Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, facing the music in more ways than one…

GEIGER COUNTER

On Wednesday, Marc Geiger, the former worldwide head of music for mega-agency WME, unveiled a plan to rescue dozens of struggling independent live-music venues across the US by acquiring them with a pool of like-minded investors. Geiger says the venture, called SaveLive, has raised $75 million in funding to date and is already in negotiations with “a number” of clubs in different regions. It also raises a grip of knotty questions about sustainability in the cultural economy before, during, and after the social-distancing era—all of which apply as urgently to small galleries as they do to small clubs.

Geiger has an impressive track record as a music-industry seer. In 1991, he co-founded Lollapalooza, the multi-day Chicago outdoor alternative-rock festival that set the modern template for the likes of Coachella and Bonnaroo. In 1996, he launched ArtistDirect, an ahead-of-its-time platform that the New York Times’s Ben Sisario describes as being premised on “the then-radical idea that artists should control their own online ‘channels’ of communication and commerce.” After ArtistDirect tanked in the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2000, Geiger returned to the game as an agent in 2003 and spent the next 17 years building himself back up into one of music’s unquestioned power brokers.

Notably, Geiger’s vision for SaveLive extends beyond the current prohibitions on mass gatherings. Once live music can return with gusto—a renaissance he doesn’t anticipate until at least 2022—he and his investors plan to connect the clubs in their portfolio into an indie touring network that could propel each of them to long-term success through economies of scale. It’s a strategy that recognizes the fundamentals of the business were unstable for small venues long before the country descended into a heated debate about the ethics of mask-wearing, even as the same venues remained a critical link in developing careers and advancing the art form. Sisario writes:

The night-after-night churn of club gigs is less lucrative and glamorous than the world of superstar arena tours. But it is a vital feeder for the entire industry, and clubs often inspire a passionate devotion that can be measured by the names and band logos scrawled on backstage walls.

Hmm, a for-profit culture sector where fresh artists grow their buzz and their paying audience by showcasing their work in progressively larger and more refined spaces, making the preservation of the pipeline’s early stages fundamental to the entire industry’s sustainability. Seems eerily familiar, no?

So could a scheme like SaveLive work for independent, modestly sized art dealers struggling to stay above water in the winner-takes-all 2020s? As usual, it’s complicated…

The exterior of legendary New York club CBGB in 2005. Photography by Stig Nygaard. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

X MARKS THE SPOT

To me, one important difference between small live-music venues and small galleries concerns real estate. Sure, it can be vital for owners of each to maintain a consistent brick-and-mortar presence. But setting aside the special alchemy between certain dealers’ physical premises, programs, and scenes for certain distinct stretches, galleries change locations within cities all the time without damaging their auras or sustainability.

In contrast, the specific spaces occupied by small clubs are vital to their identities. Even in the rare instances when an owner moves a beloved venue rather than closing it, the new spot can never quite be the same to the artists or the die-hard fans. For instance, you can practically feel the grimy romance of placeness seeping through the copy of New York Times pop-music critic Jon Pareles’s 2006 send-off of CBGB, the punk and post-punk cradle on the Bowery that nurtured acts like the Ramones, Talking Heads, Patti Smith, and Blondie:

In some ways CBGB, which opened in December 1973, ended its life as it had started. The club never moved from its initial location, which was originally under a Bowery flophouse, now a homeless shelter. It never changed its floor plan, with a long bar lighted by neon beer signs on the way to an uneven floor, a peeling ceiling, a peculiarly angled stage and notorious bathrooms. Through the years, the sound system was improved until its clean roar could make any power chord sound explosive. Mostly, however, CBGB just grew more encrusted: with dust, with band posters stuck on every available surface, with bodily fluids from performers and patrons.

This is why it was so sad for longtime New Yorkers and music heads everywhere to see CBGB turned into a John Varvatos boutique: the club’s soul could only really be conjured in one space.

In this sense at least, a SaveLive-like consortium of investors might actually be a friendlier proposition in the gallery sphere than in the music scene. What ultimately matters most to a gallery are the people involved. The greater optionality on real estate should prevent Geiger’s hypothetical gallery equivalent from being completely backed into a corner by the landlords of specific buildings in an increasingly unforgiving real estate market.

However, this advantage gives way to larger, more fundamental questions about the model—some of which loom just as large for SaveLive itself.

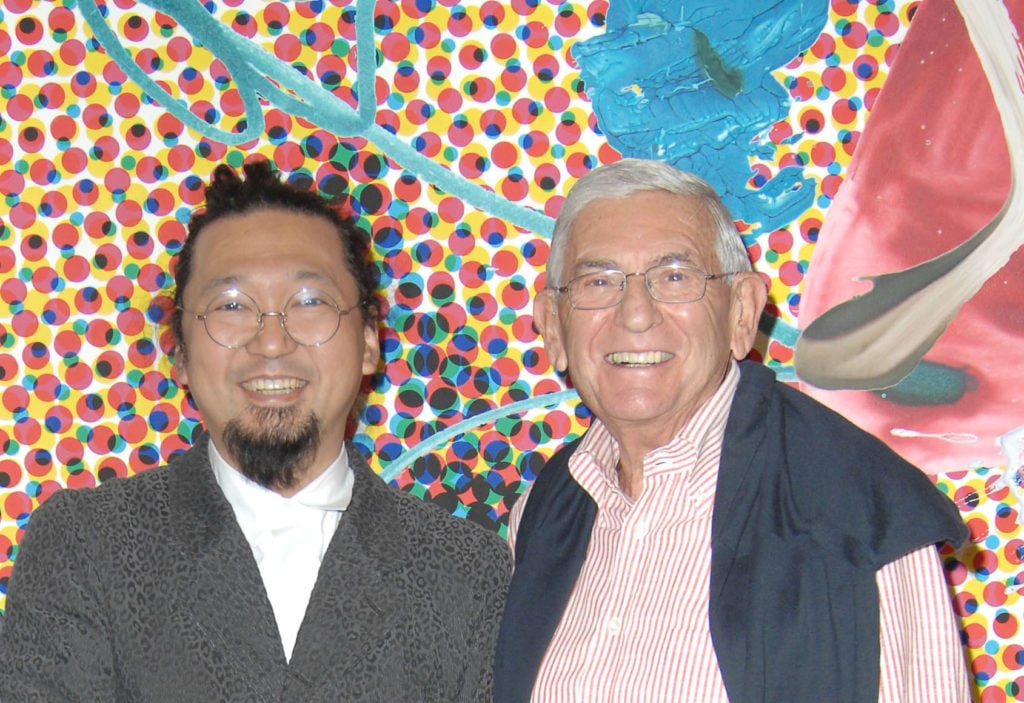

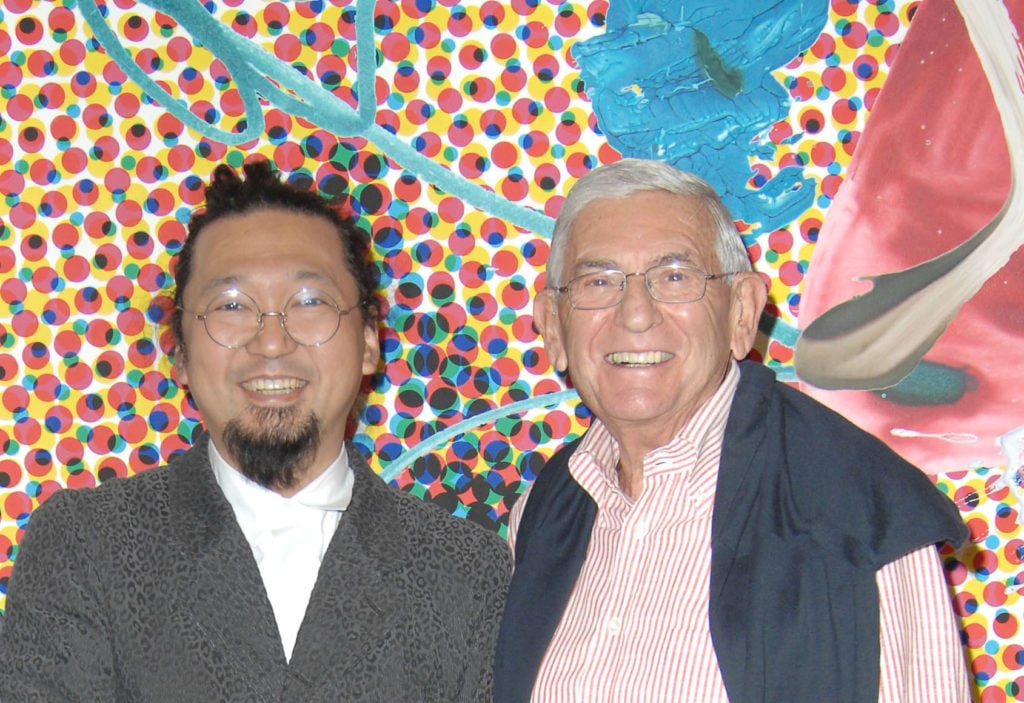

Takashi Murakami with Broad Museum cofounder and Los Angeles County Museum of Art lifetime trustee Eli Broad. Photo: DAVID CROTTY/patrickmcmullan.com

