The Art Detective

What Went Wrong With Christie’s Fineberg Sale, the Auction That Nearly Drove the Art Market to Despair? Plenty.

At first, people were stunned to see art by major names selling for a pittance. Then they got excited.

At first, people were stunned to see art by major names selling for a pittance. Then they got excited.

Katya Kazakina

Let’s talk about the sale that almost tanked the art market.

I’ve covered many auctions during my career as a reporter. Most are a blur. A few are memorable because they took the market to unexpected highs or brought it down to surprising lows.

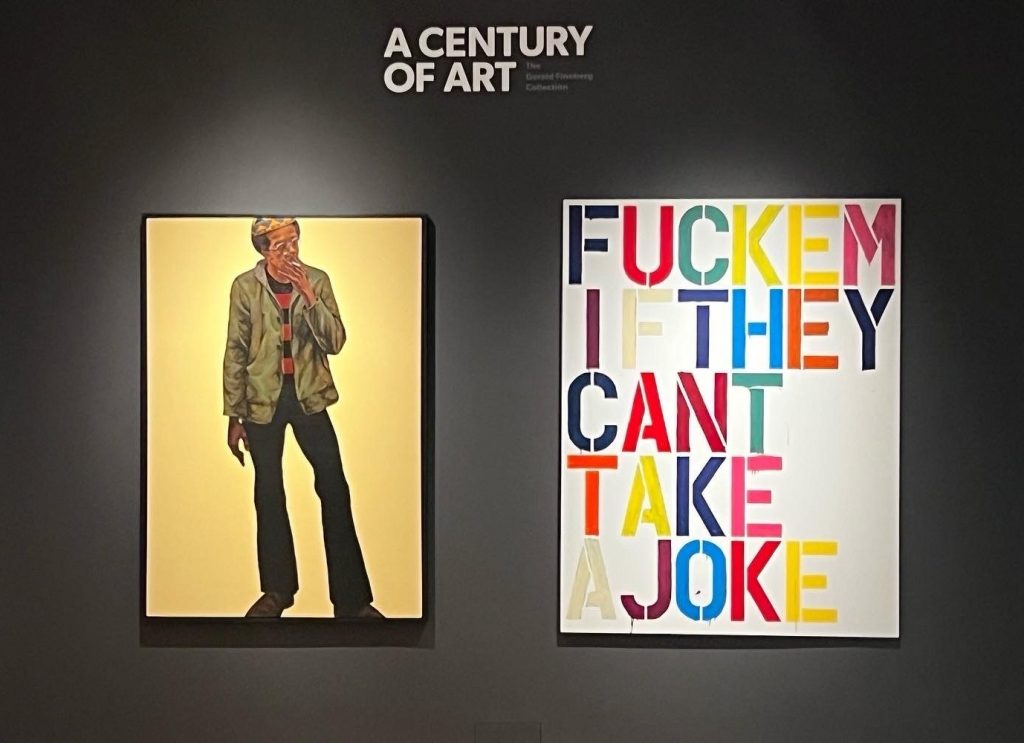

The evening sale of the Gerald Fineberg Collection was a textbook example of a reset happening in real time in front of our very eyes. Bidders seemed stunned into inaction as lot after lot sold on a bid or two at huge discounts compared to their presale estimates. Richter, Krasner, de Kooning, Wool, Fontana, Lichtenstein—all at fire-sale prices. Grotjahn, Rosenquist, Bourgeois, Kippenberger—unsold.

By the following day, the shock gave way to excitement: “Bargains!” People began shopping for lower-value artworks, filling up on deals like Walmart customers on Black Friday.

Christie’s Global President, Jussi Pylkkänen, sells Barkley L. Hendricks’s Stanley (1971) for a record-breaking $6.1 million. Photo courtesy Christie’s.

In the end, most of the 214 lots found buyers. Christie’s totaled $159.8 million (excluding its buyer’s premium), well beneath the presale estimates of $198 million to $286 million (although records were set for artists including Barkley L. Hendricks and Alma Thomas). There are still many, many lots left to sell. Some will be included in upcoming Hong Kong auctions at the end of May, the New York design sale in June, and other, yet to-be-announced events, according to Christie’s.

