Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, asking the post-pandemic art industry the uncomfortable question, “Is this it?”

INSTANT REPLAY

Despite the many tragedies COVID-19 caused last year, the silver lining to the once-in-a-century upheaval was supposed to be that it would spark a radical rethinking of life, politics, culture, and business. More to the point, the pandemic was supposed to empower anyone who could deliver actual solutions when we needed them most.

But to paraphrase funk legend Rick James in the Chappelle’s Show sketch that defined an era of comedy for old millennials, inertia is a hell of a drug.

I would be lying if I said this proved true everywhere in the U.S. Operation Warp Speed developed not one but three phenomenally effective COVID-19 vaccines in under a year—less than a quarter of the four years needed to produce the measles vaccine, previously the fastest-developed jab in medical history. Congress passed (by the thinnest of margins) the largest, most progressive stimulus and social-welfare package in a generation, and it looks poised to do the same for a significant bipartisan infrastructure bill currently speeding toward a vote. Across industries, a subset of businesses has also scrapped caution to bear hug maverick strategies their executives would likely have considered reckless as recently as late 2019.

But close to 18 months since COVID made landfall in the U.S., and nearly five months since vaccines became widely available in New York and several other states, I think it’s time to stop pretending the art market responded to this epic challenge with sufficient creativity and vision for the long term.

Even (perhaps especially) at the very top of the hierarchy, where the resources necessary for transformation are most abundant, it looks like most players are much more interested in re-establishing the status quo with bare-minimum tweaks, than in using the crisis to transform themselves into a shape fit for the third decade of the 21st century.

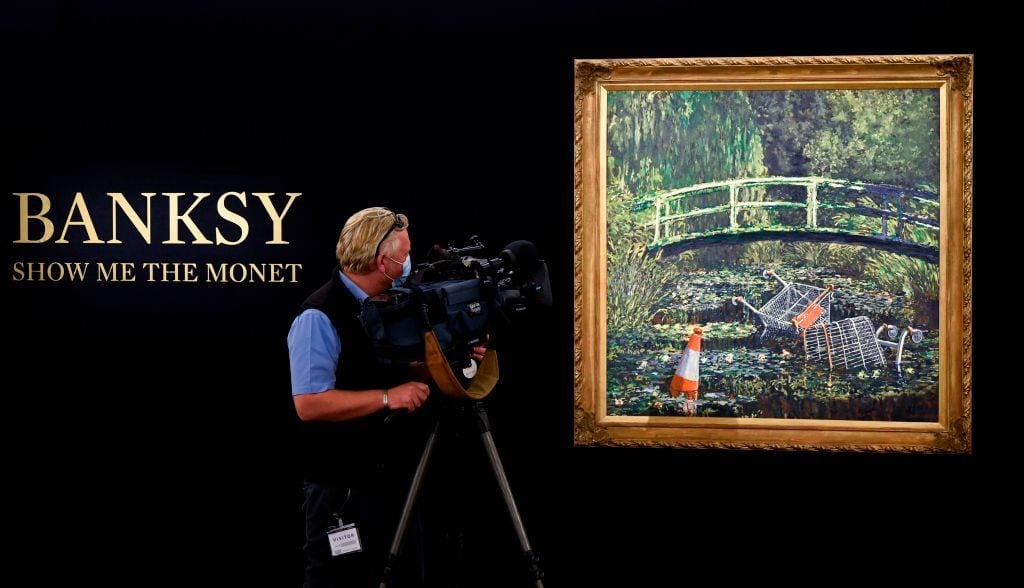

Right now I can only conjure two initiatives that have even the vaguest scent of a moonshot: Art Basel Hong Kong’s experiment with interactive holograms, in which the fair beamed in select dealers from a small assortment of international locations for brief remote pitches with a handful of V.I.P.s.; and Pace’s experiential, ticket-sales-centric Superblue offshoot. I’m not even sure I should include the latter here, since Superblue was already deep in development before anyone outside a lab, hospital, or medical school heard the phrase “novel coronavirus.” But I’m so starved for other reference points that it gets the benefit of the doubt.

Beyond these scant exceptions, the most significant change across the for-profit art trade has been simply to hold more sales of more stuff more often, via technology that has basically been available for at least five to 10 years.

