Every Monday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, trying to maintain perspective…

DEEP IMPACT

On Wednesday—the day between the extended trash-incineration known as the first US presidential debate and the White House’s announcement that Donald and Melania Trump had tested positive for COVID-19—the Bureau of Labor Statistics released the last US jobs report before the November election. The Washington Post teased out many of the harrowing realities lurking in the data. It makes clear that, even while much of the art industry, myself included, habitually refreshes their news source of choice for updates on the president’s health, the damage done to artists and arts workers during the Trump administration will outlast him, even if he ultimately makes a full recovery from the virus.

In short, we now have data from an independent government body confirming on a macro level what we in the walled garden of the arts have been hearing from industry-specific surveys and reporting for months: the pandemic recession has been—and will continue to be—the cruelest to the most vulnerable American workers, including the creative class.

The most direct impact on the arts economy is visible in the following takeaway from the Post:

Nine of the 10 hardest-hit industries in the coronavirus recession are services. They include performing arts, sightseeing, hotels, transportation, clothing retail, and museums. Economists worry that many of these jobs will not return, with restaurants and entertainment venues going out of business.

These findings deliver a doubly vicious blow to the arts sector. First, as the excerpt above makes plain, the initial damage lands squarely on workers in the American art industry. But the second blow is subtler. It primarily concerns artists and the work they do in other industries to support their moonlit studio practice in hopes that one day their artwork will become their primary income source (and a sustainable one at that).

What is the scale of the problem faced by artists with day jobs, then? It’s difficult to quantify, but we have at least some data to ground us—and the numbers aren’t pretty.

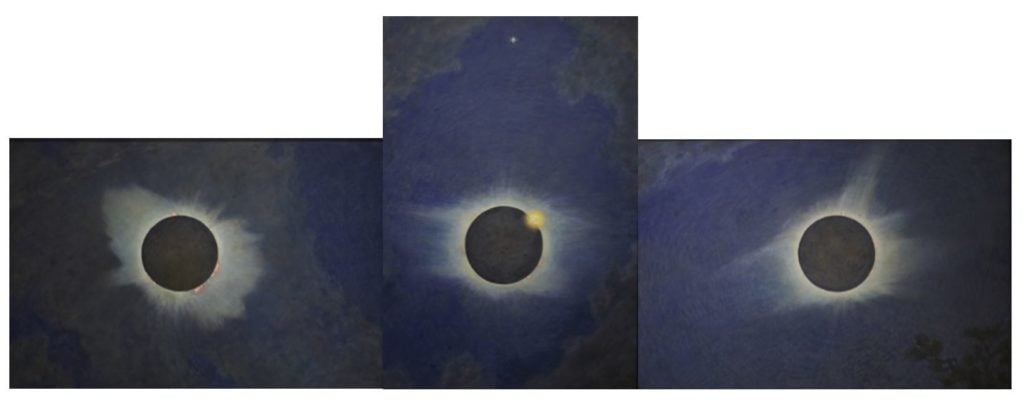

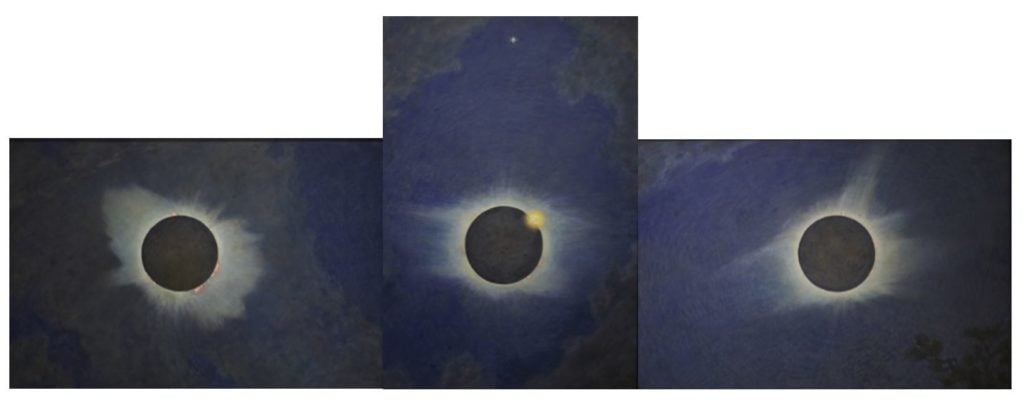

Howard Russell Butler’s Triptych eclipses left to right 1918. 1923, 1925. Courtesy of Princeton University.

