The Back Room

The Back Room: Tiny Slices of Art, Big Business

This week: Fractionalized art ownership, David Zwirner loses a star, a Venetian Monet, and much more.

This week: Fractionalized art ownership, David Zwirner loses a star, a Venetian Monet, and much more.

Naomi Rea

Every Friday, Artnet News Pro members get exclusive access to the Back Room, our lively recap funneling only the week’s must-know intel into a nimble read you’ll actually enjoy. This week, Artnet News European market editor Naomi Rea steps in for your usual scribe,Tim Schneider.

This week in the Back Room: Fractionalized art ownership, David Zwirner loses a star, a Venetian Monet, and much more—all in an 8-minute read (2,336 words).

__________________________________________________________________________

Pablo Picasso, Fillette au béret (1964). Photo by Seraina Wirz / © Succession Picasso / 2021, ProLitteris, Zürich.

Artnet’s Spring 2022 Intelligence Report, out in just over a week, will examine what happens when the art market tries to become the stock market. The longstanding conversation about art becoming an asset class accelerated during the pandemic, and Katya Kazakina took a deep dive into the end game of this trend: fractionalized art ownership, a model that lets people invest in shares of an artwork and benefit from a portion of the upside when the work is eventually sold.

While you wait for the full story on the rise of this phenomenon (and trust us, you’ll want to come along for the ride), here is a sneak preview of the dynamics at play.

Last year, the Swiss bank Sygnum attracted more than 60 investors to 4,000 shares of a 1964 painting by Pablo Picasso, Fillette au béret, with each share valued at CHF1,000 ($1,070).

The painting, bought for $3 million in 2016, was listed at CHF4 million ($4.3 million), with investors essentially buying the owner out for a 38 percent profit. But the company gains even more with a onetime management fee of 8.9 percent of the original purchase price, or $89 per token. And if the company sells the painting within five to eight years, it will make an additional 2.5 percent commission.

Meanwhile, the fast-growing fractional art ownership company Masterworks bought about 65 works of art to the tune of more than $300 million last year.

Masterworks adds a roughly 11 percent fee to the purchase price and then offers these works like IPOs, effectively flipping them to investors. The company charges a 1.5 percent annual management fee and earns 20 percent of any profit realized when the works are sold.

The target audience for these schemes is retail investors looking to get rich quick, and the emerging wealth sector—often those enjoying newfound crypto largesse—as opposed to old money or hedge-fund and real-estate millionaires. Those deep pockets can afford to buy artworks outright.

__________________________________________________________________________

Both Sygnum and Masterworks have ambitions to scale up, with the Swiss bank pitching tokenized artworks to conservative money managers and banks, and Masterworks reportedly approaching major investment banks about adding fractional art to their diversified offerings to clients.

But without a solid track record or traders with the requisite art-market expertise, fractional art sales are likely to remain a hard sell to large financial institutions.

For now, these schemes are most attractive to a mass audience interested in buying into a formerly inaccessible market and spinning a profit. To some, it may sound like a Robin Hood scenario, but it’s important to ask: who is actually winning? With large financial institutions still out of the game, these companies depend on the buy-in of the (relatively) little guy, who could conceivably be making a smarter investment choice. So why aren’t these vital investors demanding a larger slice of the upside?

____________________________________________________________________________

Harold Ancart, left, at the opening of “Freeze” (2018). Photo by Justyna Fedec courtesy David Zwirner.

In the latest Wet Paint, we learned that the Belgian painter of moody landscapes, Harold Ancart, has parted ways with mega-gallery David Zwirner, which launched his ascendant star back in 2018.

Meanwhile, if you were thinking something was rotten in the state of New York the other day, that might be because an anonymous art duo unleashed a stink bomb at the VIP opening of the Whitney Biennial to ruffle the feathers (and wrinkle the noses) of the downtown establishment.

Here’s what else made a mark around the industry since last Friday morning…

Art Fairs

Auction Houses

Galleries

Institutions

NFTs and More

____________________________________________________________________________

© 2022 Artnet Worldwide Corporation.

