The Art Detective

‘There’s Much Less Order Than Ever Before’: Auction Houses Are Entering the Post-Lockdown Era—But They’ll Never Be the Same

Market share is shifting from West to East and an evening sale doesn't mean what it used to.

Market share is shifting from West to East and an evening sale doesn't mean what it used to.

Katya Kazakina

The Art Detective is a weekly column by Katya Kazakina for Artnet News Pro that lifts the curtain on what’s really going on in the art market.

At 2 p.m. on Tuesday, 45 people gathered at an exclusive venue in London’s Mayfair district. Sitting around low tables, they sipped Ruinart Blanc de Blancs and munched on wild mushroom arancini. The setting could have been a private club or a cabaret. Instead, it was a Sotheby’s salesroom during the marquee evening sales of modern and contemporary art.

Occasionally, one of the invited guests would raise a hand to bid on a Pablo Picasso or Peter Doig. But for the most part, they were spectators—along with thousands of online viewers—of high-stakes bidding wars, live-streamed from New York and Hong Kong as well as London.

Canapés that were served to Sotheby’s guests at London evening auctions.

The event, which brought in more than $200 million, captures a market in flux one year into the global pandemic. With more vaccinations and fewer restrictions, Sotheby’s, Christie’s and their smaller rival Phillips are exploring a truly hybrid auction model. Coordinated schedules, longstanding categories, in-person previews, and a live audience—all have been tossed into the air as each house pursues its own strategy and tries to innovate while coping with unprecedented disruption.

“For so many years, clients would call and say, ‘The catalogs are late. Where are my catalogs?’” said David Norman, chairman of the Americas at Phillips. “Now there are barely catalogs any longer. Categories are blurred, sale dates aren’t aggregated the same week. There aren’t big dinners or cocktail parties. Selling exhibitions have been reduced. And yet it seems like everyone adapted overnight. We didn’t lose the audience.”

It’s hard to predict what the auction world will look like a year from now. Which business model will prevail? Will Paris or Hong Kong supplant London as the second global art-world capital? What other cities will become important power centers? And how will the auction houses build critical mass and engagement around numerous sales that seem to look more and more alike?

Preparing for a hybrid live-streamed in person sale at Sotheby’s.

The past year forced the houses to move online and “reinvent the calendar spontaneously,” said Brooke Lampley, Sotheby’s chairman and worldwide head of sales for global fine art. “As a result of that, we landed in a place where there’s much less order than there ever was before.”

Some terminology may need to be updated. This week’s London “evening” sales began early afternoon local time to accommodate Asia, a growing market power where it was in fact evening; New York, the art market’s epicenter, was in the middle of the morning rush.

“There’s a joke: It’s always 5 o’clock somewhere,” said Christie’s chairman Alex Rotter.

