The summer of 1995 was poised to be a dream come true for one group of recent graduates from the New York Academy of Art. They were the select few who’d been chosen from their class to go on an all-expenses-paid trip to New Mexico to study under the prestigious painter Eric Fischl, to attend the debut of the newly launched Site Santa Fe biennial, and to meet with a wealthy benefactor who wanted to buy emerging artists’ work.

The patron was said to be building a vast mansion on his ranch in New Mexico and, at the end of the trip, would commission one of the students to paint a mural at the completed house.

“There was a feeling that someone was going to come out of this an art star,” Ursula Ruedenberg, one of the alumnae on the trip, told Artnet News.

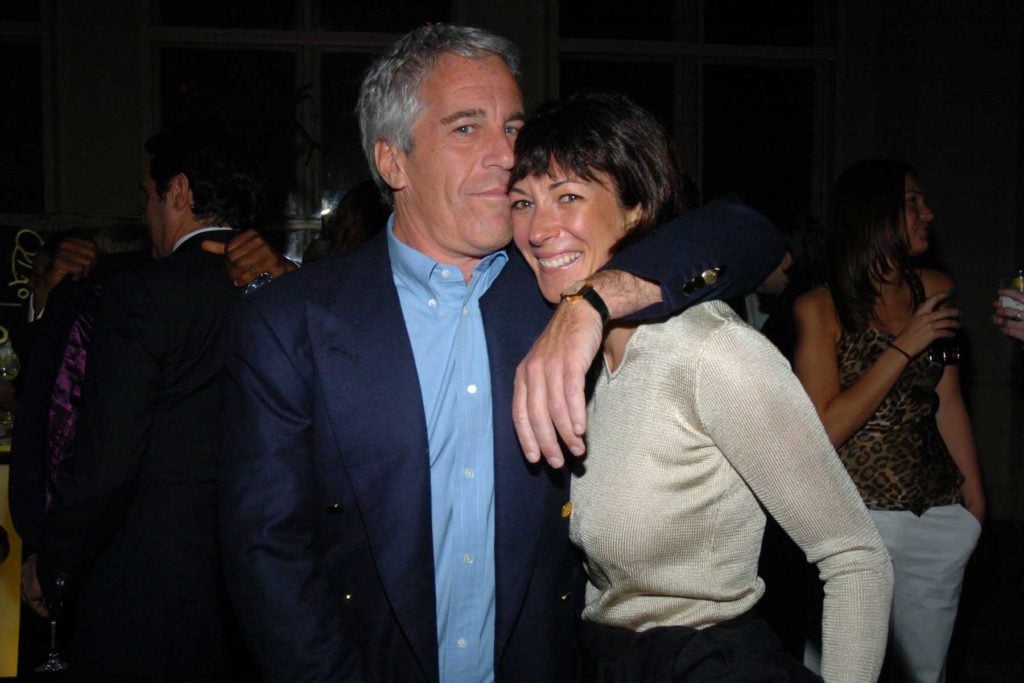

There was just one problem: The patron was Jeffrey Epstein, the convicted sex offender and pedophile who died in a New York City jail in August. The encounter with Epstein on his ranch, detailed to Artnet News by three of the alumnae (one of whom spoke on the condition of anonymity), sheds fresh light on how Epstein exploited the ambitions of aspiring artists by promising sales and connections, all while testing their boundaries and, ultimately, allegedly assaulting one of them, Maria Farmer, Epstein’s first accuser.

