Curiosities

Why Does ArtReview’s ‘Power 100’ Skip Over the Actually Powerful? + Other Questions I Have on the Week’s Art News

Plus, what do art audiences really want?

Plus, what do art audiences really want?

Ben Davis

Curiosities is a column where I comment on the art news of the week, sometimes about stories that were too small or strange to make the cut, sometimes just giving my thoughts on the highs and lows.

Below, some questions posed by the events of the last week…

That’s not a rhetorical question. Really, what is the ArtReview Power 100? I can’t figure it out.

Last week, the 2021 ranking of the 100 most powerful people in art was released, and topping the whole thing was “ERC-721,” the first “non-human entity” ever to make the Power 100 ranking (sorry “gravity” and “three-dimensional space,” your time will come).

If you’ve been keeping up, you will know that ERC-721 is the protocol used by the majority of NFTs on the Ethereum blockchain. Essentially, picking “ERC-721” is a way of saying “NFT,” while trying to seem slightly less obvious. But it’s needlessly specific and confusing, in a way that doesn’t really represent the year’s conversation (ERC-721 doesn’t enable resale royalties, wasn’t around when artists like Kevin McCoy innovated the ideas behind NFTs, and doesn’t apply to non-Ethereum platforms like Hic et Nunc that also captured a lot of artists’ imagination this year).

It would have been cleaner and clearer to just be basic and say “NFTs.”

In any case, the logic of the Power 100 only gets stranger as you go down the list. The Second Most Powerful Person in the art world is… Anna L. Tsing? If you don’t know who that is, she’s not really an art-specific figure. She’s an anthropologist and author of the Mushroom at the End of the World.

She seems interesting… but powerful? Like, “non-human entity” powerful? Feels wrong.

Members of the art collective ruangrupa release the Documenta artist list in the pages of the magazine Asphalt”. (Photo by Uwe Zucchi/picture alliance via Getty Images)

At #3 is the collective known as ruangrupa, whose role curating the upcoming Documenta has won it a place in the Power 100 for several years running now. But, bad news for ruangrupa: We are informed that they have dropped one place, to #3 from last year’s #2. In 2021, the anticipation of their upcoming role as Documenta curators was no match for the unstoppable Anna L. Tsing juggernaut.

And so it goes, down the Power 100.

The late David Graeber and his collaborator David Wengrow are at #10 for a book, The History of Everything, that is not about art and was only published in October 2021! Another thinker, University of Westminster-based writer-curator May Adadol Ingawanij is #62. She is noted for being the author of a book that hasn’t even been published yet, Animistic Medium: Contemporary Southeast Asian Artists.

What is this? A Fantasy Football draft for catalogue footnotes?

Entrepreneurs Cameron Winklevoss and Tyler Winklevoss discuss, investors in Nifty Gateway, appear at FOX Studios on December 11, 2017 in New York City. (Photo by Astrid Stawiarz/Getty Images)

But then there are also people like the Winklevoss Twins, who are investors in the NFT platform Nifty Gateway (at #58), and crowd-pleasers like KAWS (#29), and a scattering of familiar power dealers like the mighty David Zwirner (#23)—whose star has fallen tragically since his 2018 heyday, when he was ArtReview’s Most Powerful Person himself.

I know that this list, like all lists, is not science. It’s an editorial attention-getter. But the list itself pretends otherwise. It even represents the rise and fall of power via arrows, solemnly indicating how many points up or down different people have gone from year to year. (Should I be alarmed that Black Lives Matter, named by ArtReview as the Most Powerful Person from 2020, has completely vanished from this list, alongside the #MeToo Movement, which was #4?)

Explaining the thinking behind the 2021 Power 100, ArtReview itself insists that it a hard-nosed analytical exercise—while also seeming pretty confused about the whole thing:

Observing and parsing power can be a means of understanding it, of seeing patterns. And not going by gut instinct or surface appearances. Although the artworld certainly relies on that. Which is also to say that this list is not about the magazine’s taste or likes, or personal positions, but rather about the artworld as a group of people with different tastes, positions and viewpoints see it, and how those disparate viewpoints sometimes intersect or meet. Or don’t. While trying to be as dispassionate and objective as possible. Even if most successful art does depend on passion and a degree of subjectivity. And you can make of all that what you will.

I understood the Power 100 better back when it really was just a ranking, “observing and parsing” art-industry players, with the top spots being mainly mega-gallery dealers, museum directors, star curators, and the occasional news-making artist.

But about 2017, when video artist Hito Steyerl was strangely named the Most Powerful Person in Art (she’s a more modest #17 this year), it started to become more and more incoherent. That coincided with the intense turn to social-justice rhetoric in the culture industries at large. “Power” became a less and less cool concept. The Power 100 seemed to have more and more difficulty getting its judges to rank who they thought actually was powerful rather than putting in figures who they wanted to champion.

Hito Steyerl. Photo: Brill/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

So you get a weirdly wishful picture of how power works. Referring (I think) to the ongoing Power 100 reign of philosophers like Fred Moten (#6) and Paul B. Preciado (#36), ArtReview writes, “if you read through this year’s list closely, you’ll find that theory, or thinking about what art is, what it’s for and what it can be, remains the glue that holds together the various pieces of what we once, quite casually, referred to as a global artworld.”

I do truly like the idea of thinkers having so much power. But I’d also like to speak all the languages of the world, and I can’t even transcend my gringo Spanish. If high-minded ideas had so much power to hold things together, the crypto-capitalists would not have upended the global art world so fast. The fact that the big auction houses—totally absent from the Power 100!—got on board with NFTs made the phenomenon impossible to ignore, turning it into a pop-culture force and changing the cultural landscape to such an extent that we all have to know what the unlovely string of characters “ERC-721” means.