Auctioneer Oliver Barker holding court over Sotheby’s global e-auctions in July 2020. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Major auction houses have improved their live-streaming capabilities and “disrupted the traditional calendar” by holding the maximum number of sales that consignments will allow. Among mega-galleries, Gagosian Premieres is more a triumph of booking than of innovation; the initiative boils down to live-streaming brief concerts and short interviews with artists from inside their current exhibitions. The primary technological achievement of David Zwirner’s much-discussed Platform project has been to funnel more galleries from more cities into a lightly refined version of the grid-based, click-to-buy e-commerce template we use to cop toothbrushes from Amazon and lunch from Chipotle.

Then there are the art fairs, whose most prevalent advances so far are online viewing rooms (see above comments on Platform), tolerance for downsizing the number of exhibitors at live events, and onsite temps to man “ghost booths” with art sent in from overseas.

I can hear some of you shouting from the back: But what about the industry’s sudden-onset interest in NFTs and cryptocurrency? No slight to anyone working in that field, but I would argue that NFTs are by and large being treated by galleries and auction houses as just another S.K.U. (retail parlance for “stock keeping unit,” meaning a distinct type of good or service) to flog in more or less the same ways as every other work in their respective holdings.

Yes, NFTs draw a new segment of the world’s wealthy into the collecting fold and make a new segment of artists into viable commercial propositions. Yes, they raise new questions about governance and custodianship after a sale. Yes, they have long-term potential to alter the market in more fundamental ways.

But as of mid-August 2021, they aren’t yet moving auction houses, dealers, or fairs to meaningfully alter either the average buyer’s experience of art, nor its laborious sales process. Aside from the cash their sales have pumped into the system, the biggest benefit of NFTs to traditional art sellers has been to obscure how little else in the trade evolved during our year in COVID.

All of which is to say that, on the selling side of the industry, the main response to the pandemic seems to be to major in the minor. Is this really the best we can do?

THE QUICK AND THE DEAD

Aside from general frustration with societal inertia, the primary reason I’m thinking about all this is that I just finished futurist Doug Stephens’s latest book, Resurrecting Retail: The Future of Business in a Post-Pandemic World.

Although I don’t think every concept in his book fits snugly within the unique silhouette of the art trade, several do. More importantly, its second half bulges with case studies of sellers throughout the commercial hierarchy taking big swings at transformational change. In comparison, the modest moves made by art sellers end up looking even quainter.

The core thesis of Resurrecting Retail is simple but powerful. Contrary to the popular idea that COVID merely accelerated pre-existing trends in life and business, Stephens argues that the pandemic plunged us all through a metaphorical worm hole into a universe that would not have existed otherwise. Yes, retailers’ old problems worsened at what often proved to be breakneck speed. But the crisis also reshuffled the average person’s priorities in ways that only the epochal calamity of a lingering global plague can. The only proper response for any business, he writes, is to look in the mirror and be ready to reshape itself from skeleton to skin.

The business side of the art world has an unusual tendency to luxuriate in a largely unearned reputation for lateral thinking, but it is not alone in mostly underreacting to the pandemic—at least based on what Stephens told me when I asked him whether the general retail sphere has stepped up to the challenge.

“What I’m seeing is sort of a classic bell-curving of strategic behavior,” he said. “The bottom 10 to 20 percent of retailers have taken nothing from the crisis and have essentially tried to ride it out. Many have failed. The top 10 to 20 percent, like Nike for example… either already made the strategic choices necessary to accelerate through the pandemic, or used it as a springboard into new methods, convoys, and tactics. And, finally the remaining masses have, to varying degrees, made the operational changes [necessary] to allow them to survive.”

Some members of this last group may emerge from the crisis more resilient than when they entered it, Stephens said. But others would not. That doesn’t necessarily mean they’ll drown in the next few months or even the next few years. It does mean, however, that treading water will probably continue to get a little harder for them every day, until they finally sink below the waves for good sometime in the future.

This is why I think the worst outcome for the long-term health of auction houses, galleries, and fairs is that so many of them have managed to keep selling just enough (or more) to get by for the past 18 months after making only minor-to-modest adjustments.

Since COVID has not proven to be a mass-bankruptcy event 18 months in, too many people have been able to convince themselves that the mostly familiar business model must not be that shaky. Problem is, this is classic boiling-the-frog thinking: everything seems fine, until the moment it’s too late.

Yayoi Kusama, INFINITY MIRRORED ROOM: LET’S SURVIVE FOREVER (2017) at the wndr museum. Photo courtesy of the wndr museum.

