Opinion

A Masterful Charles White Painting Could Smash the Artist’s Auction Record, But Let’s Not Forget That He Was Devoted to Making Art for the Masses

The painting could fetch $1.5 million when it sells at Christie's New York this month.

The painting could fetch $1.5 million when it sells at Christie's New York this month.

Eddie Chambers

One of the key points that Barbara Jones-Hogu made in her 1973 manifesto for the influential group that went by the unforgettable name African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists Work (or AFRI-COBRA for short) was that black artists should ensure that their work was accessible to their audiences. She didn’t just mean what artists drew, printed, painted or sculpted; she also meant artists ensuring that their work, or reproductions of it, were within easy reach of the people with whom it was intended to dialogue.

Jones-Hogu stressed the importance of “modes of expression, that lend themselves to economical mass production techniques such as ‘Poster Art’ so that everyone who wants one can have one.” Jones-Hogu may well have been mindful of the strategies of audience engagement pioneered by the renowned American artist Charles White, whose work is becoming ever more celebrated, as two current exhibitions on the campus of the University of Texas at Austin—at the Blanton Museum of Art and the Christian-Green Gallery—attest.

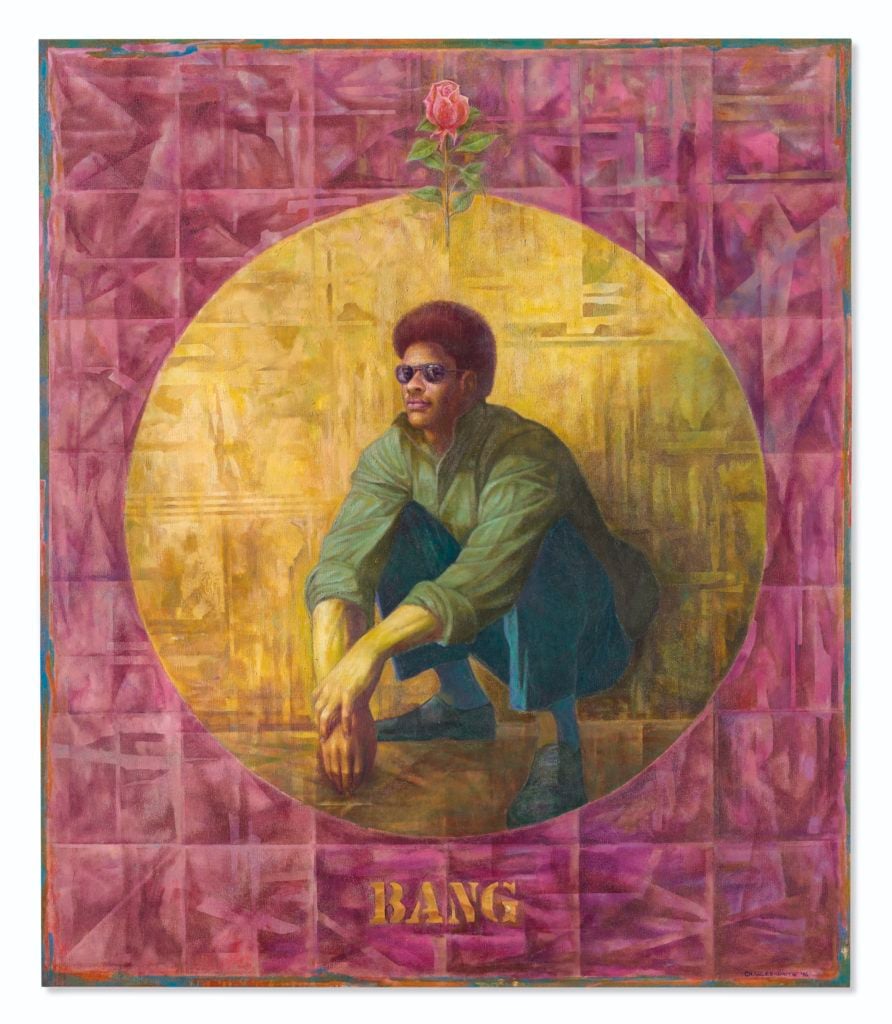

Relatively speaking, White’s work has consistently achieved respectable prices at auction. How could they not? With his work widely reproduced in print, and featuring in so many published or exhibited histories of African American art, the chance to own a Charles White original is something many collectors are keen to do. Even so, this month’s auction at Christie’s New York of one of the artist’s lesser known works, Banner for Willie J., a 1976 oil painting, will be something of a milestone, because the work carries an estimate of between $1 million and $1.5 million.