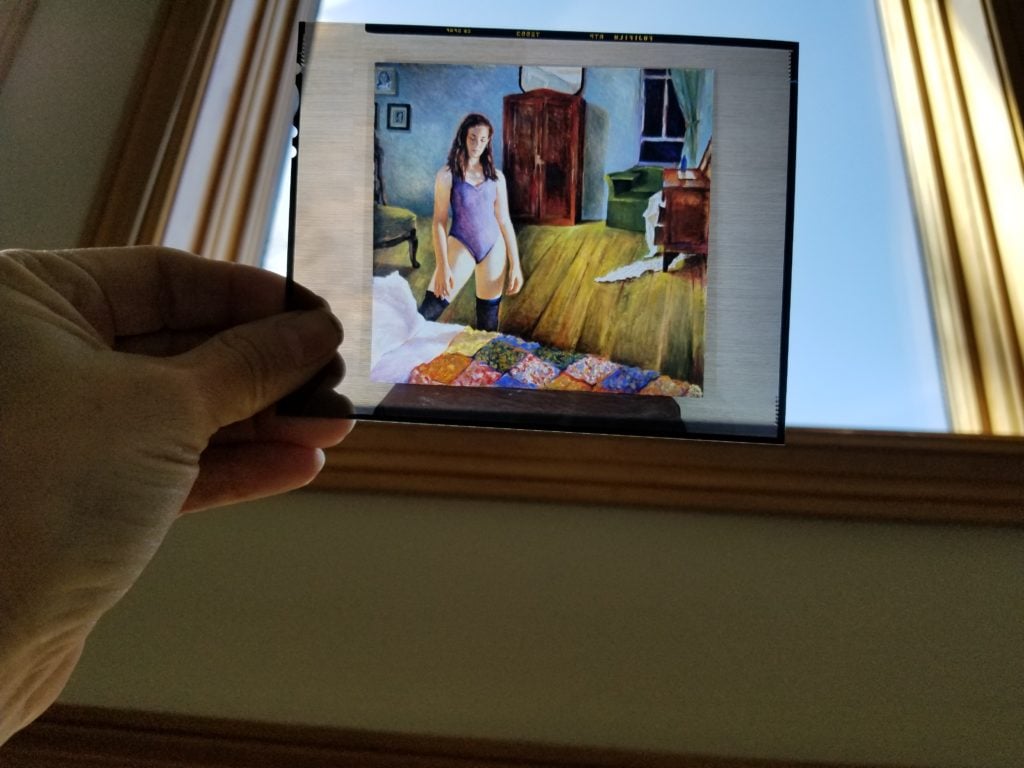

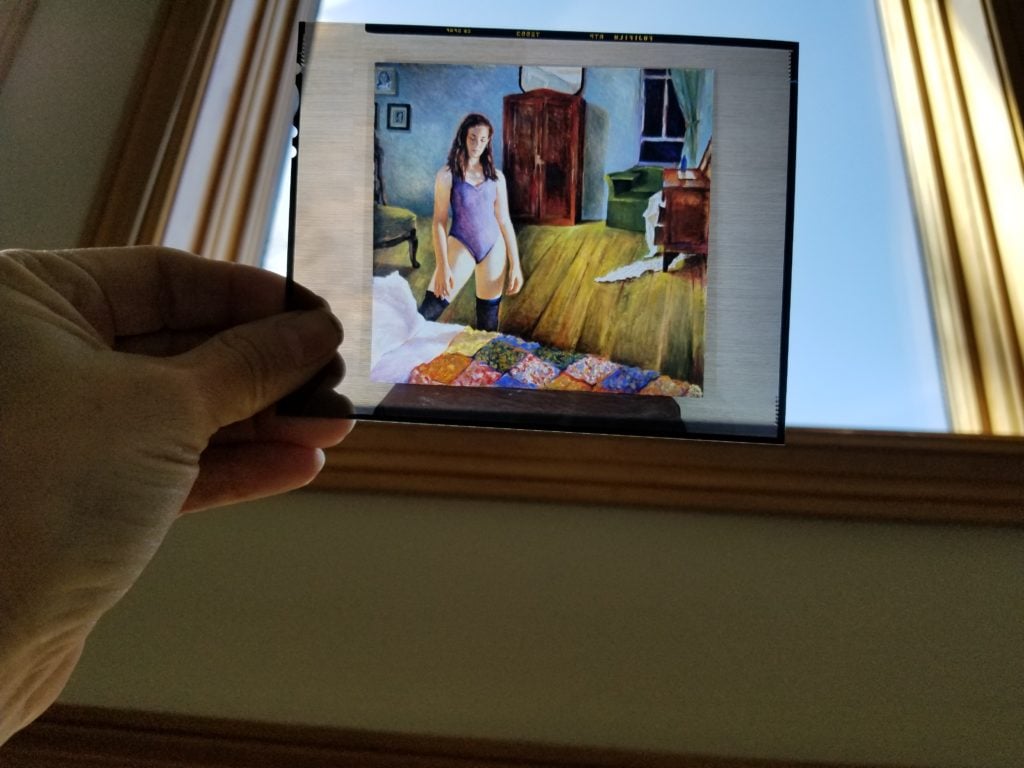

Maria Farmer holds an image of a painting she made during the alumnae trip to New Mexico and gave to Epstein.

Conflicting Memories

Epstein had purchased the 10,000-acre Zorro Ranch on a mesa between Santa Fe and Albuquerque two years before the alumnae trip. At the time the students arrived, he was in the process of building a Wild West-style village on the property, complete with a saloon and general store. This was where numerous women would later say they were trafficked and raped, and where Epstein plotted to mass-impregnate women and “seed the human race with his DNA,” according to the New York Times. But for now, his future mansion had yet to be built and he was living in a temporary trailer on the land with his accused co-conspirator Ghislaine Maxwell.

The alumnae say they were brought to the ranch by Eileen Guggenheim, then dean of students at the New York Academy of Art and now chair of its board, who was friendly with Epstein because he had been an academy trustee for the past seven years. When Artnet News first reported Maria Farmer’s account of how Guggenheim encouraged her relationship with Epstein, in part by bringing her to the ranch, Guggenheim responded that the story was “a serious mischaracterization. I have never been at Mr. Epstein’s home in Santa Fe.”