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

The greatest value of Stephens’s book is in its short case studies and the framework he builds around them. He segments the retail sphere into 10 “archetypes,” each of which serves a viable-enough purpose to give its adherents a fighting chance against endlessly better-resourced behemoths like Alibaba, Amazon, Chinese superstore JD.com, and Walmart. For Stephens, every one of these archetypes is a viable reply to what he sees as the existential dilemma facing every business in 2021: “If your brand is the answer, what’s the question?”

More often than not, it’s a mistake to try to graft entrepreneurial specifics from other industries directly onto the art business. There are too many quirks and not enough scalability for most to apply. (I’m guilty of misjudging the line myself sometimes.) So I’m not going to tour you through Stephens’s individual archetypes. I am, however, going to tell you about a grand irony they reveal about the art market’s default take on innovation, complete with a couple of counterexamples from the retail sphere.

The grand irony is this: While so many art sellers have spent part of the last 18 months (if not longer) trying to transition from a bespoke business powered by storytelling and in-person experiences, to a more mechanized business favoring seamless, repeatable, low-friction transactions (hi, online viewing rooms!), retailers have been trying to do precisely the opposite.

Interior view of an in-store production at Camp, a family-centric retailer using ticketed experiences to sell toys. Courtesy of Camp.

This is the ferment that has produced Camp, a toy store where toys take up only about 20 percent of the space in each brick-and-mortar location. The remaining 80 percent of the square footage is devoted to what the brand’s founder calls a “black-box theater of experience for kids and their families,” programmed quarterly by a team of Broadway veterans who write, design, and stage productions themed around the current slate of featured toys. (The company also sells tickets to the performances and sponsorships for each production.)

During the shutdown, Camp pivoted by creating virtual birthday parties with interactive video elements—far livelier than a PDF of activities that parents and kids have to turn into something memorable on their own.

It sells clothing, food, and gifts onsite as well, but its beating heart is creating engaging shows that motivate people to purchase items as mementos of something they could not have seen or done anywhere else. It’s about crafting a holistic presentation greater than the sum of its parts, which would normally just be neatly arrayed on shelves in hope of intriguing buyers who may or may not be encountering them for the first time.

Showmanship can lapse into gimmickry in a hurry in the art world, of course. But isn’t Camp’s ethos what curating an exhibition is all about?

Installation view of “Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images,” Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 19, 2006–March 4, 2007. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

We’ve seen how dealers can walk the line successfully in themed, set-designed art-fair booths in the past. Camp also reminded me that one of the most universally beloved shows during my Los Angeles years was LACMA’s “Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images,” which exhibition designer John Baldessari (!) enlivened with wall-to-wall carpets of Magritte-esque clouds, a ceiling plastered in overhead views of L.A.’s freeways, display walls built and painted to confound viewers’ visual perceptions, and museum guards dressed in black suits, ties, and bowler hats.

In contrast, I can’t be the only one reacting to the next four months of lightly modified art fairs, auction sales, and OVRs like a dog that’s just figured out midway through the car ride that it’s being taken back to the vet, right?

The point is, the art industry has largely been pirouetting away from showmanship and engagement at exactly the moment it should be doubling down. And that isn’t the only potential answer hinted at by forward-thinking retailers.

Stephens mentions the A/V superstore B&H Photo Video, whose sales staff consists entirely of expert photographers who are willing and able to guide customers through the labyrinth of buying and using often-expensive specialty equipment. The business thrives by offering A+ customer service—something the art world could use a lot more of, based on how many collectors have complained to me about unanswered inquiries sent to dealers’ online viewing rooms.

Instead, with just over four months to go before the start of our third year in the shadow of COVID, what the art market has shown is either a lack of recognition of the state of play, a lack of imagination regarding how to address it, or both. You don’t have to sell tickets to give viewers an experience that opens their bank accounts, and you can host transactions online without chaining yourself to the same rusty grid interface we’ve seen since the George W. Bush administration. (On the high end, some of the e-commerce strategies deployed by the likes of Alibaba make the mega-galleries’ online sales “innovations” look like cave paintings.)

If the pandemic truly ends before more of the art industry grasps how tentative its business evolutions look against the broader backdrop of retail, it certainly won’t be the greatest tragedy of this crisis. But it will be another missed opportunity in a historical period that risks being defined by them.

[Resurrecting Retail]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: the biggest problem with following the leader is that they might not have the right destination in mind.