MISFORTUNE BY MOONLIGHT

According to research by the National Endowment for the Arts in 2013, about 271,000 Americans listed “artist” as their secondary occupation. (For clarity, the NEA’s definition of “artist” encompasses everything from fine artists and photographers, to producers and directors, to architects and designers.) Among the Americans moonlighting as artists, just shy of 30 percent held their main job in leisure and hospitality, retail and wholesale, or other services that would fall into the consortium of industries that the Bureau of Labor Statistics says has been punched square in the mouth by the pandemic.

However, that 30 percent statistic is misleadingly low for two reasons. The first is that another 30 percent of moonlighting artists earned their main revenue stream by working in what the NEA called “educational and health services.” The organization doesn’t break down in depth what kinds of jobs constitute these subcategories (at least in the online data), but one example provided is “teachers at music and dance schools.” So it stands to reason that “educational and health services” might also encompass positions at museums and other arts nonprofits—in which case the shutdown is preying on the main income sources of significantly more than that initial 30 percent of artists spending their days working in leisure, hospitality, and sales.

The second reason to upgrade our estimate is that it took several years beyond 2013 for US employment to finish healing (to the extent it ever did) from the 2008 recession, and the economy did so by adding millions more positions in the service sector. Of the 22.5 million US jobs gained from 2010 until the arrival of COVID-19 in 2020, the Washington Post reports that 18.9 million (84 percent) were service jobs, with the highest proportion being in restaurants and bars.

Obviously, restaurants and bars offer both relatively low wages and low odds of maintaining their staffing levels during a widespread public-health crisis. We don’t know how many more striving artists started stringing together a meager living as servers, bartenders, line cooks, and other under-appreciated food-and-beverage workers between 2013 and this March, but I think it’s safe to estimate that we’re talking about tens of thousands more than were captured in the NEA’s data seven years ago.

US President Donald Trump makes his way to board Air Force One. Photo by MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images.

DEEP, DARK WELL

I’m sorry to say the news gets even worse if you keep digging. From a macro perspective, economist Justin Wolfers points out that the nation is still 11 million jobs shy of the number it supported in February 2020—and that this is “a larger gap than at the low point of the [2008–9] financial crisis.” Sadly, though not surprisingly, the US’s anemic economic recovery has been unequally distributed, too. Here’s the Post again:

While the nation overall has regained nearly half of the lost jobs, several key demographic groups have recovered more slowly, including mothers of school-age children, Black men, Black women, Hispanic men, Asian Americans, younger Americans (ages 25 to 34), and people without college degrees.

To chisel deeper into just one of these cruel imbalances, roughly 865,000 American women entirely abandoned the search for work between February and September, with many of them doing so to take on childcare duties in a distressed family situation. Their withdrawal from the labor quest means they are no longer counted as “unemployed” at all, a fatal flaw in the Bureau of Labor Statistics’s statement that unemployment “improved” to 7.9 percent last month.

Overall, then, the jobs figures don’t just tell us that a huge number of American artists may have to relinquish their studio time to a desperate search for new day jobs in a horrific recession; they also tell us that the ones who can continue making artwork will be overwhelmingly white and male. So the data leads to the same conclusion as the increasingly apocalyptic environmental scenario I wrote about two weeks ago: conditions in the wider economy are conspiring to make the US’s already diversity-bereft art industry even less representative of the country’s population from the standpoints of ethnicity, gender, and class than it already is.

It would be naive to place the blame for this grim calculus entirely on the Trump administration. Some of these trends have been slowly but steadily driving the US’s creative economy toward the abyss since the late 1970s. That said, Wolfers claims that the country currently supports nearly four million fewer jobs than it did in January 2017—and that, while the virus is a “major” factor here, “results in other countries suggest it didn’t have to be this bad” in the labor market.

I filed this column on Saturday night, just over 24 hours after we first heard Trump had been given an experimental drug cocktail “as a precautionary measure” and transported to Walter Reed Medical Center. There’s no telling where the saga of his health will have taken us by the time you read this. But the point is that his administration has already mangled the arts sector in ways it could least afford, and it will require years of sustained, radical action if we ever hope to reverse the damage. No matter what his fate in this latest surreal episode of our hallucinatory year, that shameful legacy is already secure.

[The Washington Post]

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: despite the old saying that “what goes around comes around,” sometimes it just keeps going.