There are lingering questions about how the sale was handled—and what its long-term impact might be. John Silberman, an attorney who represented the estate, didn’t respond to calls or emails seeking comment. Christie’s executives said they advised the Fineberg estate to lower the reserves in order to adjust to the changing market conditions.

“It’s not a great outcome for the owners—or the market,” an auction executive at a rival company said.

One thing we know: the heirs had very bullish expectations for the auction and decided not to accept a guarantee (which I hear was north of $200 million). Instead, they pushed for—and got—an aggressive enhanced-hammer deal, thereby sharing a big chunk of Christie’s buyer’s premium (which so far generated about $37.4 million). In hindsight, they left money on the table.

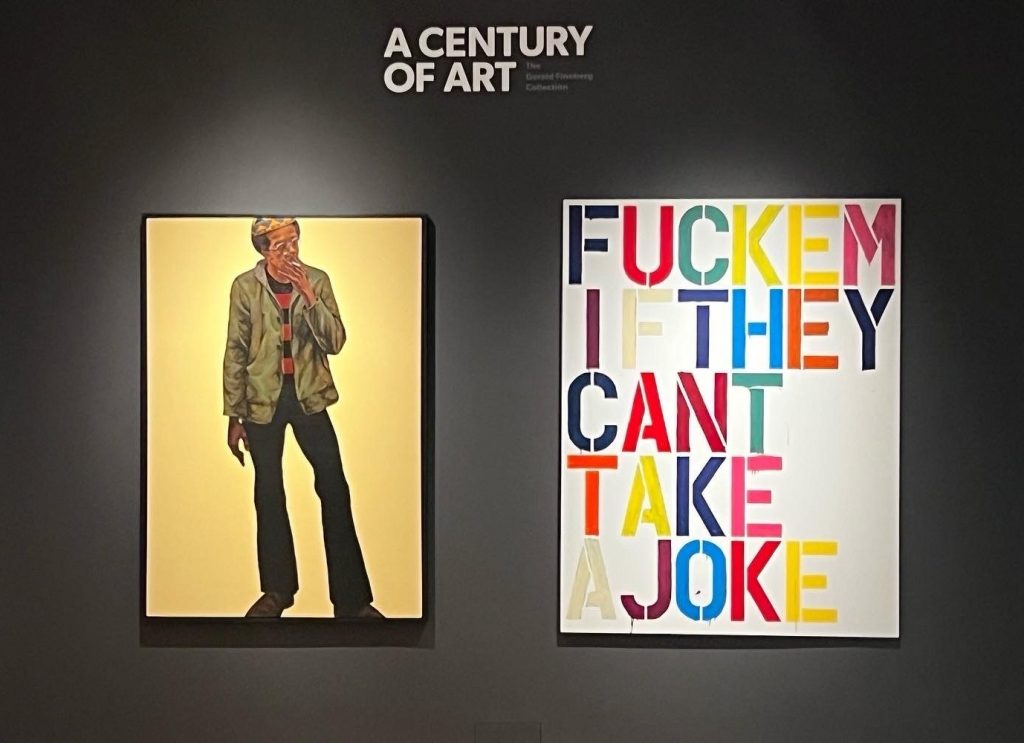

Christopher Wool, Untitled (2000). © Christie’s Images Ltd 2023.

To be fair, so did the estate of Mo Ostin at Sotheby’s, market participants pointed out. Ostin’s heirs also would have been better served taking a guarantee (although that estate did take four irrevocable bids in the 11th hour; the Fineberg heirs had refused all such offers).

Amid the recalibrating market reality, one moral of the story is clear. “If someone is willing to give you a guarantee for a picture, sometimes it’s better to take it than to go in naked,” as one major art buyer put it.

And another note to sellers: Don’t be greedy! Let the auction house make some money too.

Why? The construction of the Fineberg sale seems to have had a demotivating effect at Christie’s, where the people calling the shots may not have been financially incentivized to work their hearts out for the collection, several people said.

“There’s a point where the deals don’t make sense for the amount of time and effort,” said the auction executive. “There are hundreds of items that had to be packed, shipped, unpacked, installed, deinstalled, insured—that all costs money. Working for 2 percent, theoretically, is not that exciting.”

