Art Criticism

Pace Gave Its New Digital Director Christiana Ine-Kimba Boyle the Keys to Its Brick and Mortar Gallery. The Results Are Refreshing

“Convergent Evolutions" is elegantly radical in how it opens up new conversations around its artists.

“Convergent Evolutions" is elegantly radical in how it opens up new conversations around its artists.

Folasade Ologundudu

In “Convergent Evolutions: The Conscious of Body Work,” Christiana Ine-Kimba Boyle brings together the work of 17 Pace and non-Pace artists in an exuberant show that’s all about asserting agency over oneself in image-making. Through her curation, Ine-Kimba Boyle, the newly appointed online sales director at the gallery, draws parallels between seemingly divergent artists, uniting practices that resonate unexpectedly across time and space, culture and creed, race and gender, and abstraction and figuration.

Artists as distinct as Anthony Akinbola, Caitlin Cherry, Sam Gilliam, Sonia Gomes, Anna Park, Lucas Samaras, Chibuike Uzoma, and Rachel Eulena Williams speak to each other in Ine-Kimba Boyle’s captivating arrangement. “Working at Pace has given me access to an incredible roster of artists that span various periods and mediums,” Ine-Kimba Boyle shared in an email. ”I felt a calling to expand on my prior work and research within an intergenerational lens, focusing on how so many artists of different backgrounds and practices have been navigating the topic of image-making through their work in different ways.”

Ine-Kimba Boyle’s curatorial premise draws on multiple sources: the rich archive of Pace artists, a plethora of young emerging talent, and books like bell hooks’s Art on My Mind: Visual Politics and Legacy Russell’s recent Glitch Feminism. Joining Pace in May after the highly successful “Black Femme: Sovereign of WAP and the Virtual Realm” at Canada gallery, where she was senior director of sales, Ine-Kimba Boyle has brought her innovative approach to the powerhouse gallery. “A large part of what attracted me was the more than 50-year reputation Pace has built,” she explained. “I also felt a responsibility to occupy space as a young first-generation African American woman within a position that unifies both the tech and art worlds—industries that still have strides to make regarding diversity and representation.”

Installation view of “Convergent Evolutions: The Conscious of Body Work.” Photo courtesy Pace Gallery.

Ine-Kimba Boyle’s path to this new role began decades earlier at a small magnet school in Yonkers, New York, just blocks from the Hudson River Museum. There, immersive research-based programs in art and science fueled her creativity. High school and early college internships—starting with the American Folk Art Museum and later the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where she worked as a teen docent during summer months—piqued her interest in pursuing a career in the arts.

Further internships at C24, Paddle8, and finally Gagosian proved formative, with Ine-Kimba Boyle learning the ins and outs of the commercial side of art sales. Her first, at C24, came from applying cold on Craigslist, and Ine-Kimba Boyle’s story reminds me of how difficult it can be to land coveted roles without access to resources or connections.

“The majority of the people I was working with were either the children of collectors or individuals that had access,” she recalled. “They were from a different setting than I was coming from. I was a kid literally raised by a single mom from the Bronx.”

As someone not from an art-collecting family or armed with the personal and professional resources that come via nepotism, Ine-Kimba Boyle understood that her presence was radical in and of itself. At Gagosian, the director recalled, “I made it very clear that I was there to work and I had something to offer. It’s always been important to me to make sure that I push forward.”

Her love for abstraction, an important presence in “Convergent Evolutions,” began at her first gallery job out of college, at the now-closed Loretta Howard gallery in Chelsea. Discovering influential abstract painters represented by the gallery, such as Larry Poons and Helen Frankenthaler, left a lasting impression on her.

Installation view of “Convergent Evolutions: The Conscious of Body Work.” Photo courtesy Pace Gallery.

“Convergent Evolutions” is not only a culmination of years of experiences. It’s a call to action, a challenge, and an opportunity to reframe the canon and how art is critiqued and interpreted—and by whom.