However, earlier this month, a second alumna contacted Artnet News to corroborate Farmer’s story—saying that she, too, had been at the ranch that day and confirming that the meeting with Epstein, Guggenheim, and the students did indeed happen. “Guggenheim’s misrepresentation appears to aim at dismissing Farmer’s concerns—but kind of raises new ones,” she wrote.

A third former student confirmed that the trip with New York Academy of Art students to Epstein’s home occurred, and that Guggenheim was present, but remembered few further details.

“There may be some confusion about my visit 25 years ago to Mr. Epstein’s property,” Guggenheim told Artnet News when asked about the additional accounts. “What I remember is visiting an old-fashioned Western town that Mr. Epstein had apparently purchased and was under construction. To the best of my recollection, I did not visit any home there or have a meal there.”

Jeffrey Epstein’s Zorro Ranch in New Mexico, as seen on Google Earth.

A Day on the Ranch

Both Farmer and Ruedenberg say that they felt unsettled from the moment they arrived on the property.

“It was a huge scary ranch on this big, ugly, dry desert,” Farmer recalled in a recent conversation with Artnet News. When Epstein gave them a tour of the grounds, he kept pointing out how many deadly rattlesnakes lived on the land. After they returned to the house, Maxwell instructed the students to put their coats in the closet. When they opened the door, they found a skeleton hanging inside.

“She was disappointed that we weren’t frightened by that,” Ruedenberg said. “She thought that we would be afraid of a skeleton—but as art students, all we do is look at skeletons.” For the rest of the day, “they proceeded to pull pranks on us all the time, to make us feel unstable,” Ruedenberg recalled.

The odd stunts continued at supper, when Epstein and Maxwell instructed their guests to close their eyes as they passed around a bag of unknown objects, and to reach inside and guess what they were. “One was what felt like pockets of jelly; it turned out to be falsies, like you put in your bra,” Ruedenberg said. “Then they demanded that we put them on.”

Ruedenberg refused and immediately felt shunned for not playing along. “I knew the commission was out the window at that very moment,” she said. “I could see it was a question of ‘how far will they go? Does this person have boundaries?'”

“It was the weirdest dinner party I’ve ever been to all my life,” she added. “I’ve been around a lot of rich people in New York and many are misbehaved, but this was another level.”

Farmer, who later went on to work for Epstein in New York, says that this was a party trick he often liked to play with sexual objects such as condoms. Maxwell’s role was to “normalize” it, Farmer said. “She had a light-hearted delivery so you never felt like—dun dun dun—you’re going to be kidnapped and raped. You just thought they were quirky and they love art.”

Ruedenberg says that Guggenheim and Maxwell treated her like a “square” after she declined to play along. “That dinner party should not have happened, it was inappropriate. I feel like when you’re in a position of responsibility to students and somebody acts the way they did, that’s cause to step back and assess whether this is a professional situation or not, and that definitely did not happen.”

Guggenheim says that she was not aware of any students taking issue with the encounter. “Had any student expressed to me their personal discomfort over actions by Mr. Epstein,” she told Artnet News in an email, “I would have immediately addressed the situation and offered my support. At that time, however, neither I nor anyone at the New York Academy of Art had any knowledge of Mr. Epstein’s predatory behavior.” (Epstein was first jailed for sex crimes in 2008.)

A painting Maria Farmer made during the alumnae trip to New Mexico and gave to Epstein.

Dangling a ‘Plastic Carrot’

Epstein’s promise to buy one of the students’ work from their summer class in Santa Fe, and then to commission them to create a mural, was “part of the conversation throughout the day,” Ruedenberg recalled.

“There was always that plastic carrot,” Farmer said. But both women say that Epstein never bought their work after the trip. Farmer says that she gave Epstein the two paintings she made there at Guggenheim’s urging, but was never paid for them. (Guggenheim previously told Artnet News that she has “never forced an art sale by an Academy student.”)

After Farmer returned to New York, Epstein hired her as his art adviser and she later traveled to Ohio to work on an art project at the estate of his friend Leslie Wexner, the billionaire businessman. That’s where Farmer claims that Epstein and Maxwell sexually assaulted her. Around the same time, the pair allegedly invited Farmer’s 16-year-old sister, Annie, to the New Mexico ranch under the guise of a student trip. When she arrived, Annie said nobody was there except Epstein and Maxwell, who allegedly assaulted her, too.

Farmer says that Epstein and Maxwell threatened to ruin her career if she spoke out about what happened. Instead, she moved away from New York and, for a long time, stopped painting.

Ruedenberg, too, says that although she didn’t experience anything like what Farmer went through, the experience with Epstein soured her on the art world. “I was so fed up with that whole scene, and [Epstein] was part of it,” she said. “I left New York. I just thought, I don’t want to paint for these people, and I stepped out of that whole world.”