Art & Tech

New Technology Shows Museum Visitors How Art Activates Their Brains

The technology reveals how our brains react differently to an Impressionist masterpiece of an abstract painting.

The technology reveals how our brains react differently to an Impressionist masterpiece of an abstract painting.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

Our appreciation of good art has always had an intangible and essentially unknowable quality. But now, everyday museumgoers may be able to get new insights into how their brains respond to what they see. The U.K.’s Art Fund has launched a project that visualizes brainwave activity in real-time to measure our reactions to different works of art. The initiative was piloted at the Courtauld Gallery in London earlier this month and will tour to select U.K. museums in 2024.

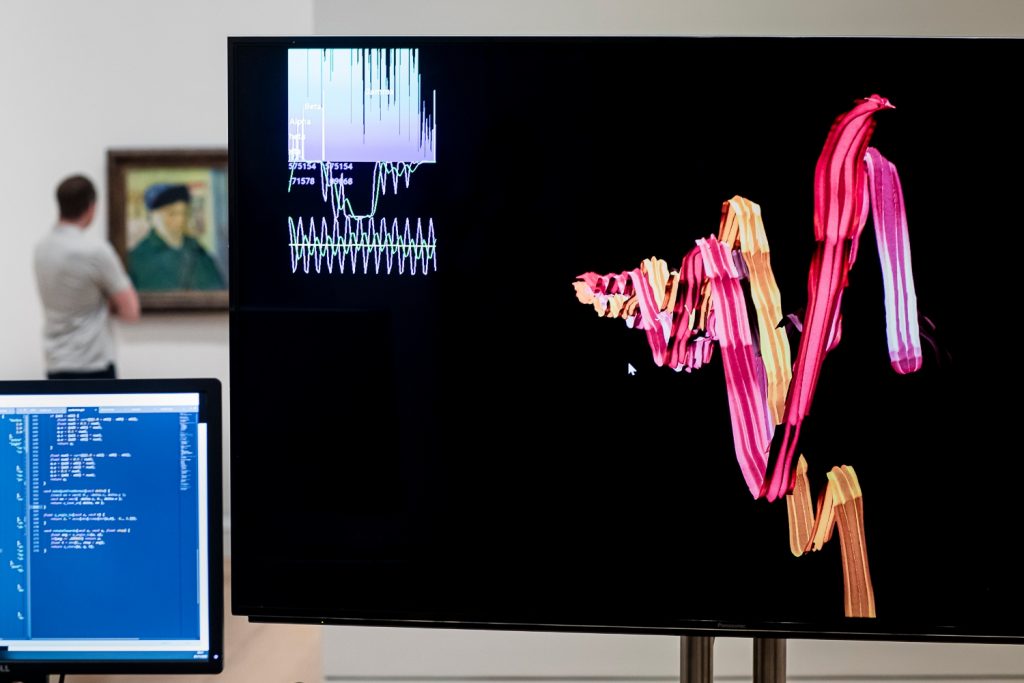

Last week I tried out the technology, which uses a slim, wireless headset that presses sensors against the forehead and tucks behind the ears, a bit like wearing glasses. The brainwave data is transmitted in real time to a large screen at the center of the room that is operated by an expert, who is busy watching your mind’s every move. When I slipped on the headset, I was pleased to see immediate evidence of brain activity, demonstrated by the looping and undulating ribbons that began to swirl across the screen. I set off around the room, perhaps overly conscious of the need to think normal thoughts and react to the art as I would under normal circumstances.

I later learnt that while I was taking in some calming still-lifes by Patrick Heron and Matthew Smith, my ribbons began to glow, exhibiting lighter gold threads that indicate I had stumbled across something that felt familiar. Then I approached the considerably murkier Shell Building Site (1962) by Leon Kossoff, a large canvas densely covered in thick, impastoed paint that has a strongly abstracting effect. My ribbons began spinning into a corkscrew shape that apparently signifies deep thought or problem-solving. Unsurprisingly, I showed noticeably fewer of either brainwave pattern while I was merely crossing the room.

Brainwaves on screen with Van Gogh in background. Photo: Hydar Dewachi, courtesy of Art Fund.

Of course, the shapes I was seeing on the screen are a simplified, 3D visualization intended to make the raw data intelligible to a laywoman like me without much expertise in neuroscience. After the electroencephalogram (EEG) headsets collect the data, the system isolates a specific frequency of brainwave activity known as the beta range. “There are other frequencies that are more to do with unconscious thinking, but beta waves are about your conscious thought,” said Will MacNeil, creative director of The Mill design agency, which produced the visualization. His team decided that recognition and intense reflection were among the most relevant thought patterns for art appreciation. “We’re trying to create an impression of what’s going on in your brain that is also nice to look at,” he added.

My results will have been impacted by the fact that I was in a gallery filled with 20th-century British art, including lots of abstract paintings. The brainwaves recorded on participants who walked around the neighboring gallery containing famous masterpieces by artists like Van Gogh, Manet, and Cézanne tended to show more glowing threads of recognition than corkscrews of confused contemplation. “Whether you mean to or not, when you walk up to a piece of abstract art, you tend to try to understand it,” MacNeil said. “Whereas if you’ve seen a painting before, you’re going to have a very different response and look at it probably in a less objective way.”

Art Fund commissioned the project in response to the statistic that around 40% of Brits visit a museum or gallery less than once a year, and 1 in 6 said art had no effect on them. The charity hopes that providing the brainwave data will be a fun, interactive way to show how art impacts people’s minds and emotions and that this will help motivate new audiences.

A real neuroscientist, Dr Ahmad Beyh from Rutgers University, was also on hand to clarify that the lightweight, wireless EEG headsets in use around the galleries are a far cry from the methods used in lab-based scientific analysis. Nonetheless, their ability to capture data in real-time makes them “a brilliant way to bridge the scientific world and the art world, and see how art is engaging the brain.”

One of Beyh’s main research interests is how our brains apprehend beauty. “A heightened experience of beauty, whether in art, music, or other people, correlates with heightened activity in the area just behind the middle of the forehead, called the medial orbitofrontal cortex,” he said. “The same region is implicated in experiences of pleasure, the experience of reward and seeking reward, and also in introspective thought or daydreaming.”

More Trending Stories:

Revealed: The Major Mystery Consignors of New York’s Multi-Billion-Dollar Fall Auction Season

Christie’s Pulled Two Works by a Prominent Middle Eastern Artist From Sale After a Complaint