Curiosities

What If the ‘Birds Aren’t Real’ Movement Backfires? + More Questions I Have About the Week’s Art News

Also, are we in an Indie Aesthetics boom?

Also, are we in an Indie Aesthetics boom?

Ben Davis

Curiosities is a column where I comment on the art news of the week, sometimes about stories that were too small or strange to make the cut, sometimes just giving my thoughts on the highs and lows.

Below, some questions posed by the events of the last week…

I was gripped by Taylor Lorenz’s piece in the New York Times this week about the “Birds Aren’t Real” movement, a QAnon-era Gen Z effort at “culture jamming.” Online and in a series of real-life protests, partisans have set out to foment the message that “Birds Aren’t Real,” arguing that what look like harmless avian creatures are actually government surveillance drones.

It’s all an attempt to fight the fire of social-media zaniness with the fire of more social-media zaniness, in this case, funny stunts. Birds Aren’t Real seeks to introduce enough nonsense into the culture that people imbibing other, more menacing forms of cultural nonsense start to question what they read and are shocked to their senses.

I do generally agree with the artist and researcher Joshua Citarella, quoted in Lorenz’s piece, that the danger of such tactics is probably outweighed by the good of giving a cultural community a mission to band around, and offering people idle on the internet a positive outlet for their creative energies. “Allowing people to engage in collaborative world building is therapeutic because it lets them disarm conspiracism and engage in a safe way,” Citarella said.

But—not to be a wet blanket—I do think the likelihood that anti-bird ideology will turn the tide in the absence of some larger reversal in the decay in U.S. institutions is zero, and the possibility that they will in some way add to the chaos is, in some real way, non-zero. I mean, not just some but a substantial number of the core elements of modern conspiracy began as Birds Aren’t Real-esque attempts at info-warfare by artists. In some ways, this may be one of big impacts of art on politics.

To take a ready-to-hand example, recently highlighted in Adam Curtis’s despairing documentary, Can’t Get You Out of My Head: The entire modern obsession with the Bavarian Illuminati began in the 1960s, as what has been called a “free-form art project–cum–prank–cum–political protest.”

Kerry Thornley and Greg Hill created the fake religion Discordianism as a mockery of religions, which in turn birthed Operation Mindfuck, planting claims about a secret, history-controlling cabal in the letters section of Playboy and in the underground press, meant to be so outrageous and incoherent that it made similar claims bogus by association.

But instead, the idea of Illuminati control became part of the culture, mushrooming on the internet into conspiracy theory common sense.

What I’m saying is, it’s not impossible that sometime soon, some yoga cult in California will be banning Pigeon and Crow pose because Birds Aren’t Real, or that “Get These Government Birds Off My Lawn” could end up as a plank of the Republican party.

Last week, Google dropped its annual “Year in Search,” which is always good for a quick peep to see how more or less out of touch you are with the Googling masses.

It turns out that “NBA” was the most searched general interest term in the U.S.A. Coulda fooled me! The biggest news story of the year was “Mega Millions,” another one that left no trace in my world. Still, Olivia Rodrigo’s “driver’s license” was the Most-Searched Song of 2021. That I get.

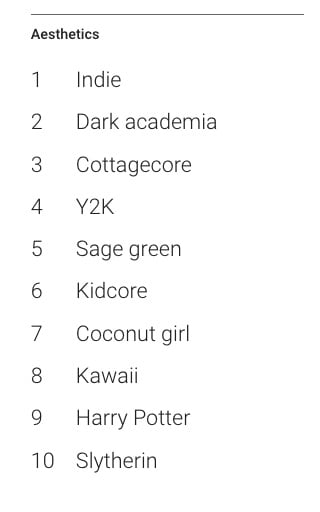

The thing that caught my eye, however, was that this year, among its trends, Google includes a list of Most-Searched “Aesthetics.”

This use of “aesthetic” has less to do with Kant’s Third Critique and more to do with an amorphous lifestyle sensibility emerging from fashion mags and interior design blogs. I read in a fascinating Vox article about “historic microaesthetics whisperer” Melinda Bee that naming trends has become something of a competitive sport on TikTok, as niche styles shoot out like sparks from the overheating engine of culture.

Here’s the Google’s view of the 2021 “Aesthetic” universe:

Screenshot of Google Trends for Most-Searched Aesthetics of 2021.

“Indie” sounds generic to me. I guess the story here is the backlash to the so-called “Millennial Aesthetic” that peaked immediately pre-pandemic: all affirming pastels, soft corners, cutesy blobform designs, and cloying empowerment sentiment (the Casper mattress ad look, if you recall that art-history landmark).

So, the new “Indie” look is a return to the low-fi, the edgy, and the disaffected, and cool colors. And also, it seems to be a nostalgia for things that happened about 10 years ago when there still was a hipster sensibility, but now even more queer and more diverse.

I popped over to the NADA art fair website, where the really new art hangs out, to see whether there was any “New Indie” vibe going at the just-finished Miami 2021. Maybe these bohemian figures posed in funky interiors, looking unmoored, from a painter like Polina Basrkaya do something like that?

And Claudia Keep’s paintings at March and TOPS Gallery booth, also at NADA, of bereft Brooklyn bedroom interiors? I’ve read it said that empty bedrooms are very “Indie.”

I see that there was chatter about a sub-trend within the “Indie” trend in 2021: “Indie Sleaze.” That’s sort of like the high-hipster, Dash Snow Vice-era look. (Whatdoyouknow, there was also a Dash Snow doc this year.)

Maybe you can think of something like Aryo Toh Djojo’s painting at Stems Gallery, which has that Vice sensibility sometimes. In fact, at NADA, he had a canvas called Miami Vice (2021), a palm tree framed against a sunset with the words “BANG BROS” in spidery raised type at the center—a subtle but hard-hitting commentary on the shadow cast by the Miami-based adult film company of the same name.

Or from a more femme direction, there’s Brittany Shepherd at in lieu gallery, who explores “niche fetish communities” and whose images of high heels hearken to Marilyn Minter’s grit-and-glam photorealism.

But I dunno—a lot of this seems just like the “NADA Look,” NADA being the most indie fair that is not actually called Independent. In any case, I can’t wait to see what the “Dark Academia” and “Coconut Girl” art movements might look like. I’ll be looking out for them!

Vintage souvenir postcard published circa 1937 depicting an exterior architectural view of the landmark Brooklyn Museum of Art. (Photo by Nextrecord Archives / Getty Images).

The Brooklyn Museum got a new COO and president this week: former Obama administration staffer and non-profit professional Kimberly Panicek Trueblood. Speaking to the New York Times, Trueblood was filled with mission. She is committed, she said, to “making sure the next 200 years are even more inclusive than the last 200.” I hope so!