Law & Politics

The Brooklyn Gallerist Who Artist Deborah Roberts Is Suing for Copyright Infringement Has Fired Back, Calling It a Case of ‘Punching Down’

Richard Beavers has filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

Richard Beavers has filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit.

Eileen Kinsella

A Brooklyn gallerist and an artist he represents are pushing back against a copyright infringement claim brought by Deborah Roberts, a sought-after artist.

Texas-based Roberts shot to fame in recent years with her collage-based portraits of Black children in various formats and styles. Her work is now held by museums across the U.S., and she is represented by prominent galleries including Susanne Vielmetter in Los Angeles and Stephen Friedman in London. The Artnet Price Database lists 10 auction results for Roberts, the highest price of which is $275,000 for a mixed media work, I Do Solemnly Swear (Nessun Dorma series) (2018), sold in November 2021.

In September 2022, Roberts sued Brooklyn gallerist Richard Beavers and an artist from Alabama named Lynthia Edwards who she accused of “willful copyright infringement” along with unfair competition and market dilution.

Now, Beavers and Edwards have fired back, with a request that the court, which is the U.S. District Court, Eastern District of New York, dismiss the lawsuit.

“This case is about an artist at the height of her career punching down on an emerging artist in order to stifle market competition and eliminate a competitive threat,” according to the dismissal request. “But the fact that both artists use the collage style or feature children in their artworks does not support a copyright infringement claim. The use of photo-based collage has deep roots in the work of Black American artists, and there is a long line of artists before Roberts who have worked in this same general style.”

The court papers assert that the only similarity between the artists’ work is that both fit into “a long established historical tradition that Roberts neither invented nor owns.” And that while Roberts is deserving of all the accolades she has been receiving, “she did not invent and does not own the concept of depicting Black figures through collage.”

Roberts’s attorney did not respond to a request for comment.

Maaren Shah, a partner at Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, told Artnet News via email: “We’ve very bullish on our legal defense. There is no precedent for copyright protections on an artistic style, let alone one like collage, which has such a long and rich history. What we have here is a clear case of an established artist with powerful galleries punching down to hurt the prospects and career of a longstanding member of the art community. We’re confident those facts come through clearly in our motion to dismiss.”

Image courtesy Pacer

The dispute is clearly a heated one. According to the latest filing, Roberts tried to pressure Beavers to stop representing Edwards. She left Beavers a voicemail saying: “I see that you’re representing that girl in… Alabama who’s ripping off my work. And I did get an attorney on her… she has no money. That’s the only reason I haven’t sued her. But I’m telling you right now, if she continues to show my work and do my work, I’m gonna make it public. Public. The New York Times. I don’t care what I have to do, I’m gonna squash this.”

The filing claims that when Roberts’s threats to Beavers did not work, she “used her influence in the art world to encourage patrons and collectors to boycott RB Gallery in hopes of pressuring the gallery to drop Edwards.”

The 32-page filing asserts two related points. First that Roberts’s complaint fails to state a claim for copyright infringement since Second Circuit precedent is clear that “stylistic and thematic elements are not protectable as a matter of law.” Second is that the complaint fails to state a claim for “trade dress,” a reference to the characteristics of the visual appearance of a product or its packaging that signify the source of the product.

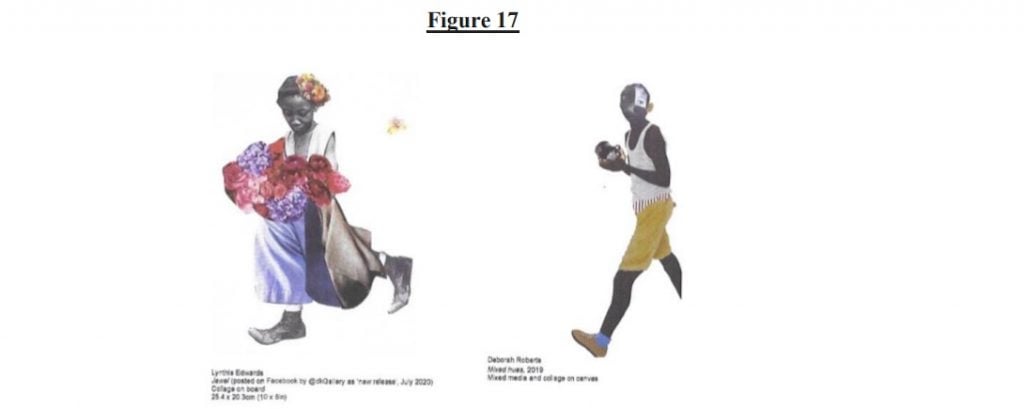

The latest filing addresses a side-by-side visual included in Roberts’s complaint that compared Edwards’s Jewel (2020) to Roberts’s Mixed Hues (2019). “Besides the obvious difference that Jewel features a girl and Mixed Hues features a boy, Jewel’s subject holds a large, overlapping assemblage of brightly colored flowers—which is entirely absent from Mixed Hues—and uses entirely different colors to the palette in Mixed Hues.”

It continues noting that the girl in Jewel is wearing a voluminous, mixed-color, and collage-style skirt and exaggerated, oversized boots, whereas the boy in Mixed Hues is wearing proportional and flat shoes and shorts. “The only similarities between the works are that they depict Black children walking against a colorless background—all unprotectable elements that are not, and cannot be, unique to Roberts’s works,” according to the document.

Image via Pacer.

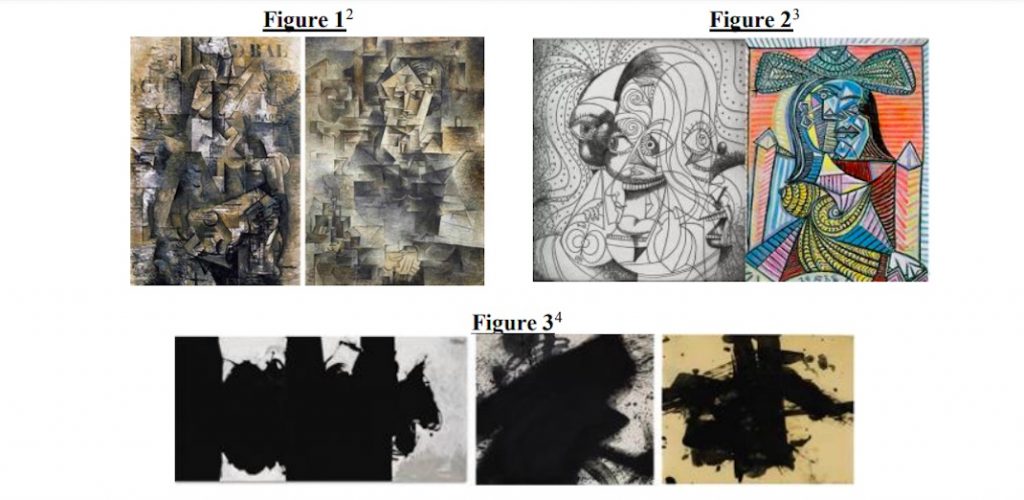

The complaint goes on to make other side-by-side visual comparison of stylistic similarities throughout art history, such as between Picasso and Georges Braque, and Frank Kline and Robert Motherwell, while noting ”Pablo Picasso did not own the exclusive right to depict people in the cubist style… and Franz Klein [sic] did not own the exclusive right to paint abstract black marks inspired by ancient calligraphy.”

The complaint further notes that the practice of collage involves using source material created by someone else and so is already appropriated from an earlier source. “Roberts cannot sue Edwards for infringement for using source material created by a different artist that Roberts herself also used,” according to the document.

More Trending Stories: