Opinion

The Gray Market: Why America’s Art-World Shutdown Is Reaching a Breaking Point (and Other Insights)

Our columnist finds signs inside and outside the arts that social-distancing measures are losing traction—and raising impossible questions.

Our columnist finds signs inside and outside the arts that social-distancing measures are losing traction—and raising impossible questions.

Tim Schneider

Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, looking to the masses for guidance in our weird niche…

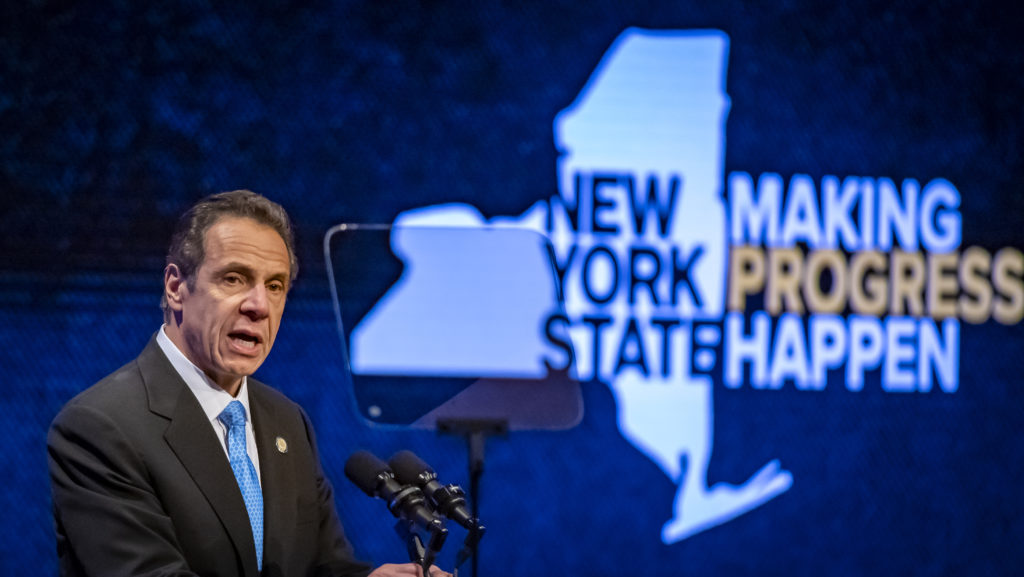

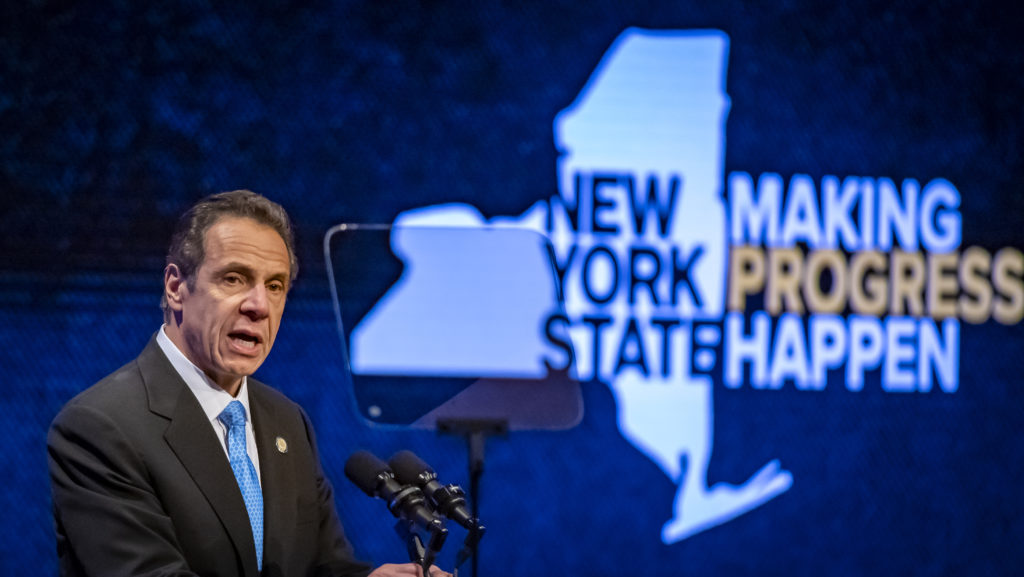

On Friday, the New York Times examined the tensions facing the upstate New York art institutions that will reopen first under governor Andrew Cuomo’s impending rollback of public-health restrictions. Yet data from elsewhere in the country suggests that these art centers’ efforts to reopen smoothly and safely will be undermined by out-of-towners desperate for a return to normal life. And the conflict epitomizes why business owners across the US, whether operating inside or outside the arts, will largely be placed in an impossible position as spring transitions into summer.

The crux of the initial dispute is Cuomo’s four-phase plan to reopen New York state’s economy, which has effectively been frozen for nearly two months. The good news for Dia:Beacon and other upstate art institutions is that the governor’s roadmap recognizes the vast differences in public-health statistics among the state’s 10 regions. So as long as the Hudson Valley, for example, manages to meet Cuomo’s various statistical benchmarks for hospitalization rates and related metrics, its businesses will be nudged out of hibernation regardless of New York City’s progress (or lack thereof).

The bad news? First, museums and other art institutions are currently grouped among the businesses that will only be permitted to reopen during the fourth and final phase of the recovery process. That places them alongside schools, gyms, and other centers for education and recreation—a categorization that doesn’t necessarily compute based on square footage or visitors’ activity within it.

But even if arts institutions succeed in lobbying the state for inclusion in an earlier phase of the economic thaw, as some are hoping to do, another danger looms. Here’s Julia Jacobs of the Times:

Arts administrators tend to be more reticent about opening up again if they risk that New Yorkers from downstate will travel north. Governor Cuomo has warned that arts venues will not be allowed to open if they draw significant numbers of people from outside the region, becoming what he termed “attractive nuisances.”

Side note: If there isn’t already a self-aware punk band forming somewhere in New York under the name Attractive Nuisances, my last shred of hope for the future will disintegrate.

That point aside, I think this stipulation spells trouble for upstate art centers, let alone their down-south cousins. And the reason is that we already have hard evidence that large numbers of people are ready to chuck extreme caution into the wood-chipper for the opportunity to reclaim a handful of the old normal.

Visitors in front of a work by Anish Kapoor. Photo courtesy of the High Museum of Art, Atlanta.

On Thursday, the Washington Post reported that Georgia, one of the first states to reopen non-essential businesses such as dine-in restaurants, hair salons, and gyms, welcomed nearly 550,000 out-of-state visitors in its first full week after liftings its lockdown. Using anonymized smartphone location-tracking data, researchers at the University of Maryland found the influx represented a 13 percent daily increase from the week preceding the state’s shutdown.

While there are caveats to the study, the results suggest that arts institutions in upstate New York are very likely to become exactly the kind of “attractive nuisances” that Cuomo warned against. Data showed that the vast majority of visitors to early-opening Georgia (92 percent, to be exact) came from neighboring states where the same types of businesses stayed largely or totally shuttered. And while the figures did not clock visitors’ specific destinations, researchers concluded that most inbound visitors came on “personal trips” rather than to return to work.

The reason for this last conclusion is noteworthy, too. Despite receiving permission from the governor’s office to resume normal operations, very few Georgia business owners actually chose to exercise that right. In fact, a separate study led by economist Raj Chetty found almost no difference in the number of small businesses open, the number of hours worked by small-business employees, and consumer spending in the weeks immediately before and after the shutdown’s declared end. The same held true not just in Georgia, but in all four states that lifted their commercial restrictions on or around April 24. (Alaska, Oklahoma, and South Carolina round out the quartet.)

Both of those findings reinforce my intuition that art enthusiasts living in downstate New York and the tristate area will indeed flock to the spacious, world-class institutions upstate as soon as possible. After all, they won’t have any other outlets besides the infinite scroll of artworks flattened onto backlit screens—and how many of them have been satisfied by that option since mid-March?

Yes, many cosmopolitan museums and commercial galleries are undoubtedly kicking and clawing at their closed front doors in anticipation of the day that it’s safe to responsibly welcome patrons again. But the research by Chetty and his team highlights an often-overlooked reality about this process: while “reopening the economy” is most often treated as a bureaucratic decision made entirely by the government, it actually requires private enterprise to agree with public officials about when the coast is clear enough to begin operating again.

And based on what we’re seeing inside and outside the art world, that is by no means a given here in the US.

Nam June Paik, Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii, 1995. Photo: Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

In every reference point I’ve included above, the common element is friction. Some upstate art institutions want to open sooner than Cuomo’s administration will currently allow. Meanwhile, Georgia’s governor wanted his state’s businesses to open sooner than most business owners could stomach— and thousands of would-be customers from neighboring states apparently agreed with the man making declarations from the safety of the governor’s mansion rather than the ones who would have to bear the health consequences if he’s wrong.

Who’s right in these situations? I have no idea! Unlike in Berlin, Seoul, and other foreign locales, where eager audiences have already materialized for appointment-based gallery viewings, the US’s amateurish public-health response means we still don’t know nearly enough about the threat itself to be able to identify the boundary between acceptable and unacceptable risks. This forces decision-makers at most US art institutions, commercial galleries, and non-art businesses to throw darts blindfolded.

The only thing I’m sure of is that we’re nearing a breaking point. After Deloitte released a somewhat unnerving report on Sotheby’s finances last week, CEO Charles Stewart seemed to play defense by emailing clients to tout the house’s online successes and pledge it is “actively preparing for the reopening of our galleries in New York and London.” Cuomo’s four-phase plan to reopen New York state would have to proceed almost flawlessly in the next seven weeks for that to happen in time for the marquee spring auctions now scheduled for late June… and it was not a great sign that the governor clarified over the weekend that he has the authority to push back phase one’s start date from May 15 to June 6, should conditions on the ground necessitate it.

If billionaire-owned Sotheby’s is feeling pressured to act, imagine how many independent small businesses must feel like the breath is being crushed out of their lungs. In fact, two galleries in California have already openly defied the state’s shutdown orders by reopening early (and one had to close again after repeated police warnings). The cracks are starting to show.

With financial losses mounting at nonprofit and for-private businesses, and the American unemployment rate reaching Great Depression levels, my sense is that desperation is prowling the streets on all sides. Buyers and sellers, museums and visitors, market observers and participants—nearly everyone without a vast cushion of wealth has been made vulnerable by the shutdown and its root cause.

Millions of people have proven willing to sacrifice for the sake of caution over the past several weeks. But with little strong reason to believe that a safe and controlled end is truly in sight, there is a point at which maintaining preventive measures becomes as untenable as the risks those measures are meant to mitigate.

When it comes to art, though, one person’s would-be escape is another person’s livelihood and wellbeing, and one governor’s decree is another business-owner’s bad advice to contradict. All of these forces are on a collision course, and no state official, medical expert, or industry analyst can tell you what will happen once they meet. But for better or worse, we’re on the cusp of finding out.

[The New York Times | The Washington Post]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember the immortal words of Tom Petty: the waiting is the hardest part.