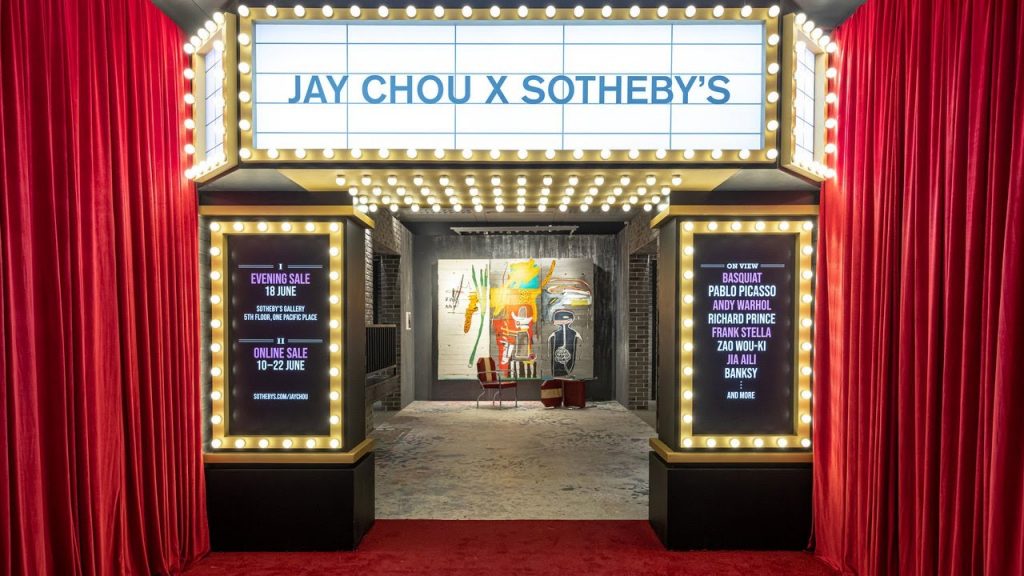

Timing is important in the era of live-streamed auctions. Evening sales in New York are convenient for Asia, but have kept London and Europe up into wee hours. Last week, Phillips’s day sale in New York went from 10 a.m. to 8 p.m., which meant an all-nighter for its Hong Kong staff—and any Asian collector who wanted to bid on, say, Lot 320, a painting by young star Flora Yukhnovich, which soared to more than 12 times its estimate.

Flora Yukhnovich, Pretty Little Thing (2019). Photo: Phillips.

Timing also telegraphs the shifting importance of various regions. Most houses are trying to accommodate Asia, whose appetite for art investing seems to be insatiable at the moment. At Sotheby’s, 45 percent of bidders on lots with a low estimate of at least $5 million were Asian in 2020–2021, compared with 32 percent two years earlier, the company said.

But the region is not optimized, according to Lampley. Supplying Asia with art “is certainly one of my foremost priorities. New York is pretty saturated with supply. Asia is under supplied and over-performing from a buyer perspective.”

A case in point: Out of about 190 abstract paintings by Gerhard Richter at auction from 2018 through 2020, just 11 came up in Hong Kong, according to the Artnet Price Database. Last year, Sotheby’s bucked the trend and sold Ronald Perelman’s Richter for $28 million, shattering its $18 million high estimate. “Dislocated and put into a different market, it was able to fly,” Lampley said.

A Gerhard Richter painting consigned by Ron Perelman at Sotheby’s Hong Kong. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

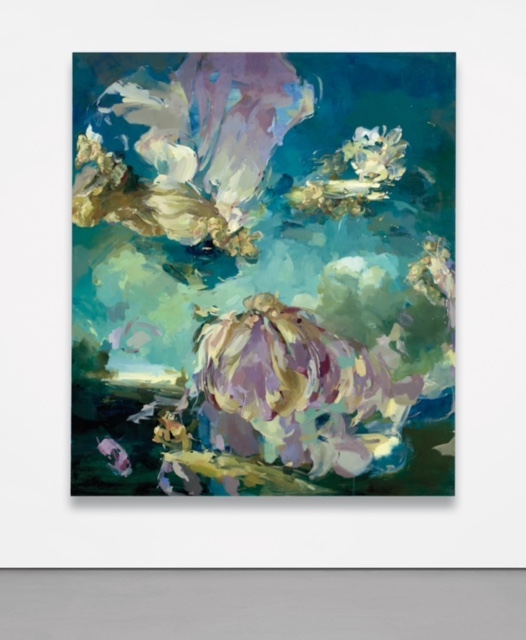

Asian demand has been strong enough during the pandemic that Hong Kong auctions at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips fell just 3 percent, to $1.05 billion, in 2020, compared with a 43 percent drop in New York and 38 percent decline in London. This year is poised to be a record for the hub, with almost $900 million worth of art sold to date, according to the Artnet Price Database.

“Five years ago, if I told someone that I wanted to sell their work in Hong Kong instead of New York, that would have been a significant conversation,” Lampley said. “Today they don’t even flinch.”