BAND OF OUTSIDERS

Foremost among my concerns in this thought exercise is the central dramatic tension between independent spirit and investor backing. In SaveLive, Geiger and his fellow money men are pointedly set on acquiring 51 percent stakes in all of the venture’s clubs. Although hedge-funder Jordan Moelis went on the record to assure skeptics that he and his fellow investors “don’t see [SaveLive] as a distressed-asset play,” the fact remains that they will become the venues’ controlling shareholders. Geiger also insists that the original owners will be treated as genuine “long-term partner[s],” but it’s always fair to be wary of that pledge when the party making it owns a large enough chunk of the enterprise to render everyone else’s opinions irrelevant.

For example, SaveLive says it wants to be profitable in four years. Will the minority partners stay on board with that timeline once they see the kinds of compromises or cuts that might be needed to get there? How sure can they be that the investors will always align with the booking choices they would have made independently? What will being bundled and rebranded into a network mean for the individual identities that led to their clubs’ popularity in the first place?

These same elemental questions would apply to a gallery-sector version of SaveLive, too. I especially wonder about the influence of the investors’ taste on the galleries’ programming. I can’t help but think about how, in an era of vanishing public funding, the programs of major US museums have increasingly absorbed the artists preferred by their trustees and prominent donors.

Even if the questions and potential conflicts of interest could be resolved to the satisfaction of all involved, though, the rest of Geiger’s model may still diverge too much from art economics to be viable without major changes.

SaveLive founder and former music executive Marc Geiger at Billboard’s Power 100 reception in 2014. (Photo by Amanda Edwards/WireImage)

WHEN THE MUSIC STOPS

As Sisario writes, “SaveLive would, to some degree, resemble a mom-and-pop version of Live Nation or AEG, the giant companies that now dominate the touring business.” By pooling resources, SaveLive could, for instance, offer better terms to artists than either the individual venues or possibly even some larger competitors, making it more appealing to buzzy but scrappy talent to tour all of these beloved clubs than alternatives.

But this is where the model’s potential for galleries starts to sputter. The work made by musical artists and the work made by visual artists plays by largely different economic rules. A rising band produces a collection of new songs, then monetizes it by touring the exact same new work to several different venues. And that’s great for everyone, because the work is intangible. Sure, fans can own recordings (although even ownership gets murky in the streaming economy), but they go to shows to have an experience—one that the artist more or less replicates over and over, night after night, until the tour ends.

This business model has no real analog in the tiers of the gallery sector that cry out for SaveLive-like support. (Superblue, the ticket-sales-driven experiential-art experiment led by Pace Gallery’s Marc Glimcher, operates far too high on the budget spectrum to warrant discussion here.) The closest parallel would be if, say, a painter created an exhibition of new canvases for a small but respected dealer on New York’s Lower East Side, then mounted the same show at galleries of roughly the same stature in Chicago, Dallas, and Los Angeles.

That might be fine for viewers in those different cities. But dealers only generate revenue by selling the objects themselves. So if the paintings are successful, some (maybe even all) of them will find buyers at the first venue. This means fewer (maybe even none!) of the works would be available to collectors at the next galleries on the “tour.” The only alternative in this example would be for the painter to produce enough new work for four separate exhibitions, which would be like a band creating a new album to debut at every new club on its schedule. It’s too much to ask.