That’s real power!

But there is good news here. All ninety-nine of the top picks on this list are deemed more powerful than Facebook boss turned metaverse-enthusiast Mark Zuckerberg, who comes in at a humble #100. With this kind of combined might, it shouldn’t be too hard for the art world to fix the internet. Let’s get Anne Imhoff, Miuccia Prada, and Hans Ulrich Obrist on it, stat.

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg arrives to testify before a combined Senate Judiciary and Commerce committee hearing in the Hart Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill April 10, 2018 in Washington, DC. Photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.

The 2021 CultureTrack survey has been released. If you are not the very specific kind of art wonk that knows what that is, it’s a yearly survey of the public from marketing firm LaPlaca Cohen that seeks to look at trends in the arts and how they are shaping culture, with suggestions for how museums might respond.

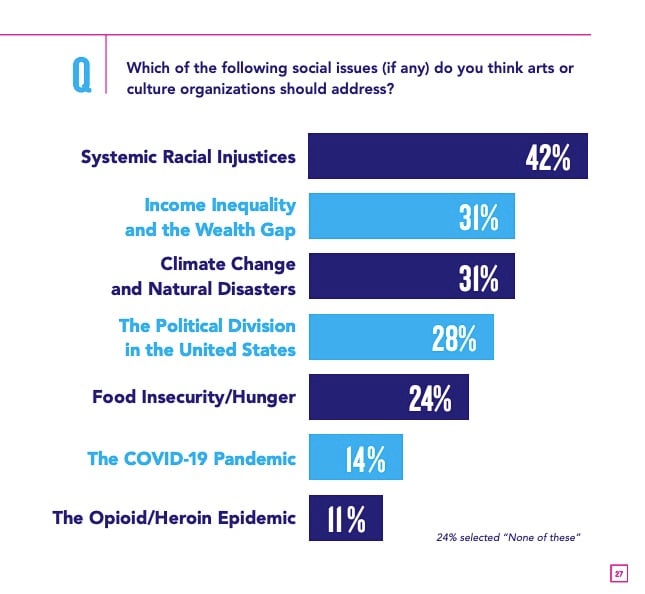

The study finds that, with the world in turmoil, audiences are feeling high levels of disconnection and sadness. It also asked, “Which of the following social issues (if any) do you think arts or culture organizations should address?” and offered a list of choices to pick from. Here were the results:

Graphic from CultureTrack’s 2021 survey.

It’s not totally clear what respondents—or the survey writers themselves, for that matter—thought “addressing” these issues might mean. I mean, how do you “address” a “Natural Disaster” at the museum level? Are we talking about storm-proofing the building, or putting up infographics on sea level rise, or doing an art fundraiser for hurricane relief? It could mean all of this or none of this.

The study’s authors interpret the results to mean that museums should explore becoming change-making advocacy organizations: “Arts organizations can serve communities by taking a stand on the issues they are best poised to address, collaborating with them along the way.”

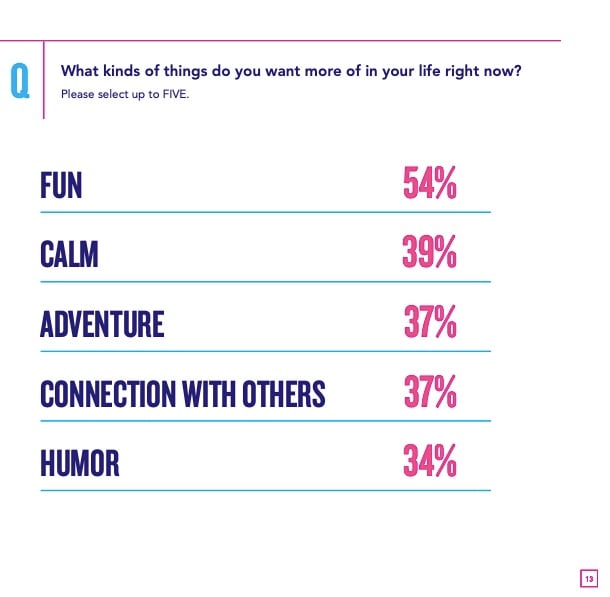

The confusing thing, though, is that “taking a stand” on the important issues of the day is actually not what the study finds that an audience wants from cultural activities at this particular moment in history. When asked by the survey, “What kinds of things do you want more of in your life right now?” some 54 percent say “Fun.” That’s the most resounding answer of any in the survey.

Graphic from CultureTrack’s 2021 survey.

(Another question here about online activities had similar results, with “Fun” being the top draw for culture online, with 49 percent. Last year’s CultureTrack survey found the same: “activities that are fun, lighthearted, and beautiful appeal most.”)

If I were interpreting the results, I wouldn’t read them as any kind of clear mandate. I’d more say, “wow, what a confusing time for museums. On the one hand, the audience wants Meow Wolf; on the other hand, it wants the CHOP.”

From Miami, my colleague Tim Schneider sends me some great stuff from the gift shop of Superblue, the Pace-affiliated experience-art factory whose big ambitions to expand art extend, evidentially, to the merch.

A Superblue Christmas tree ornament at the Superblue gift shop. Photo by Tim Schneider.

There, you can get your hands on Superblue drink coasters, Superblue flasks, Superblue throw pillows, and Superblue Christmas tree ornaments. Plus, an assortment of Superblue-appropriate scented candles. Clearly, this new multi-sensory model of art opens up whole new horizons for souvenirs.

But the pièce de résistance has to be this Superblue tea infuser. That is truly “immersive art.”

A Superblue tea infuser at the Superblue gift shop. Photo by Tim Schneider.