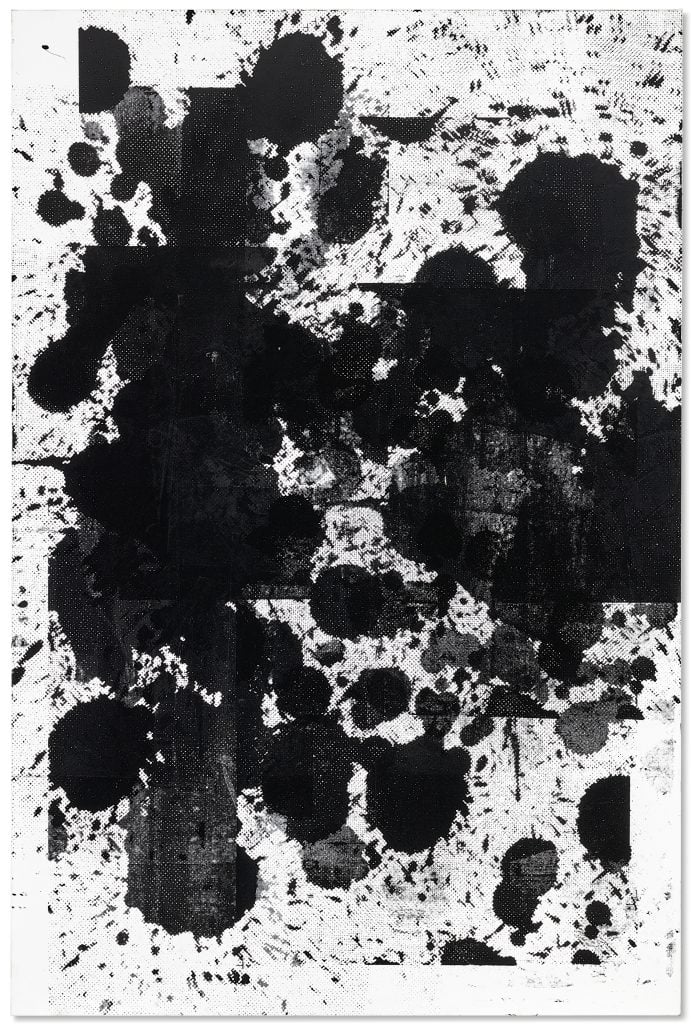

Gerhard Richter, Badende (1967). Courtesy of Christie’s.

The Fineberg highlights were installed salon-style in a hallway during the first auction week, while more prime galleries exhibited single-owner collections of media billionaire S.I. Newhouse and Chicago’s Alan and Dorothy Press. By the time the group was rehung more centrally, many of the European buyers touring through the previews had already gone back home.

Within days of the sale, the estimates—which had been set in January—suddenly seemed out of step with the sobering reality of debt-ceiling negotiations and a teetering banking sector. (It’s an old game: competing auction houses feel compelled to put high estimates in order to win the material.) The estate agreed to slash the reserves but still refused to accept third-party guarantees. Time was ticking.

Ultimately, the whole unfunny comedy of errors may have boiled down to the quality and quantity of material.

Christie’s built its narrative around vision and passion of the Boston-based real estate billionaire, who died in December, emphasizing his “curator” thinking and the collection’s span from Man Ray’s 1923 portrait of his lover and muse Kiki de Montparnasse to ultra-contemporary works created a century later.

“They tried to make it seem like it’s the Mona Lisa coming for sale,” the major art buyer said of Christie’s efforts. “The market is not stupid.”