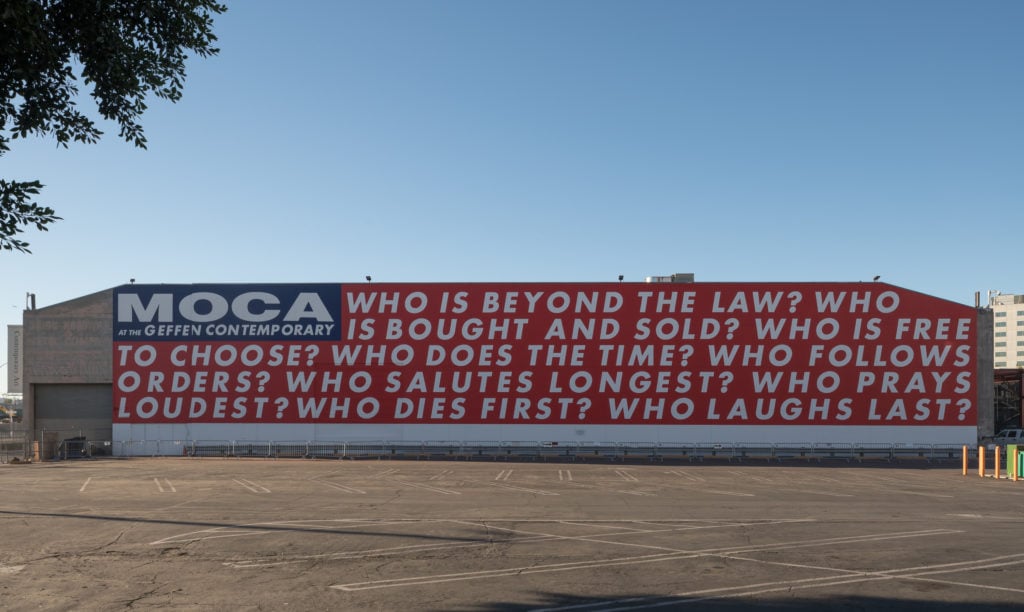

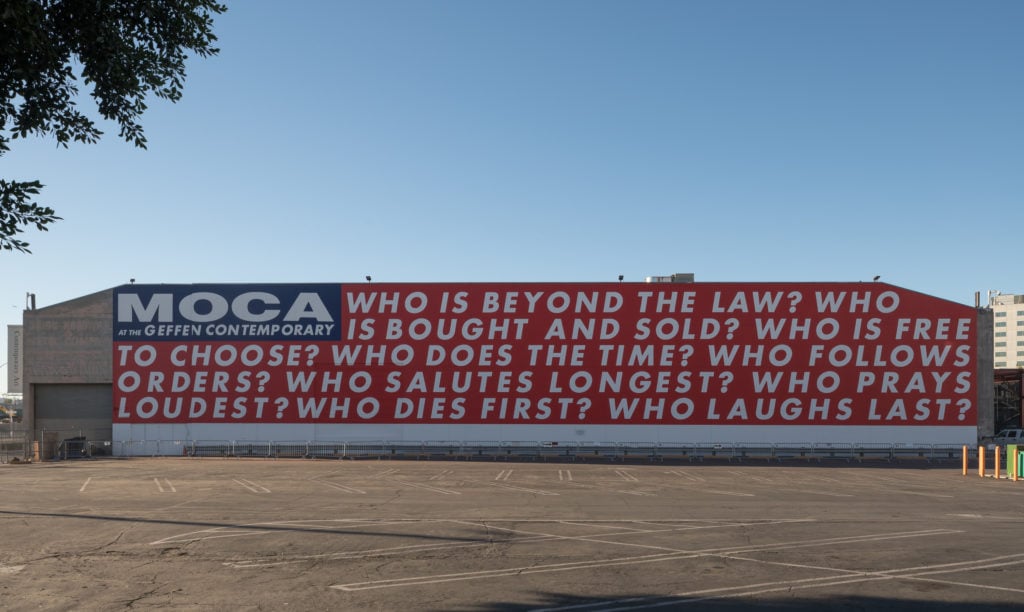

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Questions) (1990/2018). Photo by Elon Schoenholz, courtesy of MOCA.

The natural solution would be to split the dealer’s share of sales among all the galleries in the network. But at the price level we’re talking about here—let’s say works sold for $40,000 or less, with “less” being more the rule than the exception—and with half of the sales proceeds going to the artists, will there be enough profit to sustain the entire syndicate?

It’s possible that, with the backing of altruistic and largely hands-off investors, a network of galleries of the perfect size, geographical distribution, and taste profile, all constantly “touring” the right mix of hard-working artists, could make this delicate calculus balance out. But first the players involved would have to sort through a barrage of second-level issues essential to default expectations about how galleries work.

What would it mean to “represent” an artist in a network like SaveLive? Is it feasible to adapt every artist’s exhibition to the very different physical parameters of each gallery? Would every dealer be willing to share their respective contact lists and financials with the others to optimize decision-making by the group? What about hammering out a set of shared business practices to smooth the flow of information and artwork between galleries, as well as minimize cost and waste? Would there be penalties for breaking protocol? How would art fairs fit into the picture?

There may be answers to these questions and the dozens of others raised by the prospect of adapting SaveLive to the gallery world. It’s worth noting that at least a few of these challenges have been met by nascent collaborations between dealers including Gallery Association Los Angeles and the Brussels-based La Maison de Rendez-vous. Although these team-ups are miles of track away from the expertly crafted transcontinental talent railroad Geiger and his partners are hoping SaveLive will be, they reinforce that, now more than ever, independent proprietors of the arts must be willing to re-evaluate their most basic assumptions about how business is done if they want to outlast our current catastrophe. What clubs, galleries, and artists of all types will actually take away from these examples is their song to sing.

[The New York Times]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: what got you here probably won’t get you there.