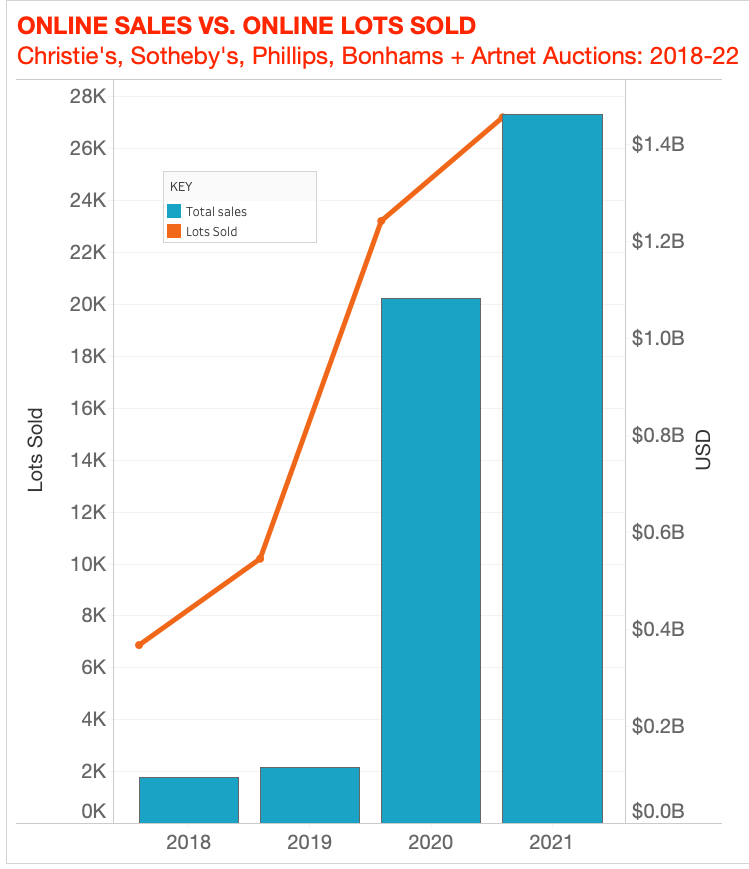

It’s no secret that the pandemic made buyers, sellers, and auction houses all more comfortable with the idea of transacting online.

Two years post-lockdown, many in-person art events and auctions have returned. Are people still buying as much art online? Julia Halperin investigated.

For the full download, including which of the Big Three houses is the reigning champ in the online space, click through below.

____________________________________________________________________________

“I know this is shocking, but this project is coming to an end. I never intended to keep the project going, and I don’t have a plan for anything in the future.”

—Discord user Jakefiftyeight, aka Ethan Vinh Nguyen, on pulling the rug out from under investors in Frosties, the NFT collection he launched with Andre Marcus Quiddaoen Llacuna. Less than an hour after their 8,888 ice cream cartoon characters sold out, they transferred $1.1 million in proceeds to their own crypto wallets and shut down the project. They’ve since been arrested on charges of conspiracy to commit wire fraud and money laundering. (Artnet News)

____________________________________________________________________________

Claude Monet, Le Grand Canal et Santa Maria della Salute (1908). Courtesy Sotheby’s.

____________________________________________________________________________

Estimate: In the region of $50 million

Selling at: Sotheby’s Modern Evening Auction in New York

Sale Date: May 17

With the art world’s eyes trained on Venice ahead of the Biennale, what better time to offer a prize Monet vista of the city? The artist only visited La Serenissima once—though he was prolific during the three months he was there, capturing the city in 37 paintings, among them this luminescent depiction of the grand canal with the Santa Maria della Salute church in the background.

Sotheby’s says its hefty estimate is in line with the $50.8 million result achieved for Monet’s 1918 Coin du bassin aux nymphéas at the house last November, or the $70.4 million netted by Le Bassin aux nymphéas (1917–19) in May 2021.

While Le Grand Canal may be the most expensive, it is not the only Monet appearing in the house’s marquee May sales in New York. The artist’s Les Demoiselles de Giverny (1894), consigned by Washington Commanders owner Dan Snyder, is also being offered stateside after an eleventh-hour withdrawal from the house’s spring sale in London. The results of that evening, marketed by the house as “raining Monet,” don’t bode particularly well. Snyder’s four other Monets drew tepid prices; one failed to sell entirely.

A striking water lily painting consigned by the family of a Japanese collector did fetch an above-estimate £23.2 million in London, which proves that good examples—particularly of the water lily motif—are still attracting demand. But the fuller picture suggests that, much like the acqua alta posing a perennial threat to Venice, the market could be a little flooded with Monet.

____________________________________________________________________________