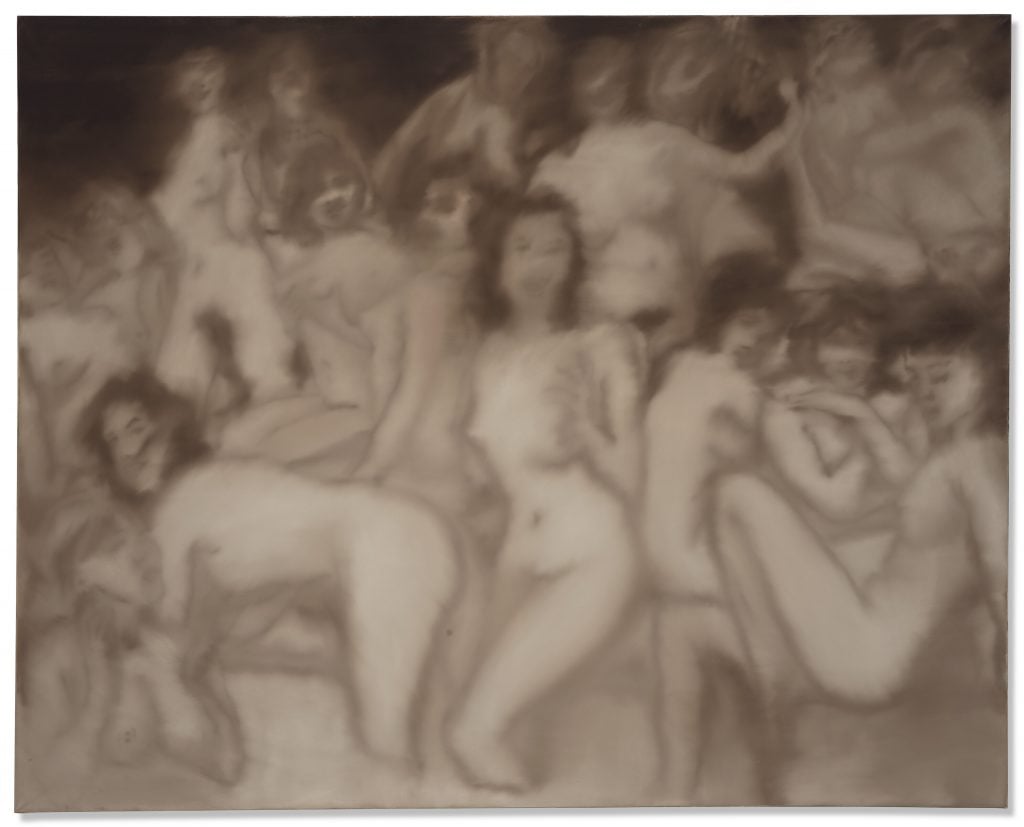

Lee Krasner, Twelve Hour Crossing, March Twenty-first (c. 1971–81). Courtesy of Christie’s.

But those who knew the Fineberg collection pointed out that, in fact, it reflected the eye of a longtime adviser, the behind-the-scenes collector-wheeler-dealer Michael Black, who wasn’t mentioned in the catalog.

“I am amazed at the narrative that emerged,” said a New York art adviser. “Literally a lot of these works he bought in the past three-four years from Michael Black.”

Other people in the know saw Fineberg as more of a haggler than a visionary.

“Jerry was a hondler,” said a dealer who sold many works to Fineberg. “You offered him a great thing for a price and an average thing for a discount, and he’d always take the one with a discount.”

Black, it so happens, was instrumental in shaping the collection during the past two decades.

“We had a lot of fun,” Black told me this week. “Buying art for him, it kept him alive. It gave him something to do.”

A few years ago, Black got Fineberg a book, Ninth Street Women, about Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Lee Krasner, Helen Frankenthaler, and Joan Mitchell. “Those women are good,” Black said. Soon their paintings entered Fineberg’s collection.

Some of them did incredibly well at Christie’s day sale. Hartigan’s On Orchard Street (1957), purchased in 2019, fetched $1.2 million, 12 times the low estimate of $100,000. Krasner’s 1975 untitled oil-on-paper, also acquired in 2019, sold for $1.2 million, more than twice the low estimate of $500,000.

Lynne Drexler, Summer Blossom (1962). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

One of Fineberg’s last purchases was Lynne Drexler’s Summer Blossom, which fetched $1.4 million at Christie’s day sale, compared with the low estimate of $150,000. It was the second highest price of the day sale. “I bought it for him when he was dying,” Black said. “I wanted something pretty for him to look at when he goes to the bathroom.”

So, the Fineberg collection didn’t tank the market, after all. And, for some people, the key takeaway was art’s resilience as an asset class.

“It was an incredible opportunity,” said the major art buyer. “This is what smart people do. They buy when things are down and they sell when things are up.”