No doubt the escalation in appreciation of White’s work, in part a consequence of his major exhibition that traveled from Chicago to New York to Los Angeles, has helped increase valuations of his originals, but we still might be tempted to think that such financial appraisals are overdue. Banner for Willie J. is a beautiful, hugely engaging work, instantly recognizable as coming from the artist’s mid-1970s period, and it’s a work that has wider stylistic similarities with Homage to Sterling Brown, produced a few years earlier. Both have a lyricism, a deep affection for the black male figure, and White’s characteristic attachment to depicting human anatomy. The price that Banner for Willie J. might realize could significantly exceed the handsome prices his work has already been achieving at auction in recent years.

Charles White, Banner for Willie J. (1976). Courtesy of Christie’s Images, Ltd.

Yet we shouldn’t let the excitement over this high-profile work obscure one the most salient aspects of White’s practice: that he was steadfastly committed to making art accessible to all, a pursuit he achieved by mass-producing his images on book jackets, record sleeves, and other printed materials.

Born in Chicago in 1918, White, who died at the relatively young age of 61, was a highly accomplished draughtsman, painter, printmaker, and muralist. He dedicated his life to his art, which was characterized by his commitment to depicting African Americans as dignified, resilient survivors, and to this end, his drawings of black Americans resonated with hope, fortitude, humanity, and pride.

With a highly distinctive drawing style, White’s recent exhibitions have firmly, though belatedly, established him as one of the most respected and admired American artists of the 20th century. His drawings, though in some respects hugely accessible, were nuanced creations embodying many layers of meaning, history, and culture. One of White’s strategies was to produce folios of reproductions of his drawings, and he saw to it that at least six different folios were brought into existence over the course of a career cut short by illness. These folios attested to his determination to see his work brought within reach of those who could ill afford gallery prices and may well have been somewhat alienated from the world of art galleries and museums.

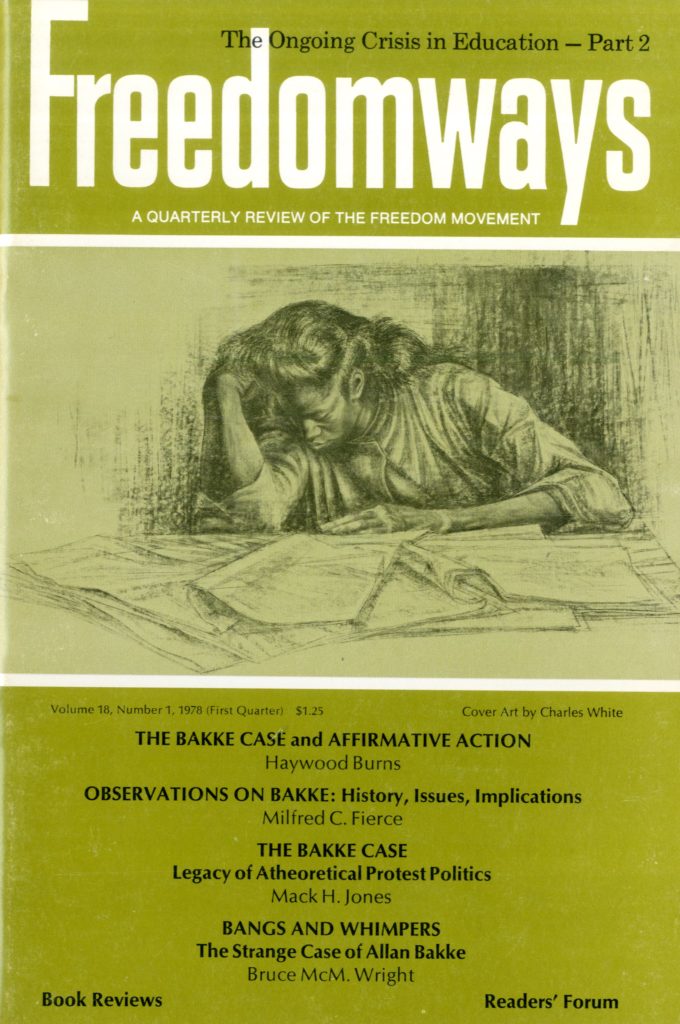

Charles White’s Awaken from the Unknowing (1961) on the cover of Freedomways journal, “a quarterly review of the freedom movement.” Collection of Eddie Chambers.