Much of what is explored in Ine-Kimba Boyle’s new show began with “Black Femme: Sovereign of WAP and the Virtual Realm,” which assembled Black female-identifying artists working to challenge and dismantle restrictive social standards imposed on the Black femme body.

Figures such as Caitlin Cherry and Delphine Desane are present in both shows. But in the Pace exhibition, Ine-Kimba Boyle explores image-making more broadly, irrespective of race, gender, age, or artistic medium.

An excerpt from bell hooks’s Art on My Mind: Visual Politics describes the challenges faced by Black artists and critics trying to be taken seriously as art-makers in an industry where the white male gaze looms large:

Sadly, conservative white artists and critics who control the cultural production of writing about art seem to have the greatest difficulty accepting that one can be critically aware of visual politics—the way race, gender, and class shape art practices (who makes art, how it sells, who values it, who writes about it) without abandoning a fierce commitment to aesthetics. Black artists and critics must continually confront an art world so rooted in a politics of white-supremacist capitalist patriarchal exclusion that our relationship to art and aesthetics can be submerged by the effort to challenge and change this existing structure.

How can one find links among artists who have never been discussed or critiqued together, heeding hooks’s demand for a “fierce commitment to aesthetics”? As a curator, Ine-Kimba Boyle draws out connections that expand the framework for the artworks in the show. She writes:

There are countless similarities between many of the artists within the exhibition. In fact, the earliest onset of curation for the exhibition was inspired by my immediate connection between Caitlin Cherry and Lucas Samaras—initially rooted in the physical but then expanding beyond that, as both artists’ practices heavily delve into conversations around photo manipulation and the body rendered within the optical lens. Also, Rachel Eulena Williams, in conversation with Sam Gilliam and Sonia Gomes, speaking to these artists’ investigations of memorializing the body’s physicality within abstract gesture and form. Anthony Akinbola and Richard Pousette-Dart are tied through the psychology of perception and the phenomenology of the somatic. Delphine Desane and Marina Perez Simão are connected by abstract figuration and landscape. Jo Baer and Kylie Manning are tied together by abstract figuration as well.

Installation view of “Convergent Evolutions: The Conscious of Body Work.” Photo courtesy Pace Gallery.

A number of the emerging artists whose work is presented in the exhibition commented on how Ine-Kimba Boyle’s curation built new conversations around their image-making.

Anthony Akinbola, a Nigerian-American interdisciplinary artist, has recently emerged as a vital presence in a new wave of young Black artists working in abstraction. His practice involves using “the du-rag as a tool for abstraction and deeper conversations around identity and accessibility,” he explained. Yet despite this unique contemporary symbolic language, he welcomed the way that “Convergent Evolutions” served to “evolve the conversation,” creating a dialogue with figures like Pousette-Dart and Gilliam.

