Opinion

What Painter Jon McNaughton’s New Patriotic-Religious Fantasia of Donald Trump Actually Means

Who's the guy with the flowy hair?

Who's the guy with the flowy hair?

Ben Davis

Someday, and one hopes someday soon, Donald Trump will no longer be in office. When and if he voluntarily vacates the White House for whatever post-presidency trouble he can stir up, one of his final symbolic duties will be to commission a portrait of himself. No artist has been auditioning harder for that role than Jon McNaughton.

Plenty has been written about McNaughton in the last decade. Based in Provo, Utah, he’s an artist known for a Norman Rockwell-meets-Pepe the Frog style of figurative painting: canvasses where historical figures and beaming Christs meet in stiff tableaux, usually over-the-top allegories bringing some Fox News talking point to life. You may know him for his 2010 painting The Forgotten Man, which depicted Barack Obama turning his back on a forlorn Average Joe and stomping on the US Constitution as a crowd of all the presidents who came before looks on in dismay. Sean Hannity purchased the painting in 2016.

McNaughton’s latest, released last week, is titled Legacy of Hope. The picture is inspired by a February 27 photo that the White House released of Black supporters surrounding Trump, laying hands on him to pray. In introducing the new opus, the artist wrote of being in despair about the state of the world and finding comfort in the image. He recreated the scene—only this time, as is his wont, with historical figures surrounding Trump, adding in the US Constitution laid out before him between the Bible and the Keys to the Kingdom.

I was feeling discouraged about the world in which we live—until the @whitehouse released an INSPIRATIONAL photo of Black religious and political leaders—HEROES—praying for @POTUS and the #USA — it made me think about America's legacy of hope! @realDonaldTrump pic.twitter.com/cPtonkEfgD

— Jon McNaughton (@McNaughtonArt) July 24, 2020

Like the late Thomas Kinkade, McNaughton has a fanbase outside the ordinary art scene, and he’s pitching mass appeal. On his website, Legacy of Hope is available in tiered editions. You can get a lithograph for $29. Editions in the $204, $340, and $750 range are listed as sold out. The original is available for $27,000 (meaning his prices have come down considerably from the onetime $300,000 asking price for The Forgotten Man).

Why write about it? Well, I’m not going to pretend like it is not fun to pick apart something so goony. But at the same time, the painting actually does say something about how a certain conservative culture-warrior mindset is digesting the present debates about history and representation. Or failing to digest them. Legacy of Hope actually might be the aesthetic equivalent of indigestion.

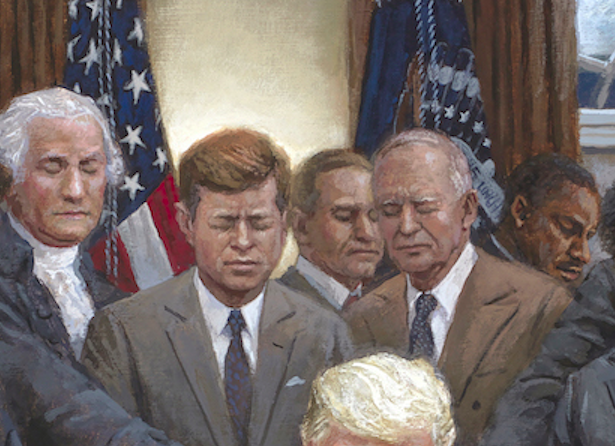

Most of the figures surrounding POTUS are easily identifiable. It’s no surprise that Reagan takes up the most space, given his iconic status for modern American conservatism, or that the major Founding Fathers make appearances (even if McNaughton is not a good enough painter to quite nail their likeness).

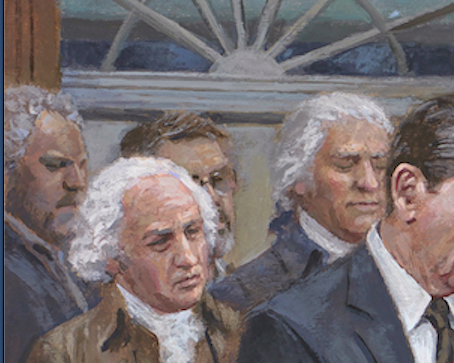

Detail of Jon McNaughton’s Legacy of Hope, with Calvin Coolidge at center.