The first of these folios was issued in 1953 and contained reproductions of what were already widely regarded as classic works by White. Remarkably, the folio cost a mere $3, which even in today’s money is somewhere in the region of just $30. The other folios, published over the next couple of decades, were similarly modestly priced. It is, however, White’s prolific work as an illustrator of record sleeves, book jackets, and so on that is perhaps the least remembered or appreciated aspect of his work, even though such reproductions were the means through which many African Americans came to know and love the artist. Poet Nikki Giovanni perfectly expressed the affection many people have for White’s images, in her poem named for the artist: “Charles White and his art were introduced to me through magazines and books—that’s why I love them.”

No other artist lent more reproductions of their work to book jackets, magazine covers, and record sleeves than White. With their potency, articulation, and awesome visual beauty they are an absolute pleasure to behold. Given White’s particular appreciation of black culture in its many forms, including black American music, his evocative, poetic drawings were perfect for the sleeves of the jazz records they frequently came to adorn. Make no mistake, these were beautifully crafted images that not only functioned perfectly as distinct drawings (at a time when photography and graphic design were increasingly being deployed in the service of record sleeve illustration), but also managed to directly dialogue with the music of the records themselves.

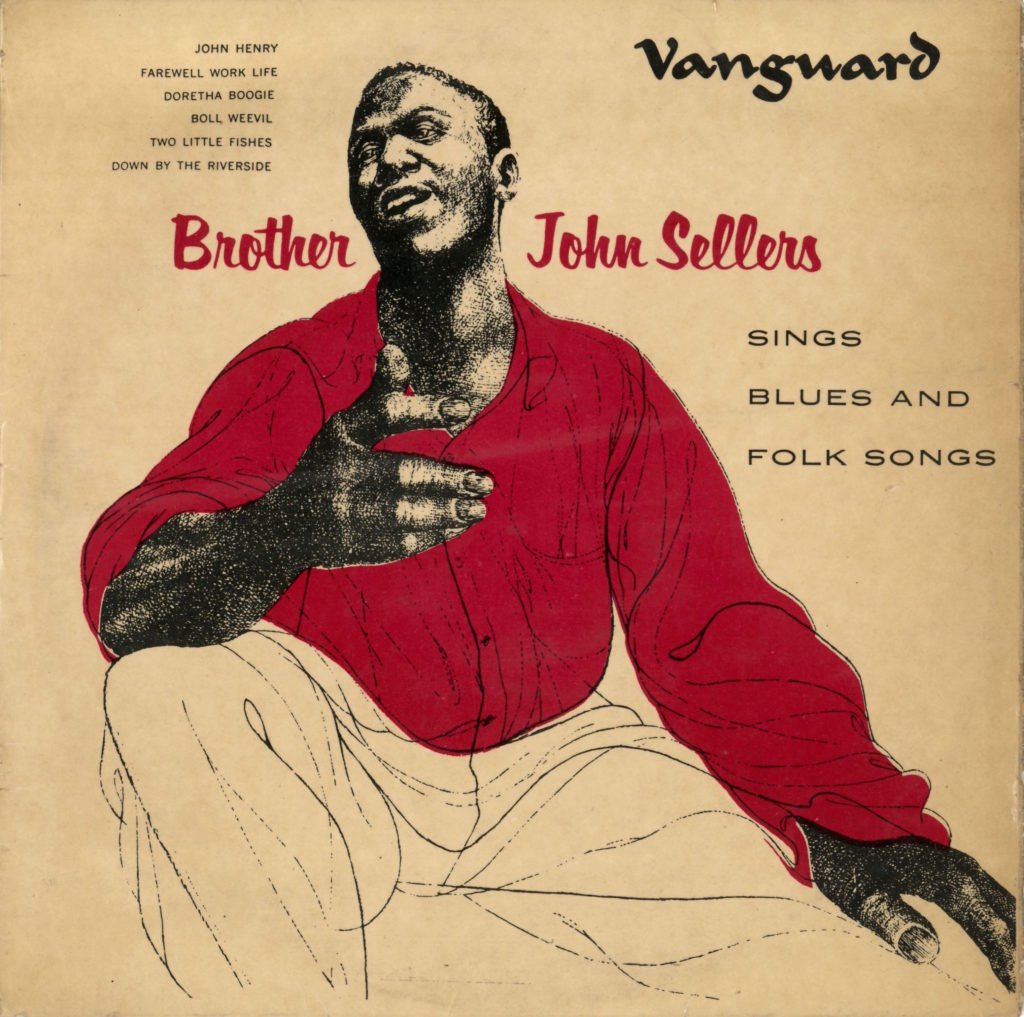

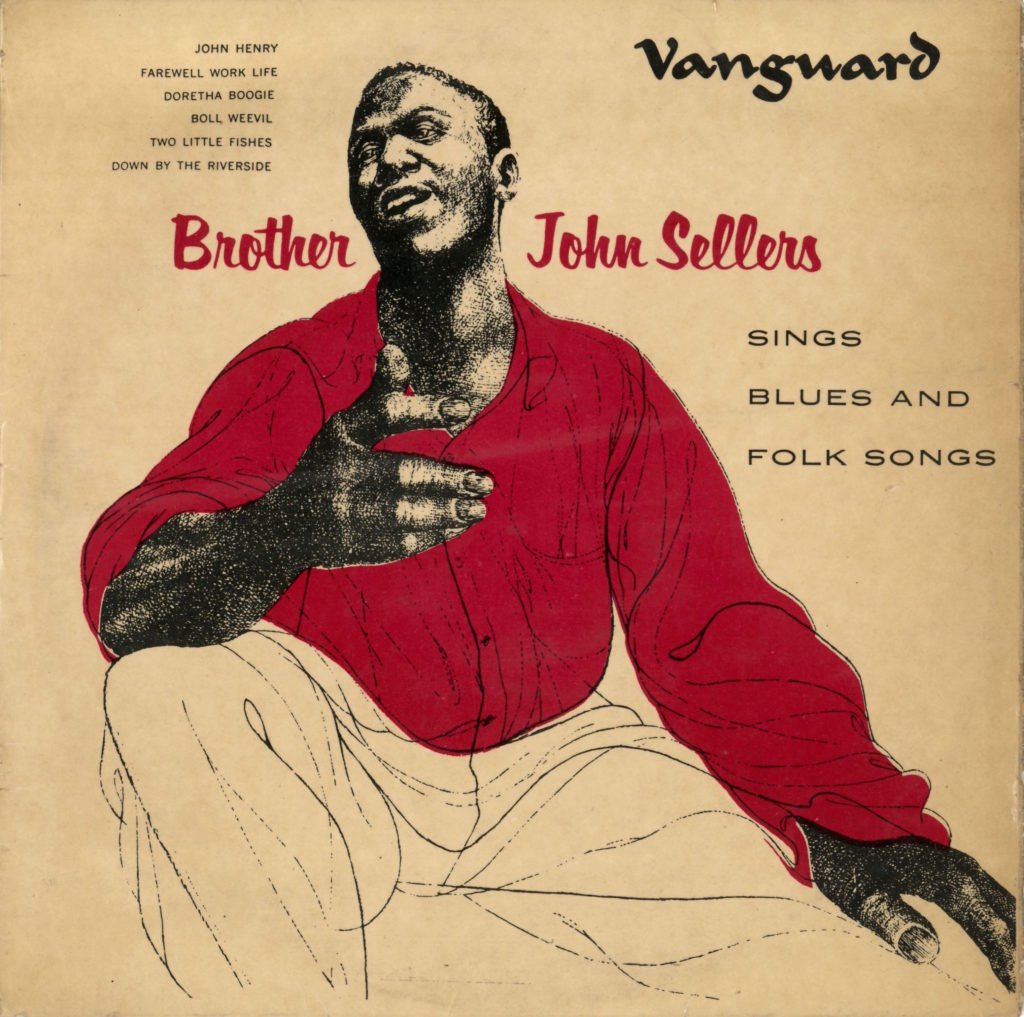

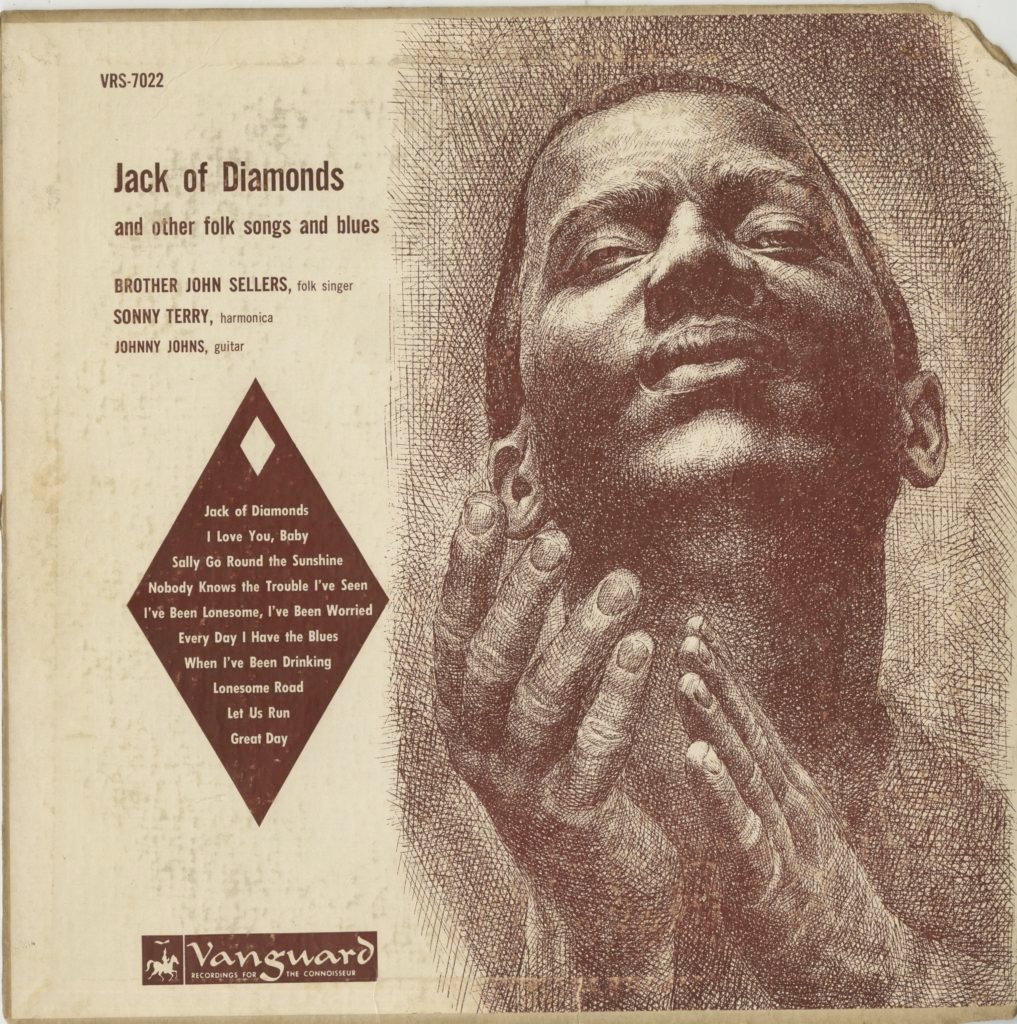

White supplied drawings for a number of Vanguard label records, for the most part with 10-inch sleeves. Now, in 2019, seeing the record sleeves of these jazz and blues recordings we can appreciate just how wonderful a draughtsman White was, and just how committed he was to bringing his work to wider audiences. Though White’s work gained widespread appreciation from the 1940s onwards, he took time during his particularly productive mid-20th century years to undertake these record sleeve commissions.

Drawing by Charles White on the cover of Brother John Sellers, Jack of Diamonds (ca. 1954) record. Collection of Eddie Chambers.

Not infrequently, his successes as an artist were noted on the backs of the record sleeves he had illustrated, with words such as:

“The drawing on the cover is one of a series commissioned by Vanguard Recording Society, Inc., from the distinguished American artist, Charles White, for use on its Jazz Showcase and classical releases. Aside from our belief that it takes a creative artist to capture the full human feeling of creative music, we hope by this means to bring to the public a knowledge of contemporary American art such as this, which has only to be seen to be loved. Charles White won the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1942, an Academy of Arts and Letters Award in 1952, and a National Prize of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. His work is represented in the Whitney Museum, Library of Congress, and other famous collections.”

Like White’s art itself, his record sleeve illustrations were every bit as committed to portraying African Americans as dignified and resilient, with his images resonating with hope, fortitude, humanity, and culture. And because what I refer to as White’s 10- and 12-inch messages came directly into people’s homes, individuals could appreciate the crosshatching, exquisite draughtsmanship, and perfect compositions of his drawings, without having to stand behind a gallery barrier, or be separated from a drawing or print by glazing. Within the Charles White exhibitions on the University of Texas at Austin campus, seeing a work such as Awaken from the Unknowing (a drawing of a young African American woman, studying, her copious papers spread across the table at which she reads) and, a short distance away, being able to see the same drawing, reproduced in miniature, on the cover of Freedomways journal is indeed a special experience in which a remarkable dialogue is created between the two images, one an original, the other a much smaller reproduction.

Would that more artists of the present time had such a singular, broad-based commitment to sharing their work with multiple audiences. It is perhaps extraordinary that such a dynamic aspect of White’s practice has received relatively little scholarship. Perhaps that will change.

Professor Eddie Chambers joined the department of art and art history at the University of Texas at Austin in 2010, teaching African Diaspora art history. He is the editor of the forthcoming Routledge Companion to African American Art History.