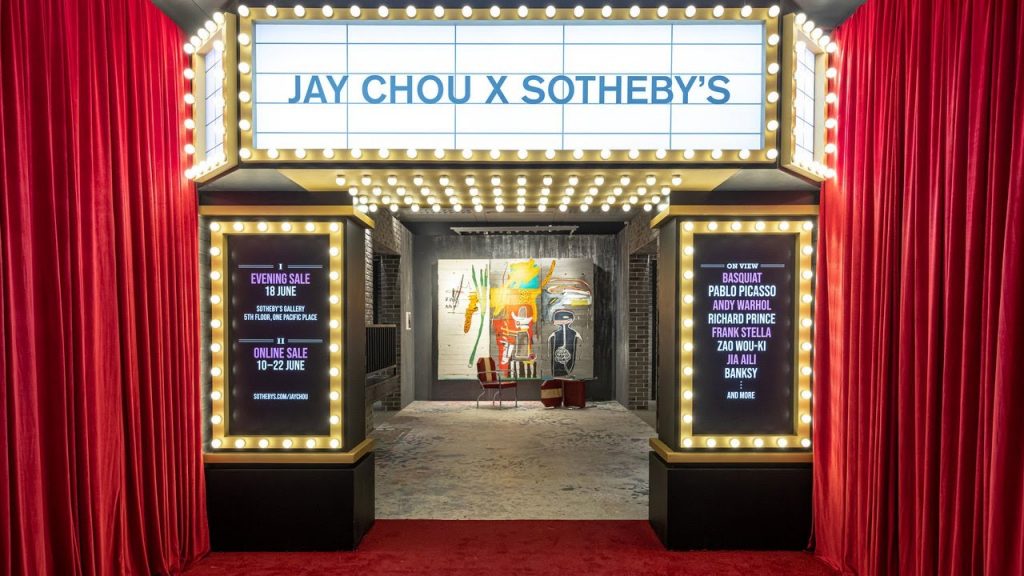

Bill Acquavella and Jose Mugrabi, two powerful New York dealers, recently consigned a major 1985 Basquiat triptych they co-owned to Sotheby’s sale in Hong Kong curated by Taiwanese pop star Jay Chou. It fetched $37 million earlier this month.

© Artnet Price Database and Artnet Analytics 2021.

“There was Asian interest in the picture. We got a guarantee and we went for it,” Acquavella told us. “It’s a new market and it looks very strong in the long run.”

Nevertheless, he added, “It’s not like New York has lost its power.” Certain marquee collections, including those of Harry and Linda Macklowe, would probably still be sold in Big Apple. Not to mention concerns over censorship in Hong Kong as Beijing tightens its control over business, politics, and culture.

“We are all clear that Asia is next big thing,” said Christie’s Rotter. “For the near future, I don’t see the position of New York changing. The big question is Europe.”

16th October 1958: Television cameras in a crowded sale room at Sotheby’s where seven impressionst paintings were sold for an unprecedented amount. (Photo by Central Press/Getty Images)

Brexit and COVID restrictions have had a chilling effect on London’s market. Meanwhile, Paris has emerged as an attractive alternative, with its growing gallery scene, active collectors, and new museums such as Francois Pinault’s Bourse de Commerce.

“Paris is becoming more and more important to us and the global market,” said Robert Manley, deputy chairman at Phillips, which doesn’t currently conduct auctions in the French capital. “Gradually, you’ll see more business shifting there.”

In a globalized world, one might assume that the location where an artwork is sold has never mattered less. But the shifting energy has significant implications for the trade: it informs where auction houses invest, where they staff up, and where they proactively cultivate collectors—all of which can have a trickle-down effect on the local art ecosystem.

Sotheby’s, for its part, is planning to launch auctions in Cologne, Germany, and has been experimenting with pop-up private spaces where the rich have fled during the pandemic, such as the Hamptons, Palm Beach, and Monaco.

“We are definitely in a modus adaptation,” said Lampley, “or evolution.”