Lincoln and JFK have prominent places. You might be surprised to learn that the figure who appears at dead center behind Trump is Calvin Coolidge.

For a Trump superfan, this central place for “Silent Cal” makes sense: the 1920s Republican was known for coining the term “law and order,” for his hard-line immigration policy that inspired both Hitler and Trump adviser Steven Miller, and for a Fourth of July speech he once gave that “puts the Cool in Coolidge,” according to Fox News.

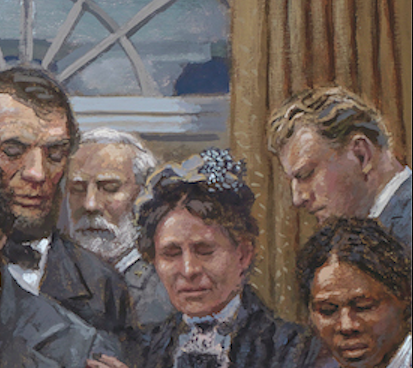

Detail of Jon NocNaughton’s Legacy of Hope, with Robert E. Lee at standing behind Abraham Lincoln, at center.

It seems a deliberate provocation to place Robert E. Lee, the Confederate commander, on a level with Martin Luther King, Jr., clustered with Lincoln and abolitionist Frederick Douglass.

The white lady is tough to identify, but I’m guessing that it’s Dolley Madison (after first leaning toward Susan B. Anthony). She is remembered for saving a Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington during the 1814 Burning of Washington—making her symbolically useful in this statue-toppling time. [Update: a Facebook friend guesses that it’s Clara Barton. I think that might be right!]

But the most difficult figures to identity are at the margins.

Detail of the right side of Jon McNaughton’s Legacy of Hope.

On one side, you have two less readily identifiable faces. The one who is coyly obscured by Madison’s head is, I believe, a self-portrait of McNaughton himself.

Painter Jon McNaughton shows off a portrait of President Reagan at a taping of Sean Hannity’s Fox News TV show. Photo by Zach D Roberts/NurPhoto via Getty Images.

The other figure, the one who would literally be at Trump’s extreme right, so to speak, is almost certainly Andrew Breitbart, the ultra-reactionary media provocateur whose namesake news service helped propel Trump into office.

I miss Andrew Breitbart. My painting titled "No Fear." pic.twitter.com/LaFLU3m6zr

— Jon McNaughton (@McNaughtonArt) June 24, 2020

That leaves the strapping man with the swept back hair at the other edge of the painting as the main mystery.

Detail of the left side of Jon McNaughton’s Legacy of Hope.

Here we have a debate! My mom is sure it’s “pastor to presidents” Billy Graham—which makes sense in this gallery, given the focus on Trump’s divine calling. It wouldn’t be the first tribute to Graham in McNaughton’s oeuvre, and Graham’s likeness is set for Trump’s Garden of American Heroes.

My first guess was a young John Wayne, the cowboy actor whom McNaughton tweets about often. Wayne’s name has been in the news once again after social media rediscovered his notorious pro-“white supremacy” Playboy interview from 1971—leading to calls to rechristen John Wayne Airport in Orange County. Wayne makes sense as a guess given the figure’s place near Robert E. Lee, whose image is also being toppled everywhere.

I wish he were here today. My sketch of John Wayne. pic.twitter.com/CnCUHjxVBL

— Jon McNaughton (@McNaughtonArt) June 28, 2020

In any case, what to make of this historical hodgepodge?

The most basic point about McNaughton’s paintings is always that they are mediocre paintings. (Take a moment to really look at Donald Trump’s hands in this painting—they look like someone tried to make an Edible Arrangement out of hot dogs.) They are, however, highly functional memes. Like Trump or Breitbart, McNaughton has mastered the art of leveraging outrage and mockery directed at him to expand his reach.

Detail of Trump hands in Jon McNaughton’s Legacy of Hope.

In one sense, he owes his reputation to Rachel Maddow, who in 2012 gave McNaughton a big boost when her blog turned his then-obscure The Forgotten Man, painted two years before, into “caption contest” fodder, asking viewers to spot “historical inaccuracies.” This caused, McNaughton claims, a “100 fold” spike in sales.

Legacy of Hope has caused a similar, if smaller, tizzy, with people online riffing on its incongruities.

