same month in 2019, postwar and contemporary sales were down a mere $76 million (roughly six percent) in the same face-off.

P.W.C. works also outsold Imp-Mod works by more than $162 million this May, flipping the script from the 2019 May sales. Sales of ultra-contemporary works (made by artists born in 1975 or later) ascended almost 250 percent over this two-year span, from $35.7 million to $86.2 million last month.

Look for the push toward present-day talent to continue as the market keeps gathering strength in the months ahead.

__________________________________________________________________________________

“What does every rich and famous person want more than anything? Relevancy… You have a Warhol Marilyn? Cool, we know you’re rich. But if you have, say, Christina Quarles, you’re of our time.”

—Anonymous dealer on the allure of the young artists being added by mega-galleries. (For details, check Nate Freeman on Gagosian’s farm team.)

__________________________________________________________________________________

LiveArt Market, ex-Sotheby’s dealmaker Adam Chinn’s peer-to-peer platform enabling buyers and sellers to transact anonymously, went live by invitation. Anna Brady unpacked how it works. (The Art Newspaper)

__________________________________________________________________________________

Can Paris unseat London as the top Euro art market? Melanie Gerlis dons a beret to investigate. (ARTnews)

__________________________________________________________________________________

London Gallery Weekend was a “smashing success” but will it kill off art fairs? (Artnet News Pro)

__________________________________________________________________________________

The Robert Indiana estate reached a settlement with its biggest backer after three years of legal hell. (Artnet News)

__________________________________________________________________________________

Here’s what made a mark in the latest Wet Paint (and elsewhere).

Skarstedt will open a Paris gallery (and poached Maria Cifuentes from Phillips Paris to run it.)

Cady Noland secretly installed her first new work in decades at Galerie Buchholz in NYC.

The Nasher Museum at Duke University acquired a painting by Korakrit Arunanondchai.

Julian Schnabel will be the subject of the Brant Foundation’s September show.

McArthur Binion is now represented by Xavier Hufkens, with his first solo exhibition at the gallery set for fall 2022. (Binion will also continue working with Lehmann Maupin, Massimo De Carlo, and Richard Gray.)

Ashley Bickerton joined the stable of Various Small Fires.

Blum & Poe added ceramicist Kazunori Hamana to its roster and will solo-show him in L.A. this September.

NYC’s Company Gallery now reps the Women’s History Museum collective founded by Mattie Barringer and Amanda McGowan.

Christie’s will open pop-up spaces in Southampton (this month) and Aspen (July 3).

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gio Swaby, Love Letter 5 (2021). Photo courtesy of Claire Oliver Gallery, New York.

__________________________________________________________________________________

Date: 2021

Seller: Claire Oliver Gallery

Price Range: $25,000 to $50,000

Acquired By: The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

__________________________________________________________________________________

Gio Swaby is on a trajectory unimaginable to the art market a generation ago. A 29 year-old interdisciplinary artist hailing from the Bahamas, she is still in the midst of her M.F.A. studies at Toronto’s Ontario College of Art and Design University. Yet she joined the roster of Harlem’s Claire Oliver Gallery last year without ever meeting the dealer—after curator Danielle Krysa brokered an introduction via Instagram. Her inaugural solo exhibition at Oliver’s space was arranged remotely during the shutdown.

That exhibition, “Gio Swaby: Both Sides of the Sun,” celebrated Black womanhood through threaded-line portraits and silhouettes where textile patterns echoed the models’ natural curves. It also sold out before the end of its run on June 5. Private buyers included author Roxane Gay and actor Hill Harper, and Swaby’s waiting list now swells beyond 100 names.

More impressively, eight institutions acquired work (pending final board approval). A gallery spokesperson confirmed that one of those eight, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, even reworked its upcoming exhibition “Fabric of A Nation” to include Love Letter 5, which it officially acquired this week. Just imagine what Swaby can do now that she can meet people in person again.

__________________________________________________________________________________