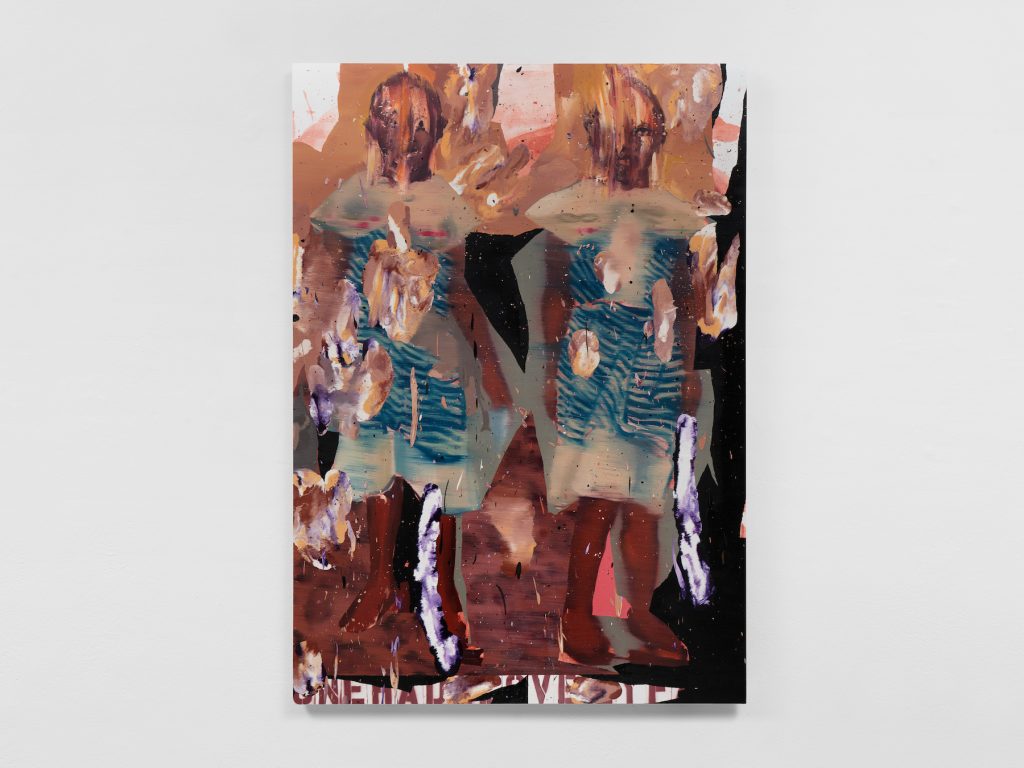

Kylie Manning, Squall (2021). © Kylie Manning, courtesy anonymous gallery and Pace Gallery.

Kylie Manning’s large-scale oil paintings vibrate with tension, with gestural marks at once intimate and idly detached. A native Alaskan and graduate of Mount Holyoke College (with a double major in philosophy and visual arts), Manning has three works in the show. She explained that Ine-Kimba Boyle’s vision is what drew her. “We both trust the viewer’s ability to dig a little deeper and understand that the friction they may feel in front of my work is the product of years of deep research,” she explained. “My continued research in the studio deals with breaking the conditions of narrative and unsettling what is assumed in contemporary figuration.”

RJ Messineo’s abstract paintings address “contemporary problems of representation” through observation and material. The Brooklyn-based artist, a graduate of UCLA and Cornell, said that Ine-Kimba Boyle focus on intergenerational interactions felt liberating. “Her thinking along the lines of bringing divergent works together and then walking out of the room really shows and honors the experience of receivership,” Messineo said. “It feels a bit subversive.”

The only artist whose work is displayed in a private room—intentionally separated from the rest of the show—is Nigeria-born Chibuike Uzoma, a recent Yale grad. The installation device puts a particular spotlight on the work, which in fact must be viewed through a glass window.

Chibuike Uzoma, One Had A Lovely Face (2020). © Chibuike Uzoma, courtesy the artist and Pace Gallery.

“Sometimes we simply have to place things at a distance to see them,” Uzoma reflected in an email. “It is in that sense that I relate to how Ine-Kimba Boyle has intuitively placed the paintings in the exhibition… there is a well-measured distance between the painting and the audience, which I believe is useful for looking, wondering, and thinking.”

The brilliance of “Convergent Evolutions”—and it cannot be overstated—lies in the poignant ways in which she forces the viewer and the critic to find connections among artists who vary greatly in their artistic practice, but also more importantly in the signifiers that have been used to define them: ‘Black’ or ‘White’, ‘Rich’ or ‘Poor’, ‘Educated’ or ‘Uneducated’, ‘Man’ or ‘Woman.’ The same binaries being challenged in today’s society are being explored through this elegantly radical exhibition.

Installation view of “Convergent Evolutions: The Conscious of Body Work.” Photo courtesy Pace Gallery.

Ine-Kimba Boyle’s first show at Pace implores audiences to rethink their perceptions, creating space to envision a future in which artists are freed from the kinds of limiting frameworks that critics have imposed in the past. Perhaps this act might spark newer and more nuanced conversations about the power we possess to reframe the ways in which we are seen, heard, and ultimately understood.

“Convergent Evolutions: The Conscious of Body Work” is on view at New York’s Pace Gallery, 510 West 25th Street, September 10– October 23, 2021.