It's always a pleasure to do a painting that triggers the left while supporting the President. Bullseye!https://t.co/tmgaJvoK16

— Jon McNaughton (@McNaughtonArt) July 27, 2020

But I actually do give McNaughton credit for being marginally more sincere than that. I think there are people who like this style of art merely because it “triggers the libs,” and then also people who really just like it.

The blunt-force symbolism, stiff theatricality, “loose realism,” and blithe historical anomalies are all actually pretty typical of a certain kind of illustrational painting typified by someone like 20th-century religious artist Harry Anderson. Just consider Anderson’s Divine Councilor, showing Christ working as a business coach, or his famous Prince of Peace, depicting a King Kong-sized Jesus knocking on the United Nations building.

McNaughton filters Fox News talking points through that aesthetic lingo. Since there are a good number of conservative religious people who are also fervent Trump Republicans, that works as a nice formula for a lot of people—sincerely.

At any rate, I think there’s no reason to talk about Legacy of Hope if you think it’s merely a gag or a troll. It represents a poisonous viewpoint—but it is a real and popular viewpoint that the people to whom McNaughton is marketing his art actually hold, not just an attempt to get the liberals’ goat.

Legacy of Hope was inspired by a picture of Black Trump fans. As a work, its most obvious novelty is incorporating the non-office-holding Black political icons of Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and MLK into the bog-standard “pantheon of American presidents” rooting for Trump—new terrain for McNaughton, I think, showing how even he is reshaping his MO to respond to current debates about how US history gets told.

In a video accompanying Legacy of Hope, McNaughton channels Donald Trump’s July 4 Mount Rushmore speech, speaks about how the liberal media is cheering on the destruction of the nation’s heritage, and consciously places his artwork as a reply to the New York Times’s “1619 Project,” which analyzes how the legacy of slavery has deformed the nation:

Contrary to what some might tell you, the United States didn’t begin in 1619 with the first importation of slaves. The United States has a specific birth date. It began in 1776. It began when we not only declared our independence to the system that introduced slavery to the New World. But our country also began when we declared that ‘all men and women are created equal.’ From that day forward, great men and women, people like George Washington, Harriet Tubman, Abraham Lincoln, Thomas Jefferson, and Frederick Douglass have risen up and have fought and died to insure that this nation lives up to its founding creed. This is America. A legacy of hope.

You’ve gotta be in awe at the freakish logic of a painting that presents not just Lincoln, but Robert E. Lee, the commander of the Confederacy, as an avatar of the highest ideals of the United States.

I guess it’s a reminder that even those inhabiting the deep end of the Breitbart-loving, Fox-watching conservative cultural space cherish an idea of themselves as not being motivated by racism. In their own heads, they are fair-minded speakers of unpopular truths, opposing deranged liberals imposing their one-sided negative reading on cherished symbols.

Legacy of Hope‘s incongruous congery of figures isn’t only outrage bait; its jumble quality is a functional part of its symbolism. Whatever your view of these individual history-book figures and their human failings, it says, they were all just bit players in God’s Plan for the United States—and that’s the important thing. Much the way Trump may act like a godless sociopath, but he’s actually doing the Lord’s work.

This view makes a virtue of militant indifference to the darker side of US history. George Washington is preserved as a prayerful version of the familiar image from the dollar bill—rather than the guy who literally made dentures from his own slaves’ teeth, a fact that’s led even Mount Vernon to reconsider how it presents the first president.

This righteous narrative’s evacuation of history has the reverse effect too: MLK or Tubman can enter the pantheon next to the Founders—as long as they are rendered as uncontroversial icons of “hope,” without too much questioning of how their legacy might disturb any of the other heroic myths about the nation.

I’d go on, but Frederick Douglass’s own famous July 4th oration, the 1852 “What to the Slave Is July 4th?”, is pretty much as direct a reply to this kind of pretend-innocent national myth-making as is possible:

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer; a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sound of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciation of tyrants brass fronted impudence; your shout of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanks-givings, with all your religious parade and solemnity, are to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices more shocking and bloody than are the people of the United States, at this very hour.

I can’t tell you for sure who Swept-Back-Hair Guy is. I can say with confidence that Frederick Douglass would not have liked Legacy of Hope.